The Puzzling Assassination of Martin Peel in Millville and

the President Threatens Martial Law

In the early 1880s Tombstone and nearby areas were plagued with violence (Walker, 1969). The Texas Rangers to the east and the growth of orderly communities in California to the west induced criminals to move into Arizona. Cochise County then probably had a population of only approximately 9560 people, with more than 85% of them concentrated in Tombstone and the towns of Charleston, Millville, Contention City, and Fairbank. The scattered distribution of people in other areas meant that outlaws could easily move about in many places without being observed. The sudden silver boom centered around Tombstone attracted a variety of undesirable elements. There were many opportunities for making ill-gotten gains. Stagecoaches regularly moved silver bullion from Tombstone to the railroad at Benson. Merchants and bankers of Tombstone had to send out money to settle their accounts. Because horses were the chief means of transportation, they were always in demand, and there was a ready market for stolen horses. There was also substantial demand for beef because of the needs of the army and of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The county was an excellent place for illegal operations. Law abiding citizens were so occupied with making money that they often had little time to devote to other affairs. The boundaries of four different jurisdictions came together near the southeastern corner of the county, Arizona, New Mexico, and the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora. Outlaws could easily evade pursuit by riding from one jurisdiction to another. People were heavily armed because of the threat of Apache attacks. The lawless men who rustled livestock or held up stages for a living were commonly called “cowboys.” This faction was so strong that ranchers often had to cooperate with them or lose their own stock. Civilian authorities were often corrupt or incompetent or simply lacked adequate resources for enforcing the law.

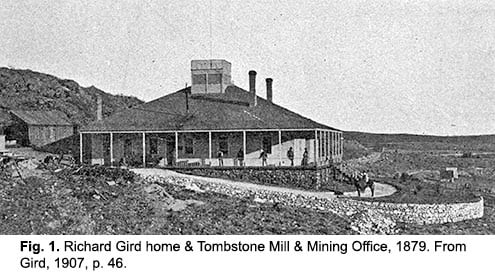

Many killings received only slight mention in newspapers. However, the assassination of Martin Reuter Peel on March 25, 1882 horrified many people and received considerable press attention in Tombstone and elsewhere. His assassination took place in the office of the building (Fig. 1) that Richard Gird had constructed in Millville to house himself and his wife and the office of the Tombstone Mill & Mining Company (TWE, 1882b). Millville then had the two mills of the company, the building with an office and the living quarters for Gird and his wife, a boardinghouse, stables, and other buildings and was essentially a small village opposite the larger settlement of Charleston where most mill workers lived.

Many killings received only slight mention in newspapers. However, the assassination of Martin Reuter Peel on March 25, 1882 horrified many people and received considerable press attention in Tombstone and elsewhere. His assassination took place in the office of the building (Fig. 1) that Richard Gird had constructed in Millville to house himself and his wife and the office of the Tombstone Mill & Mining Company (TWE, 1882b). Millville then had the two mills of the company, the building with an office and the living quarters for Gird and his wife, a boardinghouse, stables, and other buildings and was essentially a small village opposite the larger settlement of Charleston where most mill workers lived.

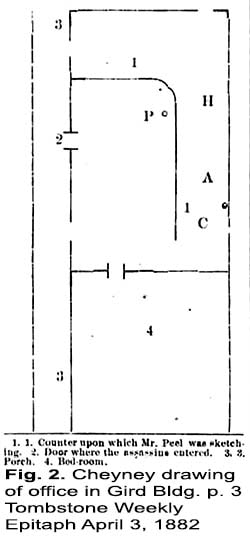

The company had a month or two previously engaged Martin Peel to help rebuild the dam on the San Pedro River that supplied its mills with water and to help with repair of the flume that carried the water. On the evening of his murder, Peel had finished his work and was relaxing together with fellow employees, W. L. Austin, George W. Cheyney, and F. F. Hunt. He was enjoying himself sketching a face while sitting on the outside of a counter that ran through the center of the office. He was thus in position “P” close to door number 2 of Fig 2. Hunt, Austin and Cheyney were behind the counter in the positions indicated by “H,” “A,” and “C” respectively.

At approximately 8:20 PM the men noticed a fumbling at the door knob of door number 2 and then a heavy rap–probably produced with the butt of a gun. Austin shouted, “Come in.” Someone then flung the door wide open, and a man with a rifle entered and was immediately followed by another who brought his rifle down as he entered. Both assailants fired a single shot almost immediately as they entered. One bullet shot Peel through the heart and because of the close range set his clothing on fire. He rose from his chair and then fell down dead. The bullet that killed Peel came from a rifle that was already in firing position when the door opened. The shot fired by the second man was apparently aimed at Austin. However, the second shot was slightly delayed after the first, possibly because the second assailant was the one who flung open the door. All three of the employees behind the counter were able to drop down behind it, and the shot that missed buried itself in the wall as shown by the lower small circle of Fig. 2. The bullet that killed Peel made a hole in the counter as indicated by the small upper circle.

Both assailants fled after having each fired a single shot. They were masked with handkerchiefs, and the only one who was well seen wore a white hat that he lost on his way to the horses that were held by an accomplice a few hundred yards from the office. Several men reported rockets fired after the assassination.

People were utterly bewildered as to the motive for the attack. The assailants did not demand money or bullion. The night was not stormy, and the apparent use of signal rockets was certainly not part of the normal routine of a robbery. Citizens wondered if the use of rockets indicated that the deed was premeditated and that the rockets were used to inform someone that the deed had been accomplished. Cheyney reported that he felt that the assailants would have had sufficient time from their departure from the office to reach the area from which it appeared that the rockets were launched.

Peel lacked enemies as far as anyone knew. This young man was the son of Judge Bryan Peel, a highly respected resident of Tombstone and was also one of the producers of a well-regarded map of the Tombstone Mining District (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 65; Ingoldsby et al., 1881.). Before moving to Tombstone, Martin Peel had lived in Los Angeles and received training there as an engineer. The Los Angeles Herald stated on March 28 (LAH, 1882a) that “We had the pleasure of knowing deceased intimately during the earlier years of our residence in Los Angeles and always found him a thorough gentleman, honorable and high-minded in all his impulses, a character which he bore amongst all who knew him. His early death casts a deep gloom over a large circle of attached relatives and friends.”

Governor Tritle authorized the Tombstone Epitaph to announce that he was offering a reward of $500 for the arrest of the murderers (TWE, 1882c). The paper duly reported the reward, suggested the County Board of Supervisors supplement it with a similar amount, and stated, “it is more than likely that they will do so at their first meeting in April.” The newspaper was indeed correct, and the County Board of Supervisors during their April meeting TWE, 1882f). authorized Sheriff Behan to offer a reward of $500 for the capture of the murderer of Peel and also another $500 reward for the murderer of “old man McMenomy, who was killed on the San Pedro, near St. David’s, about the same time of the murder of Mr. Peel.”

Events on March 28 may have led to the capture of the assailants (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 302-311; TWE, 1882d). At about 7 PM on the evening of March 28, E. A. Harley, the deputy sheriff in charge of the office in the absence of Sheriff Behan, learned that two men for whom the office had warrants, named Billy Grounds, alias “Billy the Kid,” and Zwing Hunt, would be near Tombstone during that night or early in the next morning. (Zwing Hunt was not related to F. F. Hunt.) The two men had gone to the Chandler milk ranch approximately nine or ten miles east of Tombstone and found that the only person there was a man in charge because the owner was in Tombstone. Two Mexican families lived in a house about 100 yards away from the main ranch house. Hunt and Grounds said that the owner of the ranch owned them $75 and sent a note to the owner in Tombstone by the man in charge. The note asked the owner to send them the money by bearer because they were getting ready to leave the country. The owner instead informed the sheriff’s office of the outlaw’s location. In the meantime, Bull Lewis, a teamster, came to the ranch and was the only person in the house with the outlaws when the posse arrived. A. Harley ordered Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge to organize a posse and to leave town about 1:00 or 2:00 AM so as to be in the proper area to arrest the outlaws. The office arranged for two miners, Jack Young and John A. Gillespie, and a jail guard named E. H. Allen to be members of the posse.

The posse arrived at the ranch just before dawn, tied up their horses a distance from the house, and crept toward it. Breakenridge placed Young and Gillespie at the back door behind a woodpile and told them to be quiet until daylight when he expected that the outlaws would come outside to look for their horses. Allen and Breakenridge went to the front of the house where there was both a window and a door. Just as they arrived there, Gillespie knocked on the rear door and when asked who was there replied, “It is me, the sheriff.”

The two outlaws opened the door and shot Gillespie dead and also shot Young in the thigh. The front door then opened and Bull Lewis ran out shouting, “Don’t shoot, I am innocent.” A shot from the front door creased Allen across the neck, knocking him senseless. Breakenridge heard someone step toward the door from the inside and grabbed Allen by his collar and dragged him down the bank of a dry creek in front of the house. Breakenridge jumped behind a small tree just as someone shot from the front door, and the bullet hit the tree. The person who fired the shot stepped to the door to fire another, and Breakenridge fired one barrel of his shotgun, loaded with buckshot, into the opening. The buckshot hit Grounds in the face, and he fell to the ground. Meanwhile Allen had regained consciousness. Hunt came around from the back of the house calling out, “Billy, Billy.”

Both Breakenridge and Allen fired at Hunt, and he disappeared, and they thought that he had been shot. Young called out that he had been shot, and Breakenridge ran to him and helped him get to another house about 100 yards from the main ranch house. Allen laid behind the creek bank and guarded the front door so that no one could come out and shoot Breakenridge. All of the shots up to that point had been within a period of two minutes.

Breakenridge took Young to a place where he could have attention once a doctor arrived and returned to Allen, told him to guard the house, said that he thought Hunt was wounded, and that he would go up the creek to look for him. By then it was daylight, and the two men could see the feet of Billy Grounds sticking just out of the door.

Breakenridge walked about 100 yards up the creek when he heard the bear grass rustle and aimed his gun at the area and shouted, “Throw up your hands.” Zwing Hunt immediately raised his hands, and Breakenridge ordered him to lie down and put his hands in front of him. After Hunt did that, Breakenridge sent Allen to get a milk wagon that was at the other house and to get the men there to help take Hunt to that house. The outlaw was shot through the left lung, and every time he breathed, air whistled out the wound in his back where the bullet exited. Breakenridge took off his coat and made a pillow with it for Hunt, and when Allen and the other men arrived with the milk wagon took Hunt to the house. He sent Bull Lewis to Tombstone with a message asking for an ambulance and the doctor. The posse found Gillespie dead at the back door, and Grounds still alive, although he never recovered consciousness. The posse put the outlaws on a mattress, made a fire, put hot water bottles at their feet, and did what they could to make them comfortable.

The doctor eventually arrived with a crowd that included several friends of Breakenridge because people had gotten the belief that he had been killed. The men returned to Tombstone with Gillespie dead in one wagon, the badly wounded Grounds and Hunt in another, Allen and Young in the ambulance, and Breakenridge–the only posse member not shot–riding on a horse. Young told Breakenridge that Gillespie had wanted to run for sheriff in the next election and decided to make the arrest alone and thereby get credit for it. Hunt said that he thought a posse led by Earp was after them and would not have fought had he known otherwise.

People began to suspect that Grounds and Zwing Hunt were the assassins or accessories to the murder (Parsons, 1996, p. 215). The warrants upon which the posse acted were only for charges of rustling, and it seemed improbable that the rustlers would’ve resisted to the point of death (LAH, 1882b). Moreover, one of the rustlers wore a hat that was much too large for him, and one of the assassins had lost a hat near the scene of the assassination. Shortly after the shooting, Hunt told Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge that he had come to the place with the intention of “downing” Jack Chandler who he said owed him money (AWC, 1882b). Hunt then asked what the charges were against him and seemed very relieved when the deputy sheriff replied “Grand larceny.” His evident relief resulted in the suspicion that he and Grounds were involved in the assassination. At some point the horses of the two outlaws were put into Dunbar’s corral in Tombstone, and the boots of the men were confiscated as potential evidence. The possible involvement of the two outlaws was examined during the lengthy Coroner’s inquest that started on March 27.

The first witness during the inquest was George W. Cheyney, a clerk, who described the details of the assassination as given above and drew the diagram of Fig. 2 (TWE, 1882b). Cheyney added that after the killing he and Austin and Hunt armed themselves, went out onto the porch and then walked along the road several hundred yards where they met the watchman who was coming down the hill. They sent him to rouse additional men, and within five or six minutes several men had collected and divided into parties that went around the house to the office door. Cheyney found that Peel was lying on his back with his head and shoulders on the porch and had no pulse. He found that the victim’s clothing was on fire and together with other men carried him into a chamber adjoining the office. Cheyney was not looking at Peel at the time the assassins came in and could not say whether or not weapons were pointed at him in particular but reported that the rifles were leveled when the men came in. He knew of no enemies of Peel, had no idea why the deed was done, and speculated that the object might have been robbery. He saw two rockets shortly after the shooting on a line between Charleston and Tombstone and noted that some of the other men reported seeing the rockets themselves.

F. F. Hunt, an assayer, next testified that he agreed with Cheyney’s testimony, knew of no personal feeling or cause for the attack, felt robbery was the only reason he could think of, stated that he did not know how much bullion was in the vault in the office, and reported that he did not know of any money in the vault.

Miss Mary Melane then stated that she was the housekeeper in the building and heard everything distinctly in her room that was right over the office. Contrary to what other witnesses said, she reported hearing Peel cry “Oh!” and recognized his voice. She knew of nothing of a personal nature that would have led to the incident.

WM. H. Dugan, a laborer, testified that at about 8 PM he was working wheeling in “tailings,” about 150 yards from the company office and heard what sounded like two shots. He saw two or three objects rapidly pass by the farther end of the office and go towards an adjacent woodpile. He saw several flashes before the shots and afterwards saw a rocket in an approximately eastern direction. He never heard anyone speaking of the victim with anything but respect.

George Fraser, an engineer in the Gird mill, was in his house at Charleston at about 8 PM when the watchman came to the door and told him to arm himself and go to the office as fast as possible because there had been an attack. He did not see or hear the shooting but did report observing several flashes and found the bullet that had killed Peel in a pigeonhole about three inches from the top of the counter.

Henry Nelson, a melter for the company, did not see any suspicious circumstances before the shooting but saw flashes afterwards in an easterly direction and then saw one in a northerly direction. He picked up a hat that was lying in front of the office door and stated that he believed that the hat that was shown to him in court was the same one that he had found. Nelson reported that there was no evidence of a thunderstorm and nothing to indicate lightning.

On the second day of the inquest (TWE, 1882c), E. T. Hardy, a Bisbee merchant, stated that he did not remember selling either the hat or handkerchief that were shown to him in court. For reasons that are not given in the newspaper article about the inquest, Hardy testified that he knew a man named Henry and last saw him it Bisbee approximately four or five days previously. Hardy met him on the road about 10 days previously and noted that he was armed with a gun and six-shooter and said he was shooting rabbits. Probably there was speculation that Henry was involved in the murder.

Henry Raymond testified next and said that he lived in Tombstone but had been living in Bisbee until the night before the murder. He left Lewis Spring about 10 AM on the day of the murder (Saturday), passed through Charleston, went about a quarter of a mile from the Boston Mill and stayed there until 4 PM. He then continued on to Tombstone, stopping about an hour to hunt rabbits. He saw no one on the road except some men blasting rock below Charleston on the river and three men sitting beside the road. Raymond reported that he never wore a white hat, never saw Judge Peel before outside of Tombstone, did not recognize Austin, saw no lightning, bought his hat and boots from Glover approximately a week before Christmas, and did not buy any handkerchiefs from the merchant when he bought the hat and boots. Raymond then contradicted himself by stating that it was 12 o’clock on Friday when he met the men below Charleston and that he had arrived in town Friday night and was in Tombstone all of the day of the murder.

W. L. Austin, mill manager, corroborated Cheney’s testimony and testified that he had a revolver near him and grabbed for it. He thought that Peel made the same move and that that was the cause of the shot. Austin dropped and thus escaped the shot that was fired at him. He subsequently examined the tracks made by the assailants and concluded that one of them had boots that were about medium-size while the other had somewhat peculiar boots. The boot prints of one assailant were 9 ½ inches long and 3 ½ inches wide and had tread on the side. The other assassin made larger tracks, with a hollow in each heel. One of the horses was large and had been recently shod and must have been a draft animal because of the type of its shoe. The tracks of the assailants headed in the same direction as where he saw the flashes.

There were only two witnesses on the third day of the inquest (TWE, 1882d). J. A. Nolly, a carpenter and miner residing in Charleston, stated that about two minutes after the noon whistle blew on the day of the murder he saw Henry Raymond. Henry had a gun and pistol and wore a light drab hat that was lighter in color than the hat that Nolly found near the mill office. Isaac Jacobs stated that Henry Raymond began working for him on March 26 and that he bought some rabbits from him the day before. He last saw Raymond at about dusk the night of the murder.

The fourth day of the inquest included testimony from three witnesses (TWE, 1882e). T. J. Harrison, a resident of Charleston, stated that the hat shown in court looked like one that he used to wear. He was not positive if it was the one, but thought it was. He obtained the hat from Fin Clanton approximately last December, and Clanton had said that he obtained it from Mr. Ayres, a saloon keeper in Charleston.

Edward Overton said that he lived about six miles below Charleston, at Lewis Springs. At noon on Sunday, the day after the killing, two young men came by on horseback and asked for food, stating that they had not eaten since the previous morning. He fed them, and they laid down to rest. Company C of soldiers later came by. Overton told the young men that there were soldiers in the area, and they became “very much excited,” talked together in low tones in the corner of the house away from him, and afterwards stated that they did not want to be seen by anyone. Overton told the men that the soldiers were not looking for them but rather for Indians. The men remained with him until about five minutes before sunrise on Monday morning, were afraid while there, and told Overton that they were escaping from justice. Overton subsequently visited the hospital and reported that the men there who had been shot were the ones who stayed with him. One of the men recognized him and said he wished they had stayed at his house. One of the men asked two or three times if Overton had heard about anyone being killed at Charleston lately and seemed very relieved when Overton said no because he did not learn about the murder of Peel until later. Overton saw the horses at Dunbar’s corral that were said to have been taken from the men and recognized them as the ones they had ridden away from his house.

Austin testified that he had examined the boots of Grounds and Zwing Hunt and that the tracks he saw at the mill might have been made by them. However, he stated that he could not swear to that although he was “quite positive in my own mind that they are the ones.” He stated that he had examined the horses at the corral taken from Grounds and Hunt and that one of the hoofs corresponded very nearly to one of the tracks that had been made at the mill, but that he did not recognize the other horse. He suggested that three other persons, Henry Fishback, McClure, and a carpenter could better identify the horses and boots then he could. Austin had examined the guns that the sheriff had in his charge but could not identify them.

The inquest concluded on April 3, the fifth day of the inquest (TWE, 1882a). Henry Fishback, a resident of Charleston and an amalgamator for the Tombstone M. & M. Co., testified that he had examined the tracks of the assassins the morning after the shooting and thought that he could recognize the boots that made them. One was made by a heavy boot, and the other looked as though it had been made by a "fine one.” The coroner produced the boots from Grounds and Hunt, and the witness stated that one of the pair might be those that made the tracks but that he was not sure. He had examined the horses at the corral and thought that the larger of them might’ve made one of the sets of tracks that were at the mill but did not think that the other horse could’ve made the other set of tracks.

Ernst McClure, a Charleston merchant, examined the boots and stated that a pair of them might have produced the tracks at the mill. He also thought that one of the horses at the stable could’ve made the tracks at the murder site.

J. E. Smith, a carpenter in Charleston, examined the tracks at the mill and concluded that none of the boots made them. He thought that one of the horses in Dunbar’s corral might have made one of the set of tracks but remarked that he was not an expert trailer of either man or stock.

D. H. Holt examined the hat that Cheney had given him the night after the shooting. Another man in Charleston had one just like it and said that he got it at McKean & Knights.

Dr. H. M. Matthews testified about the wound that killed Peel. It was made by a ball that passed through his right side and through the heart, killing him instantly.

The inquest then recessed from 12:30 until 1 PM. The jury convened again at 1:30 PM and after deliberation concluded that the victim’s name was M. R. Peel, aged about 26, a native of Texas, and that he died on the night of March 25 at the office of Tombstone M. & M. Co. mills from a gunshot wound “inflicted by parties unknown to the jury.” The evidence possibly implicating Hunt and Grounds and the often uncertain or conflicting conclusions of witnesses simply did not provide strong enough proof to conclude that the rustlers had been responsible for the assassination.

Any hope of obtaining information from Zwing Hunt or of prosecuting him at least on the rustling charges literally vanished on the night of April 27 between 8 and 9 PM (TWE, 1882g). Authorities had deposited him in the county hospital to recuperate. On Monday, April 24 supervisor Tasker had spoken with Supervisor Joyce about removing the outlaw to the jail. However, the latter supervisor felt that Hunt was still in such a serious condition that a transfer would endanger his life, and that there was no current danger of the man escaping. The doctor treating him, Dr. Goodfellow, said that the man’s condition was so critical that he would have opposed such a move as cruel and liable to kill Hunt. He also opposed moving the patient to a place that would be more comfortable than the jail because even that transfer would endanger his life.

Meanwhile Hugh Hunt the brother of Zwing had arrived in Tombstone on Sunday April 23. The brother and the father of both men were respectable merchants in Texas and reportedly “well off.” After his brother arrived, Zwing Hunt was in very good spirits and seemed to be quickly improving in health. In the last week of April, the Tombstone Epitaph had contained a communication warning of the possibility of an attempt being made to rescue the prisoner from the hospital, but a guard was not posted to prevent his escape.

Someone apparently took Zwing Hunt out of the hospital between 8 and 9 PM on April 27 and drove him away in some sort of a conveyance, the patient still apparently being too weak to have left on his own. When Hunt disappeared, there was no one in the front room with him, but there were two patients in an adjoining backroom and three or four convalescent patients sitting beneath an awning in the rear of the building. All of them said that they heard nothing and did not know about the disappearance until a few minutes before 9 PM when the janitor went into the front room and found that Hunt was gone. A messenger was immediately sent to tell Dr. Goodfellow, who immediately informed the sheriff.

Hugh Hunt returned briefly to Tombstone on June 9, 1882 and reported the details of his brother’s death (TWE, 1882h). He also claimed the horse and guns that belonged to Zwing at the time of his arrest (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 312-313). After he and his brother escaped from the hospital, they rode to the Dragoon Mountains on horseback and reached there at night. Zwing was sick and very weak and vomited several times during the journey and refused to go any further after they reached the Dragoons. Their original plan had been to continue on until they reached the Chiricahua Mountains that would provide better opportunities for hiding from the law. They rested the next day in the Dragoons and then at night rode towards the Chiricahuas. Zwing recovered rapidly, and the brothers spent all of May wandering through the Chiricahuas. On May 30 they camped in Pinery Canyon. The next morning Zwing baked bread, and Hugh made coffee and broiled some meat. The men had just started to eat breakfast when a volley of gunshot was fired toward them. Hugh at first thought that the shots were from the sheriff’s posse, but when he looked quickly around saw several Indians nearby taking aim with their rifles. Zwing pulled out his gun and cried “damn it! go to shooting.” It was the last he ever spoke because the Indians shot him four times, once in the left hip, once in the abdomen, and twice in the head. After his brother died, Hugh ran into the heavy timber and headed for their horses that were hobbled nearby. The Indians, who were on foot, ran after him and kept up a continuous firing. He jumped on a horse bareback without removing the hobbles and rode for about half a mile until he felt it was safe to remove the hobbles. Hugh reported that his brother had several times told him that he thought the posse at the Chandler ranch was the Earps and that was why he fought. A sheriff’s posse subsequently dug up the body and identified it and found that the wound in Hunt’s lung was still not healed (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 312).

On June 9, 1882 a Cochise County grand jury that had been impaneled to in part investigate the operation of the county reported that at the request of the Court it had made a “very searching” inquiry into the escape of Zwing Hunt from the County Hospital (AWC, 1882e). The jury concluded that, “his escape was owing to negligence of the Sheriff. We are of the opinion that this officer entirely and inexcusably neglected to take any measures to prevent his escape or abduction.”

The bold killing of a well-respected young man in the office of Richard Gird caused considerable consternation among residents of Tombstone. George Parsons, a well-respected resident, wrote about the incident in his diary on March 26 (Parsons, 1996, p. 214-215). “Another murder and this time of the most startling nature. Poor Peel was shot and instantly killed by two masked men at the T. M. & M. Co’s office, Charleston, last evening between eight and nine o’clock. No reason whatever assigned for the cause. Possibly an attempt at theft and perhaps simply thirst for gore on account of attitude of the company against the outlaw element. Now that it has come to killing of upright, respectable, thoroughly law abiding citizens–all are aroused and the question is now, who is next.”

The assassination of Peel, the gunfight at Chandler’s ranch that resulted in the death of a member of the posse, and the escape of Zwing were but some of the many lawless incidents in and around the San Pedro River Valley and other regions of Cochise County. The fact that Hugh Hunt felt safe returning to Tombstone after helping a prisoner escape, suggested that law enforcement was somewhat sporadic. Governor Tritle arrived in Tombstone on March 27 to investigate the violence (AWC, 1882c; Parsons, 1996, p. 214-215, 218; Wagoner, 1970, p. 194-200). He was greatly concerned by what he found and concluded that the civil authorities were powerless or unwilling to afford proper protection to life and property. He facilitated the formation of a posse to assist Deputy United States Marshall J. H. Jackson in protecting life and property and declared that when the number of the posse reached 30 he would muster them into service as a militia company. Tombstone citizens also met and discussed steps for organizing an additional military company and appointed a committee of citizens to seek donations to defray the expenses and pay the men who would assist the marshal.

The Los Angeles Herald pressured Governor Tritle to take strong action (LAH, 1882b).

There is a good deal of curiosity to know what Governor Tritle has been about all this time. In face of a crisis which has practically assumed the dimensions of an insurrection he does not seem to have thought it necessary to interpose the weight of his official authority. . . The murder of young Peel, itself following on two border tragedies, and followed in turn by two more–altogether scarcely needing 10 days for their accomplishment–will not only check the growth of Arizona and population but will actually depopulate the territory unless a remedy–a quick and sure remedy–is found for the disorders.

Tritle did take decisive action. While still in Tombstone, he telegraphed President Chester A. Arthur on March 31, described the turbulent conditions caused by the cowboys and requested a congressional appropriation of $150,000. General Sherman came to Tombstone on April 7 and was also dismayed by the violence and lawlessness.

Pressure continue to build for more action. The Arizona Weekly Citizen on April 9, 1882 (AWC, 1882c) wrote about a feeling of insecurity by citizens.

There is a general feeling of insecurity, owing to the evident powerlessness or unwillingness of the civil authorities to afford protection to life and property. The condition of affairs is insurrectionary and processes of law cannot be served without violence. A virtual reign of terror exists, which makes peaceable, law-abiding citizens unwilling to serve as posse and stifles the free expression of opinion upon the tragic occurrences of the past few weeks.

President Arthur heeded the advice of Governor Tritle and General Sherman and on April 26, 1882 sent a message to Congress stating that the governor of Arizona had reported that “violence and anarchy prevail, particularly in Cochise County and along the Mexican border.” The president stated, “Much of this disorder is caused by armed bands of desperados known as ‘Cowboys,’ by whom the depredations are not only committed within the Territory, but it is alleged predatory incursions are made therefrom into Mexico.” He requested that Congress modify an 1878 law to allow military forces to be used as a posse comitatus to help civil authorities (Arthur, 1882a). Congress responded by informing the president that he already had sufficient authority. The president responded with a proclamation on May 3, 1882 that bluntly threatened to use military forces if the lawbreakers in Arizona did not disperse (Arthur, 1882b; AWC, 1882d).

Whereas it is provided in the laws of the United States that--

Whenever, by reason of unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages of persons or rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States, it shall become impracticable, in the judgment of the President, to enforce by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings the laws of the United States within any State or Territory, it shall be lawful for the President to call forth the militia of any or all the States and to employ such parts of the land and naval forces of the United States as he may deem necessary to enforce the faithful execution of the laws of the United States or to suppress such rebellion, in whatever State or Territory thereof the laws of the United States may be forcibly opposed or the execution thereof forcibly obstructed.

And whereas it has been made to appear satisfactorily to me, by information received from the governor of the Territory of Arizona and from the General of the Army of the United States and other reliable sources, that in consequence of unlawful combinations of evil-disposed persons who are banded together to oppose and obstruct the execution of the laws it has become impracticable to enforce by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings the laws of the United States within that Territory, and that the laws of the United States have been therein forcibly opposed and the execution thereof forcibly resisted; and

Whereas the laws of the United States require that whenever it may be necessary, in the judgment of the President, to use the military forces for the purpose of enforcing the faithful execution of the laws of the United States, he shall forthwith, by proclamation, command such insurgents to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes within a limited time:

Now, therefore, I, Chester A. Arthur, President of the United States, do hereby admonish all good citizens of the United States, and especially of the Territory of Arizona, against aiding, countenancing, abetting, or taking part in any such unlawful proceedings; and I do hereby warn all persons engaged in or connected with said obstruction of the laws to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes on or before noon of the 15th day of May.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed. Done at the city of Washington, this 3d day of May, A. D. 1882, and of the Independence of the United States the one hundred and sixth. CHESTER A. ARTHUR.

Violence declined substantially after the proclamation (Tritle, 1883, p. 12). It is not clear how much that was due to the proclamation, how much was due to rustlers having been killed, how much due to ranchers and other citizens having organized for protection, and how much due to cowboys departing for more promising regions (Walker, 1969). Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge declared (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 299), “A lot of the rustlers had been killed off by the Mexicans in rustling stock and in quarrels among themselves when they were drinking. The stockmen had organized for self-protection, and the rustlers got out of the country as fast as possible.”

Literature Cited

Arthur, C. A. 1882a. To the Senate and House of Representatives. Executive Mansion, April 26, 1882, p 4688-4689. [Letter to Congress about violence in Cochise County.] In Richardson, J. D. 1897. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Prepared Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing, of the House and Senate, Pursuant to an Act of the Fifty-Second Congress of the United States. (With Additions and Encyclopedic Index by Private Enterprise). Volume X. Bureau of National Literature, Inc., New York. p. 4503-4975. (PDF accessed June 18, 2016 at https://archive.org/details/compilationofmesv10unit).

Arthur, C. A. 1882b. By the President of the united states of America. A Proclamation. May 3, 1882. Chester A. Arthur, p. 4709-4710. In Richardson, J. D. 1897. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Prepared Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing, of the House and Senate, Pursuant to an Act of the Fifty-Second Congress of the United States. (With Additions and Encyclopedic Index by Private Enterprise). Volume X. Bureau of National Literature, Inc., New York. p. 4503-4975. (PDF accessed June 18, 2016 at https://archive.org/details/compilationofmesv10unit).

AWC. 1882a. Arizona Weekly Citizen, p. 2. April 2, 1882. (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-04-02/ed-1/seq-2/).

AWC. 1882b. Arizona Weekly Citizen, p. 3. April 2, 1882. (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-04-02/ed-1/seq-3/).

AWC. 1882c. Affairs at Tombstone, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. April 9, 1882. (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-04-09/ed-1/seq-1/).

AWC. 1882d. A Proclamation. The President Wants the Cowboys to Go Home, p. 2. Arizona Weekly Citizen. May 7, 1882. (PDF accessed June 18, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-05-07/ed-1/seq-2/).

AWC. 1882e. Cochise County. Report of the Grand Jury, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. June 18, 1882. (PDF accessed June 17, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-06-18/ed-1/seq-1/).

AWE. 1882. Arizona Weekly Enterprise, p. 2. April 1, 1882. (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1882-04-01/ed-1/seq-2/).

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000b. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume Two: L-Z. Westernlore Press, Tucson. 246 p.

Breakenridge, W. M. 1992. Helldorado. Bringing the Law to the Mesquite. [Edited and with an introduction by Richard Maxwell Brown.] University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. xxxiv + 448 p.

Ingoldsby, F. S., Kelleher, M., and Peel, M. R. 1881. Map of the Tombstone Mining District. H. S. Crocker & Co., San Francisco. Scale 1200 Feet to the inch. (TIFF accessed July 9, 2014 at https://www.loc.gov/item/2012586611/).

LAH. 1882a. M. R. Peel Murdered. Shot Dead by a Cold-Blooded Assassin, p. 2. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 17, Number 31. March 28, 1882. (PDF accessed June 16, 2016 at http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH18820328.2.13).

LAH. 1882b. Thought to be the Murderers of Peel, & untitled article, p. 2. Los Angeles Herald, Volume 17, Number 34. March 31, 1882. (PDF accessed June 17, 2016 at http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH18820331.2.8.1).

Parsons, G. W. 1996. A Tenderfoot in Tombstone. The Private Journal of George Whitewell Parsons: The Turbulent Years, 1880-82. Edited, Annotated, and with Introduction and Index by Lynn R. Bailey. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xvi + 253 p.

Tritle, F. A. 1883. Report of the Governor of Arizona Made to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1883, p 12. Washington: Government Printing Office. 14 p. In AZGovs. 1879-1899. (p. 56-71 abs.). AZGovs. 1879-1899. Reports of the Governor of Arizona Made to the Secretary of the Interior. [PDF consists of separately paginated reports by territorial governors to the Secretary of the Interior for 1879, 1881, 1883-1899. Pages that are scans of the back covers of books suggested that reports were separately published and later scanned together. PDF downloaded December 15, 2013 from http://books.google.com/books/download/Report_of_the_Governor_of_Arizona_to_the.pdf?id=ARb1stVcf_4C&hl=en&capid=AFLRE70TJZ16KcyTvirJPbHyR5a74uUUD6Lo48nHR1a_xUwkp2o56006Ox41YUNXurOza2eE7P4NAk8Rjmo5d66DygL4mc4THg&continue=http://books.google.com/books/download/Report_of_the_Governor_of_Arizona_to_the.pdf%3Fid%3DARb1stVcf_4C%26output%3Dpdf%26hl%3Den).

TWE. 1882a. The Coroner’s Inquest. More Evidence as to the Murderers of M. R. Peel. Fifth Day, p 1. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. April 3, 1882. [Page reprinted from Tombstone Daily Epitaph of April 1, 1882.] (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-03/ed-1/seq-1/).

TWE. 1882b. Murder Most Foul. M. R. Peel Shot and Instantly Killed, at the Tombstone Company’s Office in Millville, & The Coroner’s Inquest, & Local Personals, p. 3. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph April 3, 1882. [Page reprinted from March 27, 1882 issue of the Tombstone Daily Epitaph.] (PDF accessed June 13, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-03/ed-1/seq-3/).

TWE. 1882c. The Coroner’s Inquest. Inquiry into the Cause of the Death of M. R. Peel. Second Day & $500 Reward, p 4. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. April 3, 1882. [Page reprinted from Tombstone Daily Epitaph of March 28, 1882.] (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-03/ed-1/seq-4/).

TWE. 1882d. The Coroner’s Inquest. Inquiry into the Cause of the Death of M. R. Peel. Third Day & Desperate Fight. Two Cow-Boy Rustlers Come to Grief, p. 5. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. April 3, 1882. [Page reprinted from Tombstone Daily Epitaph of March 29, 1882.] (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-03/ed-1/seq-5/).

TWE. 1882e. The Coroner’s Inquest. Inquiry into the Cause of the Death of M. R. Peel. Fourth Day, p 6. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. April 3, 1882. [Page reprinted from Tombstone Daily Epitaph of March 31, 1882. (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-03/ed-1/seq-6/).

TWE. 1882f. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph, p. 4. April 17, 1882. [Page reprinted from the Daily Tombstone Epitaph of April 11, 1882.] (PDF accessed June 15, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-04-17/ed-1/seq-4/)

TWE. 1882g. Abducted. Zwing Hunt, the Wounded Cowboy Spirited Away, p. 5. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. May 1, 1882. [Page from the Daily Tombstone Epitaph of Friday, April 28.] (PDF accessed June 17, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-05-01/ed-1/seq-5/).

TWE. 1882h. Death of Zwing Hunt. He is Murdered in the Chiricahuas by Hostile Apaches, p. 1. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. June 10, 1882. (PDF accessed June 17, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-06-10/ed-1/seq-1/).

Wagoner, J. J. 1970. Arizona Territory 1863-1912. A Political History. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. xii +587 p.

Walker, H. P. 1969. Retire Peaceably to Your Homes: Arizona Faces Marshall Law. The Journal of Arizona History, 10: 1-18.

At approximately 8:20 PM the men noticed a fumbling at the door knob of door number 2 and then a heavy rap–probably produced with the butt of a gun. Austin shouted, “Come in.” Someone then flung the door wide open, and a man with a rifle entered and was immediately followed by another who brought his rifle down as he entered. Both assailants fired a single shot almost immediately as they entered. One bullet shot Peel through the heart and because of the close range set his clothing on fire. He rose from his chair and then fell down dead. The bullet that killed Peel came from a rifle that was already in firing position when the door opened. The shot fired by the second man was apparently aimed at Austin. However, the second shot was slightly delayed after the first, possibly because the second assailant was the one who flung open the door. All three of the employees behind the counter were able to drop down behind it, and the shot that missed buried itself in the wall as shown by the lower small circle of Fig. 2. The bullet that killed Peel made a hole in the counter as indicated by the small upper circle.

Both assailants fled after having each fired a single shot. They were masked with handkerchiefs, and the only one who was well seen wore a white hat that he lost on his way to the horses that were held by an accomplice a few hundred yards from the office. Several men reported rockets fired after the assassination.

People were utterly bewildered as to the motive for the attack. The assailants did not demand money or bullion. The night was not stormy, and the apparent use of signal rockets was certainly not part of the normal routine of a robbery. Citizens wondered if the use of rockets indicated that the deed was premeditated and that the rockets were used to inform someone that the deed had been accomplished. Cheyney reported that he felt that the assailants would have had sufficient time from their departure from the office to reach the area from which it appeared that the rockets were launched.

Peel lacked enemies as far as anyone knew. This young man was the son of Judge Bryan Peel, a highly respected resident of Tombstone and was also one of the producers of a well-regarded map of the Tombstone Mining District (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 65; Ingoldsby et al., 1881.). Before moving to Tombstone, Martin Peel had lived in Los Angeles and received training there as an engineer. The Los Angeles Herald stated on March 28 (LAH, 1882a) that “We had the pleasure of knowing deceased intimately during the earlier years of our residence in Los Angeles and always found him a thorough gentleman, honorable and high-minded in all his impulses, a character which he bore amongst all who knew him. His early death casts a deep gloom over a large circle of attached relatives and friends.”

Governor Tritle authorized the Tombstone Epitaph to announce that he was offering a reward of $500 for the arrest of the murderers (TWE, 1882c). The paper duly reported the reward, suggested the County Board of Supervisors supplement it with a similar amount, and stated, “it is more than likely that they will do so at their first meeting in April.” The newspaper was indeed correct, and the County Board of Supervisors during their April meeting TWE, 1882f). authorized Sheriff Behan to offer a reward of $500 for the capture of the murderer of Peel and also another $500 reward for the murderer of “old man McMenomy, who was killed on the San Pedro, near St. David’s, about the same time of the murder of Mr. Peel.”

Events on March 28 may have led to the capture of the assailants (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 302-311; TWE, 1882d). At about 7 PM on the evening of March 28, E. A. Harley, the deputy sheriff in charge of the office in the absence of Sheriff Behan, learned that two men for whom the office had warrants, named Billy Grounds, alias “Billy the Kid,” and Zwing Hunt, would be near Tombstone during that night or early in the next morning. (Zwing Hunt was not related to F. F. Hunt.) The two men had gone to the Chandler milk ranch approximately nine or ten miles east of Tombstone and found that the only person there was a man in charge because the owner was in Tombstone. Two Mexican families lived in a house about 100 yards away from the main ranch house. Hunt and Grounds said that the owner of the ranch owned them $75 and sent a note to the owner in Tombstone by the man in charge. The note asked the owner to send them the money by bearer because they were getting ready to leave the country. The owner instead informed the sheriff’s office of the outlaw’s location. In the meantime, Bull Lewis, a teamster, came to the ranch and was the only person in the house with the outlaws when the posse arrived. A. Harley ordered Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge to organize a posse and to leave town about 1:00 or 2:00 AM so as to be in the proper area to arrest the outlaws. The office arranged for two miners, Jack Young and John A. Gillespie, and a jail guard named E. H. Allen to be members of the posse.

The posse arrived at the ranch just before dawn, tied up their horses a distance from the house, and crept toward it. Breakenridge placed Young and Gillespie at the back door behind a woodpile and told them to be quiet until daylight when he expected that the outlaws would come outside to look for their horses. Allen and Breakenridge went to the front of the house where there was both a window and a door. Just as they arrived there, Gillespie knocked on the rear door and when asked who was there replied, “It is me, the sheriff.”

The two outlaws opened the door and shot Gillespie dead and also shot Young in the thigh. The front door then opened and Bull Lewis ran out shouting, “Don’t shoot, I am innocent.” A shot from the front door creased Allen across the neck, knocking him senseless. Breakenridge heard someone step toward the door from the inside and grabbed Allen by his collar and dragged him down the bank of a dry creek in front of the house. Breakenridge jumped behind a small tree just as someone shot from the front door, and the bullet hit the tree. The person who fired the shot stepped to the door to fire another, and Breakenridge fired one barrel of his shotgun, loaded with buckshot, into the opening. The buckshot hit Grounds in the face, and he fell to the ground. Meanwhile Allen had regained consciousness. Hunt came around from the back of the house calling out, “Billy, Billy.”

Both Breakenridge and Allen fired at Hunt, and he disappeared, and they thought that he had been shot. Young called out that he had been shot, and Breakenridge ran to him and helped him get to another house about 100 yards from the main ranch house. Allen laid behind the creek bank and guarded the front door so that no one could come out and shoot Breakenridge. All of the shots up to that point had been within a period of two minutes.

Breakenridge took Young to a place where he could have attention once a doctor arrived and returned to Allen, told him to guard the house, said that he thought Hunt was wounded, and that he would go up the creek to look for him. By then it was daylight, and the two men could see the feet of Billy Grounds sticking just out of the door.

Breakenridge walked about 100 yards up the creek when he heard the bear grass rustle and aimed his gun at the area and shouted, “Throw up your hands.” Zwing Hunt immediately raised his hands, and Breakenridge ordered him to lie down and put his hands in front of him. After Hunt did that, Breakenridge sent Allen to get a milk wagon that was at the other house and to get the men there to help take Hunt to that house. The outlaw was shot through the left lung, and every time he breathed, air whistled out the wound in his back where the bullet exited. Breakenridge took off his coat and made a pillow with it for Hunt, and when Allen and the other men arrived with the milk wagon took Hunt to the house. He sent Bull Lewis to Tombstone with a message asking for an ambulance and the doctor. The posse found Gillespie dead at the back door, and Grounds still alive, although he never recovered consciousness. The posse put the outlaws on a mattress, made a fire, put hot water bottles at their feet, and did what they could to make them comfortable.

The doctor eventually arrived with a crowd that included several friends of Breakenridge because people had gotten the belief that he had been killed. The men returned to Tombstone with Gillespie dead in one wagon, the badly wounded Grounds and Hunt in another, Allen and Young in the ambulance, and Breakenridge–the only posse member not shot–riding on a horse. Young told Breakenridge that Gillespie had wanted to run for sheriff in the next election and decided to make the arrest alone and thereby get credit for it. Hunt said that he thought a posse led by Earp was after them and would not have fought had he known otherwise.

People began to suspect that Grounds and Zwing Hunt were the assassins or accessories to the murder (Parsons, 1996, p. 215). The warrants upon which the posse acted were only for charges of rustling, and it seemed improbable that the rustlers would’ve resisted to the point of death (LAH, 1882b). Moreover, one of the rustlers wore a hat that was much too large for him, and one of the assassins had lost a hat near the scene of the assassination. Shortly after the shooting, Hunt told Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge that he had come to the place with the intention of “downing” Jack Chandler who he said owed him money (AWC, 1882b). Hunt then asked what the charges were against him and seemed very relieved when the deputy sheriff replied “Grand larceny.” His evident relief resulted in the suspicion that he and Grounds were involved in the assassination. At some point the horses of the two outlaws were put into Dunbar’s corral in Tombstone, and the boots of the men were confiscated as potential evidence. The possible involvement of the two outlaws was examined during the lengthy Coroner’s inquest that started on March 27.

The first witness during the inquest was George W. Cheyney, a clerk, who described the details of the assassination as given above and drew the diagram of Fig. 2 (TWE, 1882b). Cheyney added that after the killing he and Austin and Hunt armed themselves, went out onto the porch and then walked along the road several hundred yards where they met the watchman who was coming down the hill. They sent him to rouse additional men, and within five or six minutes several men had collected and divided into parties that went around the house to the office door. Cheyney found that Peel was lying on his back with his head and shoulders on the porch and had no pulse. He found that the victim’s clothing was on fire and together with other men carried him into a chamber adjoining the office. Cheyney was not looking at Peel at the time the assassins came in and could not say whether or not weapons were pointed at him in particular but reported that the rifles were leveled when the men came in. He knew of no enemies of Peel, had no idea why the deed was done, and speculated that the object might have been robbery. He saw two rockets shortly after the shooting on a line between Charleston and Tombstone and noted that some of the other men reported seeing the rockets themselves.

F. F. Hunt, an assayer, next testified that he agreed with Cheyney’s testimony, knew of no personal feeling or cause for the attack, felt robbery was the only reason he could think of, stated that he did not know how much bullion was in the vault in the office, and reported that he did not know of any money in the vault.

Miss Mary Melane then stated that she was the housekeeper in the building and heard everything distinctly in her room that was right over the office. Contrary to what other witnesses said, she reported hearing Peel cry “Oh!” and recognized his voice. She knew of nothing of a personal nature that would have led to the incident.

WM. H. Dugan, a laborer, testified that at about 8 PM he was working wheeling in “tailings,” about 150 yards from the company office and heard what sounded like two shots. He saw two or three objects rapidly pass by the farther end of the office and go towards an adjacent woodpile. He saw several flashes before the shots and afterwards saw a rocket in an approximately eastern direction. He never heard anyone speaking of the victim with anything but respect.

George Fraser, an engineer in the Gird mill, was in his house at Charleston at about 8 PM when the watchman came to the door and told him to arm himself and go to the office as fast as possible because there had been an attack. He did not see or hear the shooting but did report observing several flashes and found the bullet that had killed Peel in a pigeonhole about three inches from the top of the counter.

Henry Nelson, a melter for the company, did not see any suspicious circumstances before the shooting but saw flashes afterwards in an easterly direction and then saw one in a northerly direction. He picked up a hat that was lying in front of the office door and stated that he believed that the hat that was shown to him in court was the same one that he had found. Nelson reported that there was no evidence of a thunderstorm and nothing to indicate lightning.

On the second day of the inquest (TWE, 1882c), E. T. Hardy, a Bisbee merchant, stated that he did not remember selling either the hat or handkerchief that were shown to him in court. For reasons that are not given in the newspaper article about the inquest, Hardy testified that he knew a man named Henry and last saw him it Bisbee approximately four or five days previously. Hardy met him on the road about 10 days previously and noted that he was armed with a gun and six-shooter and said he was shooting rabbits. Probably there was speculation that Henry was involved in the murder.

Henry Raymond testified next and said that he lived in Tombstone but had been living in Bisbee until the night before the murder. He left Lewis Spring about 10 AM on the day of the murder (Saturday), passed through Charleston, went about a quarter of a mile from the Boston Mill and stayed there until 4 PM. He then continued on to Tombstone, stopping about an hour to hunt rabbits. He saw no one on the road except some men blasting rock below Charleston on the river and three men sitting beside the road. Raymond reported that he never wore a white hat, never saw Judge Peel before outside of Tombstone, did not recognize Austin, saw no lightning, bought his hat and boots from Glover approximately a week before Christmas, and did not buy any handkerchiefs from the merchant when he bought the hat and boots. Raymond then contradicted himself by stating that it was 12 o’clock on Friday when he met the men below Charleston and that he had arrived in town Friday night and was in Tombstone all of the day of the murder.

W. L. Austin, mill manager, corroborated Cheney’s testimony and testified that he had a revolver near him and grabbed for it. He thought that Peel made the same move and that that was the cause of the shot. Austin dropped and thus escaped the shot that was fired at him. He subsequently examined the tracks made by the assailants and concluded that one of them had boots that were about medium-size while the other had somewhat peculiar boots. The boot prints of one assailant were 9 ½ inches long and 3 ½ inches wide and had tread on the side. The other assassin made larger tracks, with a hollow in each heel. One of the horses was large and had been recently shod and must have been a draft animal because of the type of its shoe. The tracks of the assailants headed in the same direction as where he saw the flashes.

There were only two witnesses on the third day of the inquest (TWE, 1882d). J. A. Nolly, a carpenter and miner residing in Charleston, stated that about two minutes after the noon whistle blew on the day of the murder he saw Henry Raymond. Henry had a gun and pistol and wore a light drab hat that was lighter in color than the hat that Nolly found near the mill office. Isaac Jacobs stated that Henry Raymond began working for him on March 26 and that he bought some rabbits from him the day before. He last saw Raymond at about dusk the night of the murder.

The fourth day of the inquest included testimony from three witnesses (TWE, 1882e). T. J. Harrison, a resident of Charleston, stated that the hat shown in court looked like one that he used to wear. He was not positive if it was the one, but thought it was. He obtained the hat from Fin Clanton approximately last December, and Clanton had said that he obtained it from Mr. Ayres, a saloon keeper in Charleston.

Edward Overton said that he lived about six miles below Charleston, at Lewis Springs. At noon on Sunday, the day after the killing, two young men came by on horseback and asked for food, stating that they had not eaten since the previous morning. He fed them, and they laid down to rest. Company C of soldiers later came by. Overton told the young men that there were soldiers in the area, and they became “very much excited,” talked together in low tones in the corner of the house away from him, and afterwards stated that they did not want to be seen by anyone. Overton told the men that the soldiers were not looking for them but rather for Indians. The men remained with him until about five minutes before sunrise on Monday morning, were afraid while there, and told Overton that they were escaping from justice. Overton subsequently visited the hospital and reported that the men there who had been shot were the ones who stayed with him. One of the men recognized him and said he wished they had stayed at his house. One of the men asked two or three times if Overton had heard about anyone being killed at Charleston lately and seemed very relieved when Overton said no because he did not learn about the murder of Peel until later. Overton saw the horses at Dunbar’s corral that were said to have been taken from the men and recognized them as the ones they had ridden away from his house.

Austin testified that he had examined the boots of Grounds and Zwing Hunt and that the tracks he saw at the mill might have been made by them. However, he stated that he could not swear to that although he was “quite positive in my own mind that they are the ones.” He stated that he had examined the horses at the corral taken from Grounds and Hunt and that one of the hoofs corresponded very nearly to one of the tracks that had been made at the mill, but that he did not recognize the other horse. He suggested that three other persons, Henry Fishback, McClure, and a carpenter could better identify the horses and boots then he could. Austin had examined the guns that the sheriff had in his charge but could not identify them.

The inquest concluded on April 3, the fifth day of the inquest (TWE, 1882a). Henry Fishback, a resident of Charleston and an amalgamator for the Tombstone M. & M. Co., testified that he had examined the tracks of the assassins the morning after the shooting and thought that he could recognize the boots that made them. One was made by a heavy boot, and the other looked as though it had been made by a "fine one.” The coroner produced the boots from Grounds and Hunt, and the witness stated that one of the pair might be those that made the tracks but that he was not sure. He had examined the horses at the corral and thought that the larger of them might’ve made one of the sets of tracks that were at the mill but did not think that the other horse could’ve made the other set of tracks.

Ernst McClure, a Charleston merchant, examined the boots and stated that a pair of them might have produced the tracks at the mill. He also thought that one of the horses at the stable could’ve made the tracks at the murder site.

J. E. Smith, a carpenter in Charleston, examined the tracks at the mill and concluded that none of the boots made them. He thought that one of the horses in Dunbar’s corral might have made one of the set of tracks but remarked that he was not an expert trailer of either man or stock.

D. H. Holt examined the hat that Cheney had given him the night after the shooting. Another man in Charleston had one just like it and said that he got it at McKean & Knights.

Dr. H. M. Matthews testified about the wound that killed Peel. It was made by a ball that passed through his right side and through the heart, killing him instantly.

The inquest then recessed from 12:30 until 1 PM. The jury convened again at 1:30 PM and after deliberation concluded that the victim’s name was M. R. Peel, aged about 26, a native of Texas, and that he died on the night of March 25 at the office of Tombstone M. & M. Co. mills from a gunshot wound “inflicted by parties unknown to the jury.” The evidence possibly implicating Hunt and Grounds and the often uncertain or conflicting conclusions of witnesses simply did not provide strong enough proof to conclude that the rustlers had been responsible for the assassination.

Any hope of obtaining information from Zwing Hunt or of prosecuting him at least on the rustling charges literally vanished on the night of April 27 between 8 and 9 PM (TWE, 1882g). Authorities had deposited him in the county hospital to recuperate. On Monday, April 24 supervisor Tasker had spoken with Supervisor Joyce about removing the outlaw to the jail. However, the latter supervisor felt that Hunt was still in such a serious condition that a transfer would endanger his life, and that there was no current danger of the man escaping. The doctor treating him, Dr. Goodfellow, said that the man’s condition was so critical that he would have opposed such a move as cruel and liable to kill Hunt. He also opposed moving the patient to a place that would be more comfortable than the jail because even that transfer would endanger his life.

Meanwhile Hugh Hunt the brother of Zwing had arrived in Tombstone on Sunday April 23. The brother and the father of both men were respectable merchants in Texas and reportedly “well off.” After his brother arrived, Zwing Hunt was in very good spirits and seemed to be quickly improving in health. In the last week of April, the Tombstone Epitaph had contained a communication warning of the possibility of an attempt being made to rescue the prisoner from the hospital, but a guard was not posted to prevent his escape.

Someone apparently took Zwing Hunt out of the hospital between 8 and 9 PM on April 27 and drove him away in some sort of a conveyance, the patient still apparently being too weak to have left on his own. When Hunt disappeared, there was no one in the front room with him, but there were two patients in an adjoining backroom and three or four convalescent patients sitting beneath an awning in the rear of the building. All of them said that they heard nothing and did not know about the disappearance until a few minutes before 9 PM when the janitor went into the front room and found that Hunt was gone. A messenger was immediately sent to tell Dr. Goodfellow, who immediately informed the sheriff.

Hugh Hunt returned briefly to Tombstone on June 9, 1882 and reported the details of his brother’s death (TWE, 1882h). He also claimed the horse and guns that belonged to Zwing at the time of his arrest (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 312-313). After he and his brother escaped from the hospital, they rode to the Dragoon Mountains on horseback and reached there at night. Zwing was sick and very weak and vomited several times during the journey and refused to go any further after they reached the Dragoons. Their original plan had been to continue on until they reached the Chiricahua Mountains that would provide better opportunities for hiding from the law. They rested the next day in the Dragoons and then at night rode towards the Chiricahuas. Zwing recovered rapidly, and the brothers spent all of May wandering through the Chiricahuas. On May 30 they camped in Pinery Canyon. The next morning Zwing baked bread, and Hugh made coffee and broiled some meat. The men had just started to eat breakfast when a volley of gunshot was fired toward them. Hugh at first thought that the shots were from the sheriff’s posse, but when he looked quickly around saw several Indians nearby taking aim with their rifles. Zwing pulled out his gun and cried “damn it! go to shooting.” It was the last he ever spoke because the Indians shot him four times, once in the left hip, once in the abdomen, and twice in the head. After his brother died, Hugh ran into the heavy timber and headed for their horses that were hobbled nearby. The Indians, who were on foot, ran after him and kept up a continuous firing. He jumped on a horse bareback without removing the hobbles and rode for about half a mile until he felt it was safe to remove the hobbles. Hugh reported that his brother had several times told him that he thought the posse at the Chandler ranch was the Earps and that was why he fought. A sheriff’s posse subsequently dug up the body and identified it and found that the wound in Hunt’s lung was still not healed (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 312).

On June 9, 1882 a Cochise County grand jury that had been impaneled to in part investigate the operation of the county reported that at the request of the Court it had made a “very searching” inquiry into the escape of Zwing Hunt from the County Hospital (AWC, 1882e). The jury concluded that, “his escape was owing to negligence of the Sheriff. We are of the opinion that this officer entirely and inexcusably neglected to take any measures to prevent his escape or abduction.”

The bold killing of a well-respected young man in the office of Richard Gird caused considerable consternation among residents of Tombstone. George Parsons, a well-respected resident, wrote about the incident in his diary on March 26 (Parsons, 1996, p. 214-215). “Another murder and this time of the most startling nature. Poor Peel was shot and instantly killed by two masked men at the T. M. & M. Co’s office, Charleston, last evening between eight and nine o’clock. No reason whatever assigned for the cause. Possibly an attempt at theft and perhaps simply thirst for gore on account of attitude of the company against the outlaw element. Now that it has come to killing of upright, respectable, thoroughly law abiding citizens–all are aroused and the question is now, who is next.”

The assassination of Peel, the gunfight at Chandler’s ranch that resulted in the death of a member of the posse, and the escape of Zwing were but some of the many lawless incidents in and around the San Pedro River Valley and other regions of Cochise County. The fact that Hugh Hunt felt safe returning to Tombstone after helping a prisoner escape, suggested that law enforcement was somewhat sporadic. Governor Tritle arrived in Tombstone on March 27 to investigate the violence (AWC, 1882c; Parsons, 1996, p. 214-215, 218; Wagoner, 1970, p. 194-200). He was greatly concerned by what he found and concluded that the civil authorities were powerless or unwilling to afford proper protection to life and property. He facilitated the formation of a posse to assist Deputy United States Marshall J. H. Jackson in protecting life and property and declared that when the number of the posse reached 30 he would muster them into service as a militia company. Tombstone citizens also met and discussed steps for organizing an additional military company and appointed a committee of citizens to seek donations to defray the expenses and pay the men who would assist the marshal.

The Los Angeles Herald pressured Governor Tritle to take strong action (LAH, 1882b).

There is a good deal of curiosity to know what Governor Tritle has been about all this time. In face of a crisis which has practically assumed the dimensions of an insurrection he does not seem to have thought it necessary to interpose the weight of his official authority. . . The murder of young Peel, itself following on two border tragedies, and followed in turn by two more–altogether scarcely needing 10 days for their accomplishment–will not only check the growth of Arizona and population but will actually depopulate the territory unless a remedy–a quick and sure remedy–is found for the disorders.

Tritle did take decisive action. While still in Tombstone, he telegraphed President Chester A. Arthur on March 31, described the turbulent conditions caused by the cowboys and requested a congressional appropriation of $150,000. General Sherman came to Tombstone on April 7 and was also dismayed by the violence and lawlessness.

Pressure continue to build for more action. The Arizona Weekly Citizen on April 9, 1882 (AWC, 1882c) wrote about a feeling of insecurity by citizens.

There is a general feeling of insecurity, owing to the evident powerlessness or unwillingness of the civil authorities to afford protection to life and property. The condition of affairs is insurrectionary and processes of law cannot be served without violence. A virtual reign of terror exists, which makes peaceable, law-abiding citizens unwilling to serve as posse and stifles the free expression of opinion upon the tragic occurrences of the past few weeks.

President Arthur heeded the advice of Governor Tritle and General Sherman and on April 26, 1882 sent a message to Congress stating that the governor of Arizona had reported that “violence and anarchy prevail, particularly in Cochise County and along the Mexican border.” The president stated, “Much of this disorder is caused by armed bands of desperados known as ‘Cowboys,’ by whom the depredations are not only committed within the Territory, but it is alleged predatory incursions are made therefrom into Mexico.” He requested that Congress modify an 1878 law to allow military forces to be used as a posse comitatus to help civil authorities (Arthur, 1882a). Congress responded by informing the president that he already had sufficient authority. The president responded with a proclamation on May 3, 1882 that bluntly threatened to use military forces if the lawbreakers in Arizona did not disperse (Arthur, 1882b; AWC, 1882d).

Whereas it is provided in the laws of the United States that--

Whenever, by reason of unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages of persons or rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States, it shall become impracticable, in the judgment of the President, to enforce by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings the laws of the United States within any State or Territory, it shall be lawful for the President to call forth the militia of any or all the States and to employ such parts of the land and naval forces of the United States as he may deem necessary to enforce the faithful execution of the laws of the United States or to suppress such rebellion, in whatever State or Territory thereof the laws of the United States may be forcibly opposed or the execution thereof forcibly obstructed.

And whereas it has been made to appear satisfactorily to me, by information received from the governor of the Territory of Arizona and from the General of the Army of the United States and other reliable sources, that in consequence of unlawful combinations of evil-disposed persons who are banded together to oppose and obstruct the execution of the laws it has become impracticable to enforce by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings the laws of the United States within that Territory, and that the laws of the United States have been therein forcibly opposed and the execution thereof forcibly resisted; and

Whereas the laws of the United States require that whenever it may be necessary, in the judgment of the President, to use the military forces for the purpose of enforcing the faithful execution of the laws of the United States, he shall forthwith, by proclamation, command such insurgents to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes within a limited time:

Now, therefore, I, Chester A. Arthur, President of the United States, do hereby admonish all good citizens of the United States, and especially of the Territory of Arizona, against aiding, countenancing, abetting, or taking part in any such unlawful proceedings; and I do hereby warn all persons engaged in or connected with said obstruction of the laws to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes on or before noon of the 15th day of May.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed. Done at the city of Washington, this 3d day of May, A. D. 1882, and of the Independence of the United States the one hundred and sixth. CHESTER A. ARTHUR.

Violence declined substantially after the proclamation (Tritle, 1883, p. 12). It is not clear how much that was due to the proclamation, how much was due to rustlers having been killed, how much due to ranchers and other citizens having organized for protection, and how much due to cowboys departing for more promising regions (Walker, 1969). Deputy Sheriff Breakenridge declared (Breakenridge, 1992, p. 299), “A lot of the rustlers had been killed off by the Mexicans in rustling stock and in quarrels among themselves when they were drinking. The stockmen had organized for self-protection, and the rustlers got out of the country as fast as possible.”

Literature Cited

Arthur, C. A. 1882a. To the Senate and House of Representatives. Executive Mansion, April 26, 1882, p 4688-4689. [Letter to Congress about violence in Cochise County.] In Richardson, J. D. 1897. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Prepared Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing, of the House and Senate, Pursuant to an Act of the Fifty-Second Congress of the United States. (With Additions and Encyclopedic Index by Private Enterprise). Volume X. Bureau of National Literature, Inc., New York. p. 4503-4975. (PDF accessed June 18, 2016 at https://archive.org/details/compilationofmesv10unit).