Railroads Part 1.

The Arrival of the Railroads.

© Gerald R Noonan 2016

The federal government and railroad executives initially viewed Arizona as a sparsely populated area that needed to be crossed by railroads to connect the East with Southern California and the Pacific Ocean (Myrick, 1981, p. 13-68, 163-176). The territory in the early 1870s was sparsely populated with most of the urban population located at Tucson, Prescott, La Paz, Yuma, and scattered mining camps. An 1870 census that did not count Native Americans reported only 9658 people in the territory. Those settlers that did live in Arizona looked forward to the railroads as a means for transporting gold, silver, copper and other ores, shipping freight, livestock and produce, and providing more comfortable, rapid and economical transportation of passengers. Senior officers of the U.S. Army realized that a railroad across Arizona would be useful in transporting troops and military cargoes and in fighting the Apaches.

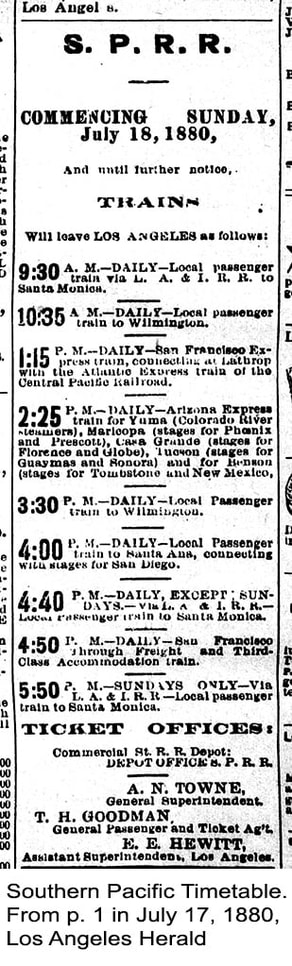

The Southern Pacific railroad was the first to reach the San Pedro River Valley, and its arrival at the valley depended upon the railroad fooling and outmaneuvering the army in Yuma. The “Big Four” executives of the Central Pacific wanted to build across Arizona from California to stave off competition from other railroads as long as possible (Best, 1941, p. 5-6; Myrick, 1981, p. 13-58). C. P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins had become experienced at building railroads through the long years of constructing the Central Pacific, the western part of the first transcontinental railroad that joined the Union Pacific in Utah on May 18, 1869. The Big Four noted with interest that a congressional bill of July 27, 1866 that authorized the construction of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad from St. Louis to San Francisco contained a provision granting permission for the Southern Pacific Railroad of California to meet the Atlantic & Pacific near where Needles occurs today. The executives therefore acquired the Southern Pacific in 1868 and maneuvered to gain additional authority for building eastward. An 1871 congressional bill authorized the Texas & Pacific Railroad to build across Texas to El Paso and then continue onward through New Mexico and Arizona to San Diego and provided land grants as an incentive. The bill also authorized the Southern Pacific to connect at Yuma with the Texas & Pacific. The Southern Pacific thus had permission to lay track toward northern and southern Arizona. However, it still needed permission to lay track across Arizona.

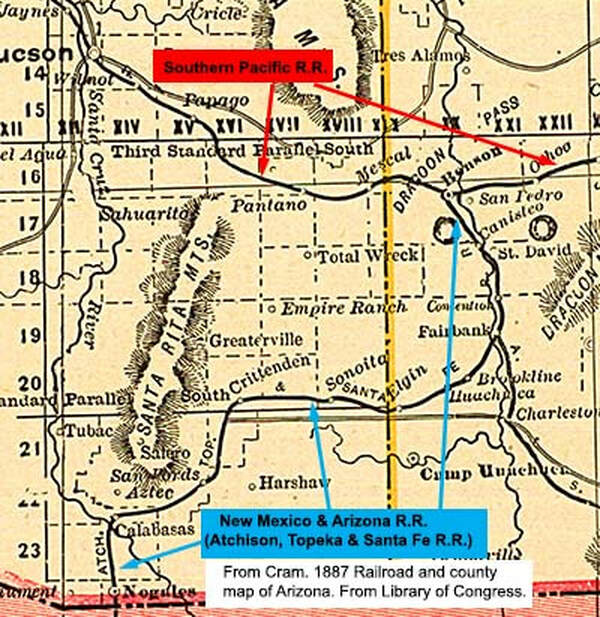

Since Congress seemed unlikely to grant such permission because of the busy activities of Texas & Pacific lobbyists, the Southern Pacific requested approval from the Arizona Territorial Legislature, and Estevan Ochoa of Tucson introduced the necessary bill. People in northern Arizona opposed the bill because they wanted the railroad to come through the north. A compromise was finally reached in a Territorial Act of February 7, 1877 whereby the railroad would enter southern Arizona at Fort Yuma and generally follow the 32nd parallel and would also proceed into northern Arizona at the area of current day Needles and mostly follow the 35th parallel.

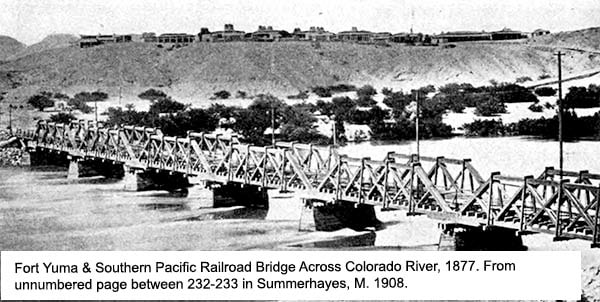

The Southern Pacific built toward Yuma and by the latter part of August, 1877 had put in place four of the seven piers required for a 667 feet-long wooden bridge that would span the Colorado River at Yuma. Political intrigue then moved into overdrive. Two officials of the Texas & Pacific had been watching the situation at Yuma and went to San Francisco to complain to Major General Irvin McDowell. Their complaints produced a blizzard of telegrams and other communications between railroad officials, military officers, and politicians (McCrary, 1878).

On October 18, 1876, military authorities in California had given the Texas & Pacific Railroad permission to break ground on the Fort Yuma military reservation for the purpose of crossing the Colorado River. General McDowell, Commander of the Military Division of the Pacific, on November 27, 1876 revoked that permission until the War Department could rule upon the matter. Meanwhile on April 11, 1877 the Secretary of War gave permission to the Southern Pacific to build a railroad provisionally through a corner of the Fort Yuma reservation. The Secretary of War stipulated that permission was subject to the condition that the railroad apply to Congress for a grant of right-of-way over the reservation, and if the right-of-way was not granted by Congress at its next session, the railroad must remove the track from the reservation and abandon the road. On August 22, 1877, the military granted a similar permission to the Texas & Pacific Railroad. The latter company protested that grants to lay track across the reservation were injurious to its interests because the military had in November 1876 revoked a similar permission that had been granted the company in October of that year, a fact that was overlooked by the military when it granted permission for track laying in 1877. On September 1, 1877, the Secretary of War suspended all authority for either railroad to build across the reservation until both companies could be fully heard or until Congress decided the matter.

The stop waste ploy at Yuma

Officials of the Southern Pacific pointed out that heat at Yuma could damage expensive lumber that had been transported there for use in the bridge. On September 6, the suspension of track laying was modified to allow the Southern Pacific to continue work within the military reservation “only to the extent of staying waste or injury to the property, and opening the way to the passage of steamboats.” The modification was intended to prevent damage to wood from the heat by incorporating it into the bridge and to allow the opening of a 93 ½ foot swing span of the bridge on the Arizona side so that steamers could follow the deepest channel of the Colorado River.

On September 29, 1877, the Arizona Sentinel reported (AS, 1877a) that the Southern Pacific railroad bridge was virtually finished that day except for the laying down upon it of the rails. The paper reported that the rail laying could be done within a few hours and correctly predicted that: “The coming week will show what attention the R. R. Company is disposed to pay to the late orders of the Secretary of War. . . .”

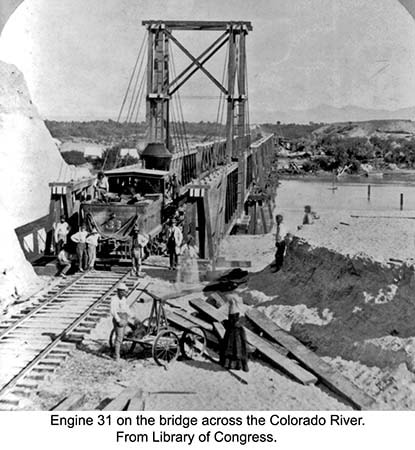

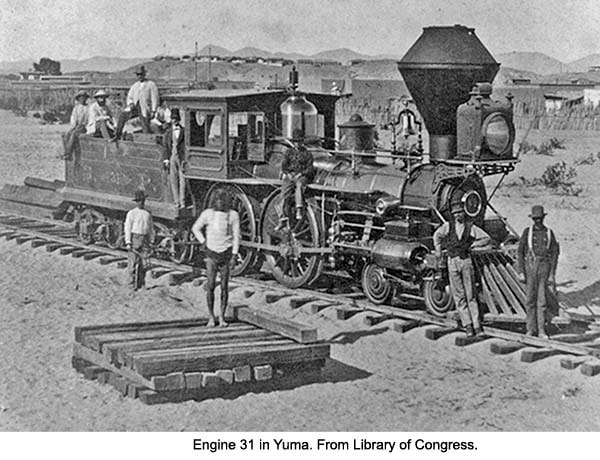

The officials of the Southern Pacific were determined to cross the Colorado River. On the night of Saturday, September 29, 1877 Major Dunn, the Commandant of Fort Yuma, suspected that something might happen that night and posted a sentry at the bridge (Altshuler, 1980; AS, 1877b). However, nothing seemed to happen as the night proceeded, and the Major had the sentry removed at 11 p.m. At approximately midnight, laborers of the Southern Pacific began stealthily laying track across the bridge. At approximately 2 a.m. workmen accidentally dropped a rail on the bridge and awakened Major Dunn. The latter had little in the way of troops with which to stop the work because the garrison then consisted of only the major, a medical officer, a sergeant, two privates, and a prisoner who was serving a court-martial sentence. Major Dunn, a sergeant, and a private marched to the bridge and halted work with fixed bayonets. The superintendent of the railroad workers let the army have its way for the moment. Suddenly without notice the guard posted on the bridge found that a carload of rails was moving toward him and that he had little choice except to step aside. The major ordered the railroad superintendent to consider himself under arrest but had inadequate force to back up his order and wisely retired to his quarters in the Fort. He sent a telegram to his superiors: “I gave orders yesterday to the superintendent to stop all work of construction within the limits of the reservation. After 12 o’clock last night they commenced laying track to and across the bridge. I tried to stop the work, but not having any force, could not. They propose to run a train across this morning.” The Southern Pacific indeed did run a train, and by sunrise engine No. 31 became the first locomotive on the first track laid in Arizona.

When the Army sent additional troops to stop the further laying of tracks, people in Yuma and elsewhere vigorously protested and lobbied for permission for the railroad to continue construction across Arizona. C. P. Huntington of the Southern Pacific attempted to mollify the military in an October 5, 1877 communication to the Secretary of War. Huntington stressed that “Whatever may have happened at Fort Yuma, I am satisfied that at most it can only be a misunderstanding of instructions of the officers on one side or the other, or perhaps on both.” Huntington pointed out that the completion of the bridge was no interference with the rights of the Texas and Pacific because that company was free to build their own bridge. He tellingly wrote that: “The difference between the companies being that we have one continuous completed road ready to occupy the bridge, while the complaining company has none nearer than eastern Texas, 1,250 miles away.” Huntington noted that the Texas & Pacific was unable to lay tracks unless financially assisted by the United States. Protests about the military blocking Southern Pacific construction included complaints from, the city of Yuma, Kerns & Mitchell Overland Mail Contractors, messages from merchants, a complaint from the Postmaster-General about military interference with mail delivery, and communications from irate private citizens.

Senior military officials knew that the completion of a railroad across Arizona would greatly help them in their attempts to pacify the Apaches, and they realized the benefits that the railroad would bring to civilians. On October 7, 1877, General Sherman wrote to the Secretary of War stating that the Southern Pacific “has been a little presuming in the matter of finishing their bridge across the Colorado River, but the government and the people of the United States have so much reason to be thankful to anybody for building a railway from San Francisco to Fort Yuma and across the Colorado, that I hope some allowance will be made.” The general recommended that the Secretary agree to the location of the road across the reservation with the use of 100 feet on each side of the track and leave the company to petition Congress for title to the land. The Secretary of War did not agree and felt that Congress alone had jurisdiction in the matter. However, on October 9, 1877 President Hayes directed that the military not interfere with the “temporary use by the Southern Pacific Railroad Company of that portion of the railroad and bridge within the Fort Yuma reservation.” and stipulated that the permission he was granting was subject to the approval of Congress at its next regular session. Congress did not grant permission for the bridge and tracks until August 15, 1894.

Onward to New Mexico

The Southern Pacific suspended track laying in the Yuma area (Myrick, 1981, p. 30-57). Senior railroad officials wanted to pay down debt before undertaking more construction. Moreover, the officials knew that a,cts of the territorial legislature were subject to revocation by Congress within two years of their passage. Citizens in both California and Arizona filed petitions with Congress supporting the construction of the Southern Pacific railroad across Arizona, and a measure to repeal the Territorial Act authorizing Southern Pacific construction died in the House. The railroad officials decided to continue track laying across southern Arizona under the auspices of a separate Southern Pacific Railroad Company that was incorporated under Arizona laws on August 20, 1878. Construction resumed, and on the afternoon of March 17, 1880 the railroad reached Tucson, and regular train service began on March 20 after a welcoming ceremony. On September 22, 1880, the Southern Pacific Railroad Co. (of Arizona) reached the border with New Mexico. Track laying continued eastward under the name of Southern Pacific Railroad Co. (of New Mexico) until the tracks joined those of the Santa Fe in Deming on March 7, 1881. Southern Arizona finally had a railroad connection to both the East and West.

Railroad impacts on the San Pedro River Valley

The railroad reached the area of current day Benson in the early summer of 1880 (Myrick, 1981, p. 57-61). As we shall see below and in a forthcoming second article about railroads, the arrival of the Southern Pacific at Benson had considerable impacts within the San Pedro River Valley. The Big Four realized that the Middle Crossing of the San Pedro River was a natural place for the establishment of a new town. They had the Pacific Improvement Co., a holding company created by them to manage their investments outside of their direct railroad holdings and private estates (Coman, 1942), plat a town there named after William B. Benson, a friend of Charles Crocker. The town was located on high ground to avoid floods and the malaria prevalent along the river. Sales of lots in the new town began on June 21, 1880, and regular railroad service to and from Benson started the next day. Benson rapidly grew in population and within six months had four stores, several shops, a hotel and several saloons. The town rapidly became a transportation hub. Stagecoaches and freight wagons trundled between it and mining areas and population centers such as Tombstone. By 1884 the town was nearly recovered from the effects of a recent fire (Elliott, 1884, p. 242). Just east of it the Benson Smelting and Mining Company of San Francisco operated a smelter on the north side of the railroad. From March 1883 to January 1884 the smelter produced $725,000 in bullion. Approximately half of the ore for the smelter came from Arizona, a quarter from Sonora, and another quarter from New Mexico. The population of the town reached approximately 500 inhabitants in 1885 (TT, 1885).

The presence of the Southern Pacific and railroads that would be built within the valley facilitated the movement of cattle into and out of the San Pedro River Valley and helped promote the over stocking of the valley with livestock and the subsequent severe overgrazing of its grasslands (Sayre, 1999).

Before the founding of Benson and Tombstone, Tres Alamos had been the largest population center In the San Pedro River Valley. The advent of the Southern Pacific Railroad and the development of profitable mines in the Tombstone and Bisbee areas made Tres Alamos a less profitable venue for general merchandise stores and stagecoach companies and led to the start of a decline in importance of the latter settlement. The Hooker family had maintained in Tres Alamos the very well-regarded Tres Alamos House that supplied lodging and provided excellent food. Hooker realized that the need for travel lodging at Tres Alamos would soon decline and in early February 1879 announced that the facility was for sale or rent (AC, 1879a). Kinnear in early March 1879 dropped Tres Alamos from his stage route between Tucson and Tombstone (AC, 1879b).

The August 28, 1880 issue of The Arizona Citizen contained further news foreshadowing a decline in the importance of Tres Alamos relative to other settlements in the valley (AC, 1880a, 1880b). Mister Wilt had moved his stock of merchandise from Tres Alamos to Benson. The bridge at Tres Alamos and the road on both the east and west sides of it were in very bad shape. In September 1886, the federal government ordered the post office at Tres Alamos closed, with mail for that place to be sent to Benson (CC, 1886).

Railroads promoted the settlement of the San Pedro River Valley by advertising for and transporting new settlers into Arizona. See for example the 1880 advertising circular (ATS, 1880) of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

The New Mexico and Arizona Railroad

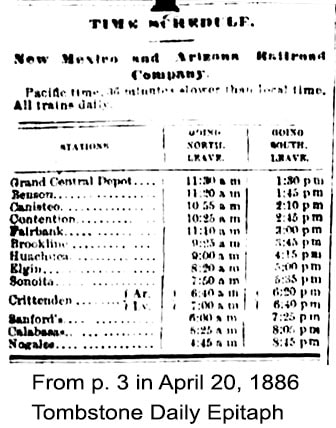

The Upper San Pedro River Valley gained additional railroad service when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, operating under the name of New Mexico and Arizona Railroad, decided to construct an 88-mile line in 1881-1882 (Myrick, 1981, p. 263-296; AS, 1881). The new tracks would connect with those of an affiliated Mexican road to Guaymas and would provide the first AT&SF outlet on the Pacific Coast. The New Mexico and Arizona Railroad Company was incorporated under Arizona laws on June 17, 1881. The company successfully negotiated with the Southern Pacific for the right to run trains over the tracks of the latter between Deming, New Mexico and Benson. It then laid tracks southward from Benson to the area of Contention and the junction of the Babocomari and San Pedro rivers. The track then extended westward along the Babocomari River and crossed a summit to the watershed of Sonoita Creek, extended westward and then southwestward and finally went to Nogales where it met with the affiliated Sonoran line.

Working on the new railroad could be dangerous. In February 1882, a worker who was laboring near the mouth of the Babocomari River made the mistake of attempting to tamp down an explosive charge with an iron bar (TE, 1882). The resulting explosion resulted in him losing both eyes and one hand.

By January 11, 1882 the railroad had nearly completed a two-story depot at the Contention stop. Some residents of the old city of Contention were already preparing to move to near the depot. On January 15, 1882, the railroad transported its first group of passengers from Contention City to Benson (TWE, 1882a). The railroad returned the passengers by special coach to Contention City where they were treated with “an elegant dinner” and then taken by carriages to Tombstone. Trains ran between Benson and Contention with a charge of $1.50 per passenger for the 15-mile trip and a fee of $0.11 per hundred pounds of merchandise.

The railroad installed the “Calabasas Wye” or “Calabasas Y” just north of the junction of the Babocomari and San Pedro rivers to turn locomotives (AWC, 1882a). The name of the Wye apparently came from the town of Calabasas which the railroad reached on the Santa Cruz River just north of Nogales. For a while the place was called Kendall in honor of the civil engineer J. G. Kendall who supervised the construction of the next nine-mile section of track. After 1882 the station became known as Fairbank, in honor of Nathaniel Kellogg Fairbank, an investor in the New Mexico and Arizona Railroad and other railroad companies. New Mexico and Arizona timetables sometimes showed the name of the station as Fairbanks around the turn-of-the-century but eventually returned to the proper spelling, which the post office had used consistently since 1883. Merchants and other people moved into the area and a town came into existence there.

Work continued on the portion of the railroad that went westward in the Babocomari River area. The Arizona Weekly Citizen reported on January 22, 1882 (AWC, 1882a; TWE, 1882b) that the grading for that portion of the railroad would be completed within approximately six weeks and would span 35 miles from the junction with the San Pedro River. There had been considerable problems about the question of right of way. On January 20, 1882, a party of armed men stopped the work of both the pile drivers and graders near the mouth of the Babocomari River until the railroad arranged for a right-of-way. A board of Commissioners, formed to condemn lands needed by the railroad and to establish the price paid for such property, settled part or all the disputes by April 9, 1882 (AWC, 1882b). On October 25, 1882, the railroad held a ceremony in Nogales in which Mrs. Morley, wife of William R. Morley of the Sonora Railroad, and C. C. Wheeler, general manager of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad tapped into the ground a spike to connect the New Mexico and Arizona Railroad and the Sonora Limited Railroad (AWC, 1882c; Myrick, 1981, p. 282).

The trains along the railroad usually consisted of only a few cars (Myrick, 1981, p. 288). Freight traffic was mostly international in nature or associated with the local mines, but cattle shipments sometimes required two engines on special trains. Part of the reason for establishing the railroad was to enable the import and export of products to and from Arizona via the port of Guaymas. As of November 16, 1895, the through rate to Nogales and other points along the railroad via the Pacific Coast Steamship Co. to Nogales for straight carload lots of 24,000 pounds was $0.75 per 100 pounds to Nogales, and $1.00 per 100 pounds to Crittenden, Huachuca, and Fairbank (TE, 1895). For cargo smaller than a carload the rate from San Francisco to Fairbank was $1.71 per 100 pounds.

The railroad was not immune to the heavy rains that fell in some portions of southeastern Arizona during the latter part of the 19th century. Heavy rainfall in July 1887 caused such severe damage that it took several weeks of repairs before trains could again use the tracks (ACH, 1887; TE, 1887). The Arizona Champion reported the damage on July 23, and The Tombstone Epitaph wrote on August 20 that the trains were again running over the tracks. Flood damage to the railroad between Nogales and Benson was extensive enough in August 1890 that a group of Tucson citizens unsuccessfully attempted to induce the company to not repair the damage but rather to build the road from Calabasas to Tucson (AR, 1890).

People sometimes forgot, with unfortunate results, that trains and cars were potentially dangerous. A coroner’s jury reported on October 18, 1890 about the death of John McMahon (AWE, 1890). He and Frank Stares had traveled from Bisbee to Fairbank on foot and arrived in the latter town on the morning of October 17. They were tired and laid down to sleep near a sidetrack. McMahon evidently laid beneath a freight car. He was killed instantly when the heavy car was moved.

The railroad established passenger fair rates in 1882 of ten cents per mile from Benson to Nogales and three cents a mile from there to Guaymas (AS, 1882). Over time the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad became less interested in owning the New Mexico and Arizona railroad (Myrick, 1981, p. 288-289). On July 1, 1897, the Southern Pacific began managing the system, and on July 15, 1898 the Santa Fe leased the New Mexico and Arizona Railroad and the Sonora Limited Railroad to the Southern Pacific on a long-term basis, ending in 1979.

Literature Cited

AC. 1879a. For Sale or Rent, The Tres Alamos House [ad], p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. February 8, 1879. (PDF accessed July 20, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-02-08/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879b. Tucson & Tombstone Stage Line [ad], p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. March 14, 1879. PDF accessed June 10, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-03-14/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1880a. A. A. Wilt, Tres Alamos, Arizona, Dealer in General Merchandise [ad], p. 4. The Arizona Citizen. April 3, 1880. (PDF accessed August 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1880-04-03/ed-1/seq-4/).

AC. 1880b. San Pedro, p. 2. The Arizona Citizen. August 28, 1880. (PDF accessed July 15, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016240/1880-08-28/ed-1/seq-2/).

ACH. 1887. Territorial, p. 2. The Arizona Champion. July 23, 1887. (PDF accessed November 11, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016246/1887-07-23/ed-1/seq-2/).

Altshuler, C. W. 1980. The Southern Pacific Caper. The Journal of Arizona History. 21: 1-10.

AR. 1890. Want a Railroad, p. 2. The Arizona Republican. August 9, 1890. (PDF accessed November 11, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020558/1890-08-09/ed-1/seq-2/).

AS. 1877a. Arizona Sentinel, p. 3. September 29, 1877. (PDF accessed June 12, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1877-09-29/ed-1/seq-3/).

AS. 1877b. Completion of the Railroad Bridge–Strategy–The Cars in Arizona–The Army Defied–Enterprise or Crime?, p. 1. The Arizona Sentinel. October 6, 1877. (PDF accessed April 5, 2015 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1877-10-06/ed-1/seq-1/).

AS. 1881. Railroad Items, p. 1. The Arizona Sentinel. July 2, 1881. (PDF accessed November 6, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1881-07-02/ed-1/seq-1/).

AS. 1882. Territorial, p. 1. The Arizona Sentinel. November 25, 1882. (PDF accessed November 11, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1882-11-25/ed-1/seq-1/).

ATS. 1880. Arizona Her Great Mining Agricultural, Stock-raising & Lumber Interests. The Only Direct Route Via the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe R. R. 5 p. [advertising circular]. (PDF accessed June 7, 2014 at https://uair.arizona.edu/item/293476).

AWC. 1882a. New Mexico and Arizona Railroad, p. 3. The Arizona Weekly Citizen. January 22, 1882. (PDF accessed November 6, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-01-22/ed-1/seq-3/).

AWC. 1882b. Right of Way, p. 4. The Arizona Weekly Citizen. April 9, 1882. (PDF accessed November 8, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-04-09/ed-1/seq-4/).

AWC. 1882c. Telegraph. Pacific Coast, p. 1. The Arizona Weekly Citizen. October 29, 1882. (PDF accessed November 9, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-10-29/ed-1/seq-1/).

AWE. 1890. Mangled by the Cars, p. 3. The Arizona Weekly Enterprise. October 25, 1890. (PDF accessed November 11, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-10-25/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

Best, G. M. 1941. The Southern Pacific Company. The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, Locomotives of the Southern Pacific Company. August, 1941: 5-13.

CC. 1886. The Clifton Clarion, p. 3. September 22, 1886. (PDF accessed July 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94050557/1886-09-22/ed-1/seq-3/).

Coman, E. T., Jr. 1942. Sidelights on the Investment Policies of Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, and Crocker. Bulletin of the Business Historical Society. 16: 85-89.

Elliott, W. E. [Publisher]. 1884. History of Arizona Territory, Showing Its Resources and Advantages; with Illustrations Descriptive of Its Scenery, Residences, Farms, Mines, Mills, Hotels, Business Houses, Schools, Churches, etc. from Original Drawings. Wallace W. Elliott & Co., Publishers, San Francisco. (PDF accessed June 7, 2014 at https://uair.arizona.edu/item/293664).

McCrary, G. W. 1878. Location of Southern Pacific and Texas Pacific Railroads. Letter from the Secretary of War Concerning the Location of the Southern Pacific and Texas Pacific Railroads through fort Yuma Reservation and across the Colorado River. January 21, 1878.–Referred to the Committee on the Pacific Railroad and Ordered to be Printed, 45th Congress, 2d Session. House of Representatives. Ex. Doc. No. 33, p. 1-34, 992-1027 abs. In Index to the Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-fifth Congress 1877-’78. In 22 Volumes. Volume X.–No. 1, Pts. 6, 7, 8, and Nos. 7 to 33 inclusive. Government Printing Office, Washington. 1035 p. [Documents & reports individually paginated] (PDF accessed June 10, 2016 at https://books.google.com/books?id=NJ8FAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA8-PA21&lpg=RA8-PA21&dq=I+have+telegraphed+commanding+officer+fort+Yuma+to+order+the+company&source=bl&ots=wdf05lhJgX&sig=b_XOhwCtBrFqkp6UIP12SLcBXUI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiNwcKa1p7NAhVS6mMKHcqGAf8Q6AEIHjAA#v=onepage&q=I%20have%20telegraphed%20commanding%20officer%20fort%20Yuma%20to%20order%20the%20company&f=false).

Myrick, D. F. 1981. Railroads of Arizona vol. 1: The Southern Roads. Second Printing. Howell-North Books, San Diego. 477 p.

Sayre, N. F. 1999. The cattle boom in southern Arizona: towards a critical political ecology. Journal of the Southwest, 41: 239-271). (PDF accessed June 11, 2014 at http://geography.berkeley.edu/documents/sayre/sayre_1999_cattle_boom.pdf).

Summerhayes, M. 1911. Vanished Arizona: Recollections of the Army Life of a New England Woman. The Salem Press Co., Salem, Mass. 319 p. (PDF accessed June 10, 2016 at https://books.google.com/books/download/Vanished_Arizona.pdf?id=hukTAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&capid=AFLRE72M8I5-l3RAnhLFjKlY4Ryzx2FT7V5x0M8s31SXvav4GEJCT3TnFFG3ixTu7-ywA6twT_TwEJpBzBuCizOW7c8awEcj6A&continue=https://books.google.com/books/download/Vanished_Arizona.pdf%3Fid%3DhukTAAAAYAAJ%26output%3Dpdf%26hl%3Den).

TE. 1882. Local Splinters, p. 3. The Tombstone Epitaph. February 20, 1882. (PDF accessed November 8, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-02-20/ed-1/seq-3/).

TE. 1887. Local Happenings & Mining Matters, p. 3. The Tombstone Epitaph. August 20, 1887. (PDF accessed November 11, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1887-08-20/ed-1/seq-3/).

TE. 1895. The Tombstone Epitaph, p. 2. (PDF accessed November 12, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1895-11-17/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

TT. 1885. Agricultural. A Review of the Various Ranches. The Land Adjoining the San Pedro from Fairbank to Redington Blooming like a Rose–Cattle and Horses by the Score are to be seen, p. 6. The Tombstone. July 20, 1885. (PDF accessed August 17, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn96060683/1885-07-20/ed-1/seq-6/).

TWE. 1882a. By Special Train, p. 1. The Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. January 16, 1882. (PDF accessed November 6, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-01-16/ed-1/seq-1/).

TWE. 1882b. New Mexico and Arizona Railroad, p. 3. The Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. January 23, 1882. (PDF accessed November 8, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-01-23/ed-1/seq-3/).