Stagecoach Lines

Racing for the gold. Stagecoach lines in and around the San Pedro valley after the Civil War.

Gerald R Noonan PhD

(Excerpt from book manuscript about the human and environmental history of the San Pedro River Valley and adjacent areas from the Gadsden purchase to statehood. Text © Gerald R Noonan PhD)

Gerald R Noonan PhD

(Excerpt from book manuscript about the human and environmental history of the San Pedro River Valley and adjacent areas from the Gadsden purchase to statehood. Text © Gerald R Noonan PhD)

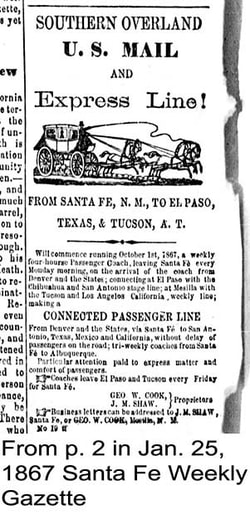

The first stage line to regularly cross the San Pedro Valley after the Civil War was the Tucson and Los Angeles California weekly line (ANSAC, 2006, p. IV-64; SFWG, 1867, 1869) that followed the former Butterfield Overland Mail route in Arizona beginning October 1, 1867. The coaches from Tucson linked in Mesilla, New Mexico, with the Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line, and the latter line offered service to El Paso and Santa Fe.

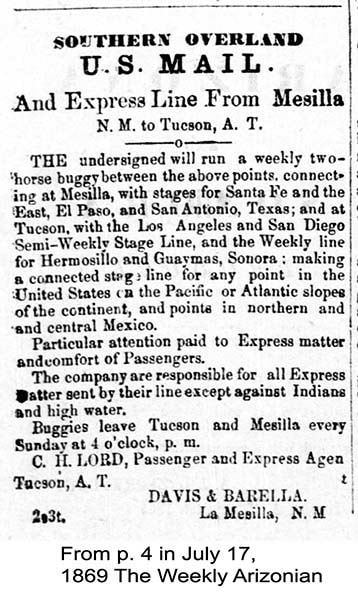

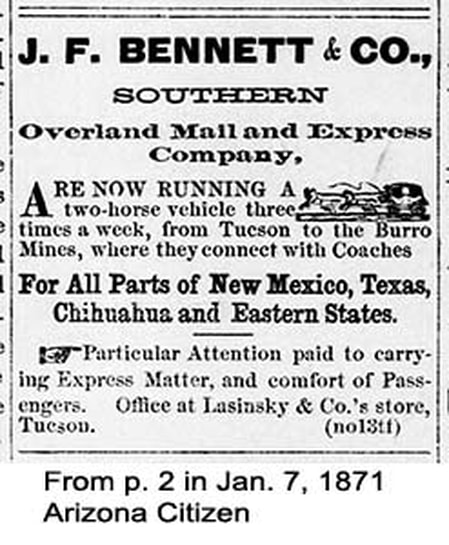

On July 17, 1869 the Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line from Mesilla (WA, 1869) replaced the Southern Overland line and began offering a weekly “two-horse buggy” or buckboard between Tucson and Mesilla. It connected at Mesilla with stages for Santa Fe and the East, El Paso, and San Antonio, and linked at Tucson with the Los Angeles and San Diego Semi-Weekly Stage Line and the weekly line for Hermosillo and Guaymas. In 1870 the owners sold their company to J. F. Bennett and Company (Thrapp, 1988a, p. 380). The latter company (PSB, 1907, p 730-731) also followed the route of the former Butterfield Overland Mail and Express Co., extending from Mesilla, New Mexico, crossing the Rio Mimbres at Mowry City (area with several mines), and reaching to Tucson. The company advertised its transportation service from Tucson to New Mexico until June 27, 1874 (AC, 1871, 1874c).

On July 17, 1869 the Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line from Mesilla (WA, 1869) replaced the Southern Overland line and began offering a weekly “two-horse buggy” or buckboard between Tucson and Mesilla. It connected at Mesilla with stages for Santa Fe and the East, El Paso, and San Antonio, and linked at Tucson with the Los Angeles and San Diego Semi-Weekly Stage Line and the weekly line for Hermosillo and Guaymas. In 1870 the owners sold their company to J. F. Bennett and Company (Thrapp, 1988a, p. 380). The latter company (PSB, 1907, p 730-731) also followed the route of the former Butterfield Overland Mail and Express Co., extending from Mesilla, New Mexico, crossing the Rio Mimbres at Mowry City (area with several mines), and reaching to Tucson. The company advertised its transportation service from Tucson to New Mexico until June 27, 1874 (AC, 1871, 1874c).

In 1874 the Kerens and Mitchell Company established the Southern Pacific Mail Stage Line between San Diego and Mesilla, New Mexico, via the old Butterfield Overland Mail route (Peterson, 1968). This well-stocked line (Hinton, 1878, p. 371-372, 416-417 abs.; Hodge, 1877, p. 204) had 650 horses, 37 coaches and stages, and 47 drivers and 104 stock-tenders. It claimed then to be the longest stage line in the United States, extending from Yuma to Mesilla and connecting there with another stage line for Austin and other places in Texas. Travel between San Diego and Mesilla took eight days. The company soon lost its California business as the Southern Pacific railroad advanced eastward, but in 1878 the Kearns and Griffith Company, an outgrowth of the previous firm, began stage service eastward from Yuma until the advancing railroad made such service obsolete.

Stage service through and within the San Pedro Valley improved on March 20, 1878 when J. T. Chidester contracted with the postmaster to transport mail from Fort Worth Texas to Yuma and back seven times a week (SC, 1890, p. 2, 519 abs.; 19, 536 abs.; 64, 581 abs.; 73, 590 abs.; 106, 623 abs.; 148, 665 abs.; 169, 686 abs.). In the San Pedro Valley, the route detoured from that of the Overland Mail Company by going north to Tres Alamos and then onward to Tucson. Every other day Chidester’s National Mail and Transportation Company sent out four-horse coaches from Mesilla to Tucson and on alternate days had horseback service between Mesilla and Silver City and buckboard service from Silver City to Tucson. Maintaining the mail and passenger service between Mesilla and Tucson required about 160 head of horses and mules and 34 men. The company kept 16 horses or mules at the San Pedro Station (former station of Butterfield Overland Mail, located at Middle Crossing near current day Benson; the crossing area in common parlance was called San Pedro Crossing or simply San Pedro). On September 20, 1880 the company curtailed service and went no further west than Benson, transferring westbound mail to the railroad there. After the arrival of the railroad at Benson, it used a single buckboard to provide service between Benson and Tres Alamos.

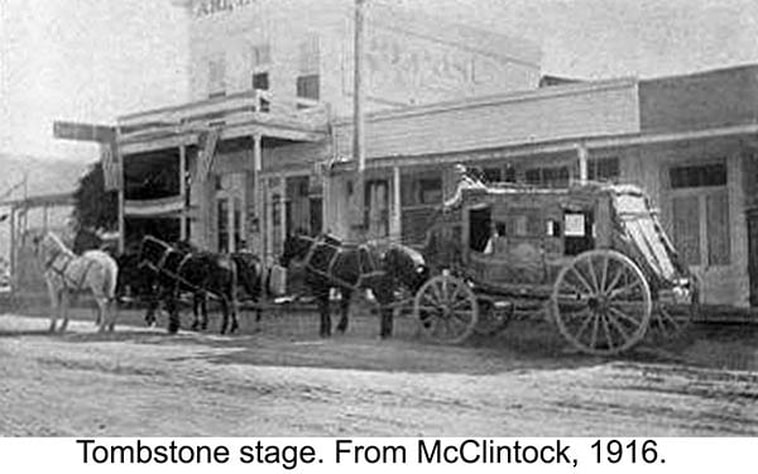

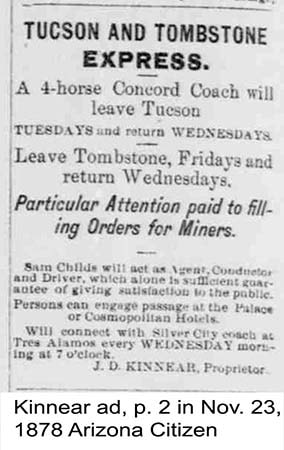

The discovery of silver and other minerals in the Tombstone area created an increasing market for stage lines. John Delamore Kinnear at the age of 38 years reached Tucson on October 18, 1878 and within a month of his arrival had investigated the then 95-mile route that went to Tombstone via Tres Alamos and returned by a shorter more southern route (Peterson, 1968). In 1878 and early 1879 Kinnear’s stage line left Tucson in the morning and arrived at the old Butterfield station at Cienega (now known as Pantano. Barnes, 1988, p. 316) at lunchtime. The stage then headed around the southern end of the Rincon Mountains and went northwards to the Lower Crossing at Tres Alamos. Passengers spent the night at a ranch, and the next morning the stage crossed the San Pedro and headed southward toward Tombstone.

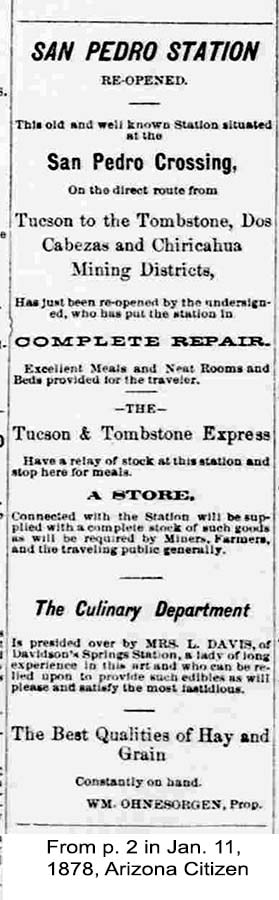

Kinnear realized in March 1879 that an increasing proportion of passengers wanted to reach Tombstone as fast as possible. Therefore, he dropped Tres Alamos from his route between Tucson and Tombstone and offered a $10 fare for a trip that took only 17 hours (AC, 1879a). Residents along the middle and lower San Pedro River may have been without mail or passenger service until January 11, 1890 when R. T. Bolen’s two-horse buckboard service carried mail and passengers twice a week from Riverside to Benson (AC, 1879f; AWE, 1890a). The buckboard left each place on Monday and Thursdays and arrived at each destination Tuesday and Friday evenings. The route ran up the Gila and San Pedro rivers via Dudleyville, the Mammoth mine, Redington, and Tres Alamos. Passengers and mail could then connect with the Tucson and Tombstone line at Ohnesorgen’s place at the San Pedro Station.

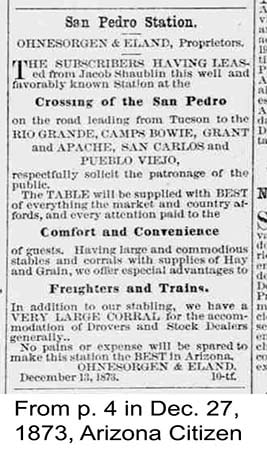

The increasing number of people traveling by stage created business opportunities for entrepreneurs to provide services to travelers and to star their own transportation businesses. One such man was William Ohnesorgen (Bailey and Chaput, 2000, p. 48-50; Chapman, 1901, p. 968, 970 abs.). He had moved from Tucson to the San Pedro Crossing in 1871 and there kept a government forage agency and supplied US troops with provisions until approximately the placement of the Apaches onto reservations. In December, 1873 he and Frederick Eland leased the San Pedro Station at the Middle Crossing of the San Pedro, in the region of current day Benson (AC, 1873; Langley, 1875, p. 783, 905 abs.). The partners promised the “BEST of everything the market and country affords” as regards meals and boasted of large stables and corrals and supplies of hay and grain. The partners purchased the station in early March 1874 and by May 1874 had added a bar to it (AC, 1874a; AC, 1874b). Ohnesorgen and Eland dissolved their partnership on February 6, 1875, and Ohnesorgen assumed all liabilities of their late firm and gave notice that he would continue to carry on the business (AC, 1875). On November 10, 1887 he obtained title to 160 acres just east of Benson in Township 17E Range 20E, Section 11, Aliquot NW¼ (AC, 1877; BLM, 2015) and on February 19, 1891 he gained title to another 160 acres in Township 17E Range 20E, Section 2 Aliquot SW¼. The San Pedro River flowed through these adjoining aliquots (USGS, 1915). Ohnesorgen raised cattle and for a time sheep on his ranch (Peterson, 1968). By 1879 he had experience supplying army troops with forage and provisions and stage lines and freighting teams with hay and grain. His station was a welcome stop for travelers.

Stage service through and within the San Pedro Valley improved on March 20, 1878 when J. T. Chidester contracted with the postmaster to transport mail from Fort Worth Texas to Yuma and back seven times a week (SC, 1890, p. 2, 519 abs.; 19, 536 abs.; 64, 581 abs.; 73, 590 abs.; 106, 623 abs.; 148, 665 abs.; 169, 686 abs.). In the San Pedro Valley, the route detoured from that of the Overland Mail Company by going north to Tres Alamos and then onward to Tucson. Every other day Chidester’s National Mail and Transportation Company sent out four-horse coaches from Mesilla to Tucson and on alternate days had horseback service between Mesilla and Silver City and buckboard service from Silver City to Tucson. Maintaining the mail and passenger service between Mesilla and Tucson required about 160 head of horses and mules and 34 men. The company kept 16 horses or mules at the San Pedro Station (former station of Butterfield Overland Mail, located at Middle Crossing near current day Benson; the crossing area in common parlance was called San Pedro Crossing or simply San Pedro). On September 20, 1880 the company curtailed service and went no further west than Benson, transferring westbound mail to the railroad there. After the arrival of the railroad at Benson, it used a single buckboard to provide service between Benson and Tres Alamos.

The discovery of silver and other minerals in the Tombstone area created an increasing market for stage lines. John Delamore Kinnear at the age of 38 years reached Tucson on October 18, 1878 and within a month of his arrival had investigated the then 95-mile route that went to Tombstone via Tres Alamos and returned by a shorter more southern route (Peterson, 1968). In 1878 and early 1879 Kinnear’s stage line left Tucson in the morning and arrived at the old Butterfield station at Cienega (now known as Pantano. Barnes, 1988, p. 316) at lunchtime. The stage then headed around the southern end of the Rincon Mountains and went northwards to the Lower Crossing at Tres Alamos. Passengers spent the night at a ranch, and the next morning the stage crossed the San Pedro and headed southward toward Tombstone.

Kinnear realized in March 1879 that an increasing proportion of passengers wanted to reach Tombstone as fast as possible. Therefore, he dropped Tres Alamos from his route between Tucson and Tombstone and offered a $10 fare for a trip that took only 17 hours (AC, 1879a). Residents along the middle and lower San Pedro River may have been without mail or passenger service until January 11, 1890 when R. T. Bolen’s two-horse buckboard service carried mail and passengers twice a week from Riverside to Benson (AC, 1879f; AWE, 1890a). The buckboard left each place on Monday and Thursdays and arrived at each destination Tuesday and Friday evenings. The route ran up the Gila and San Pedro rivers via Dudleyville, the Mammoth mine, Redington, and Tres Alamos. Passengers and mail could then connect with the Tucson and Tombstone line at Ohnesorgen’s place at the San Pedro Station.

The increasing number of people traveling by stage created business opportunities for entrepreneurs to provide services to travelers and to star their own transportation businesses. One such man was William Ohnesorgen (Bailey and Chaput, 2000, p. 48-50; Chapman, 1901, p. 968, 970 abs.). He had moved from Tucson to the San Pedro Crossing in 1871 and there kept a government forage agency and supplied US troops with provisions until approximately the placement of the Apaches onto reservations. In December, 1873 he and Frederick Eland leased the San Pedro Station at the Middle Crossing of the San Pedro, in the region of current day Benson (AC, 1873; Langley, 1875, p. 783, 905 abs.). The partners promised the “BEST of everything the market and country affords” as regards meals and boasted of large stables and corrals and supplies of hay and grain. The partners purchased the station in early March 1874 and by May 1874 had added a bar to it (AC, 1874a; AC, 1874b). Ohnesorgen and Eland dissolved their partnership on February 6, 1875, and Ohnesorgen assumed all liabilities of their late firm and gave notice that he would continue to carry on the business (AC, 1875). On November 10, 1887 he obtained title to 160 acres just east of Benson in Township 17E Range 20E, Section 11, Aliquot NW¼ (AC, 1877; BLM, 2015) and on February 19, 1891 he gained title to another 160 acres in Township 17E Range 20E, Section 2 Aliquot SW¼. The San Pedro River flowed through these adjoining aliquots (USGS, 1915). Ohnesorgen raised cattle and for a time sheep on his ranch (Peterson, 1968). By 1879 he had experience supplying army troops with forage and provisions and stage lines and freighting teams with hay and grain. His station was a welcome stop for travelers.

On August 15, 1879 Ohnesorgen advertised (AC, 1879b) that he had completed “a good and substantial bridge across the San Pedro River, at San Pedro Station, A. T., at his own expense, and will, therefore, collect toll from those using it until he is reimbursed.” The sturdy bridge, in the region of current day Benson, cost Ohnesorgen $900 and almost immediately attracted wagons carrying 20 tons of cargo (AC, 1879c).

A second transportation entrepreneur appeared in the form of Howard C. Walker, a 27-year-old “dandy” who had been living in Tucson with three young female housekeepers and worked for Kinnear (Peterson, 1968). He quit his job with Kinnear and on September 13, 1879 Ohnesorgen and Walker formed a partnership to establish a stage line between Tucson and the Tombstone Mining District.

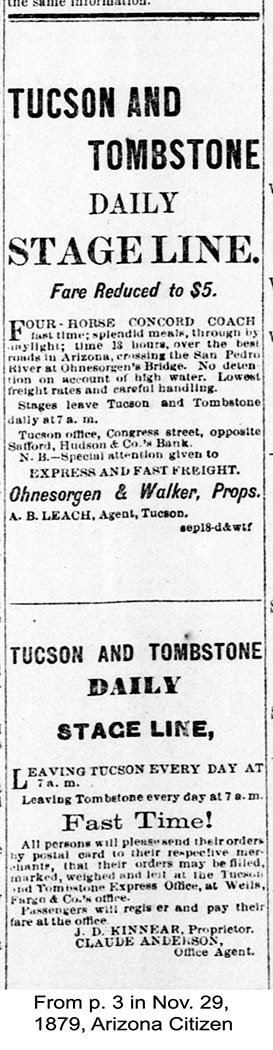

A September 25, 1879 ad in the Arizona Star announced the new stage line (Peterson, 1968) and was followed two days later by a September 27, 1879 ad in The Arizona Citizen (AC, 1879d).

The two stage companies completed by lowering fares and attempting to each offer the fastest transit between Tombstone and Tucson (Peterson, 1968). Kinnear’s stages took a new road via Ash Spring where he had built a station at the north end of the Whetstone Mountains. The new route provided a shorter travel distance by going southeast from the station and crossing the San Pedro at the Upper Crossing near current day St. David.

Ohnesorgen and Walker took a route via Ohnesorgen’s bridge and advertised that the use of the bridge prevented delays because of high water. The rival companies struggled to be first to arrive in town but neither could establish a record of consistently being the fastest. Ohnesorgen and Walker had 400 posters printed about the new stage line and distributed and displayed these along the entire route. Walker subsequently complained that a vandal had apparently defaced and torn down most of the 400 posters put up along the route of his company and offered a reward of $10 for the arrest and conviction of the vandal.

The rival companies established somewhat of a brief truce in September and October 1879 by agreeing that Ohnesorgen and Walker stages would leave Tucson on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays and depart from Tombstone on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. In turn Kinnear’s line left Tucson on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and went from Tombstone on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The new schedules gave customers daily service between the two towns and temporarily halted the races.

Because travel to the Tombstone District continued to increase, Kinnear began offering daily service on his stage line at the end of October and in November 1879 reduced his freight rates from 5 to 3 cents a pound. He contracted with the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company and the Corbin and Gird Mills to carry their valuable ingots on his stage coaches. Kinnear had previously refused this dangerous cargo because of fear of robberies, and the miners had been forced to haul the heavy bars on wagons that bristled with guards who protected shipments as valuable as $30,000–$734,000.00 in 2014 purchasing power after adjustment for inflation (MW, 2016).

Ohnesorgen and Walker responded by adding a new coach to their line and by beginning daily runs on November 10. They reported a number of sabotages during the period of intense competition, four horses poisoned in Tucson, four mules and two horses strayed or stolen, and an axle nut removed from the stage. Both companies switched to six horse teams to make faster times and began the races anew.

During a new price war Kinnear lowered his fare to $4 each way and his freight rates to 1 ½ cents per pound. As part of a public relations campaign, he gathered an exhibit of minerals from Arizona mines and put them on free public display in his Tucson office. Finally, he lowered one-way fares to only $3 in mid-December.

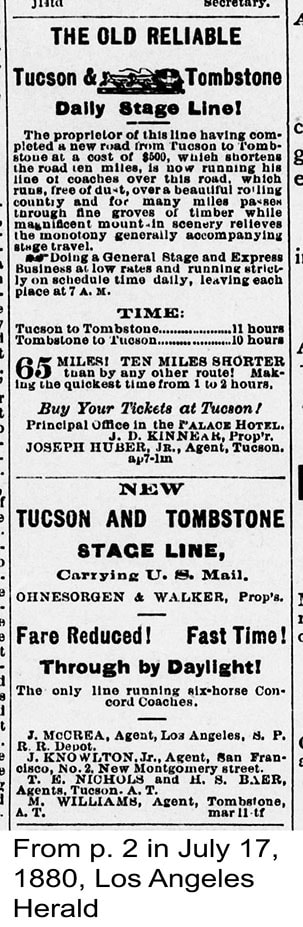

In November 1879 Ohnesorgen and Walker reduced one-way stage fares to $5 (AC, 1879e). The next month they convinced the Tombstone and Corbin mill and mining companies to discontinue their two-month-old contract with Kinnear and transfer their bullion carrier needs to Ohnesorgen and Walker’s stage line (Peterson, 1968). They also established an agency in Los Angeles to promote their stage line to customers who boarded the Southern Pacific railroad that was bringing ever larger numbers of people into southern Arizona and was steadily laying track eastward toward Tucson. The partners also countered Kinnear’s fares by lowering theirs to only $3 each way.

Both companies lost money during the trade wars, and Ohnesorgen had to mortgage his ranch for $3000 to recoup losses and stay in business. On Christmas day 1879 the rivals met and agreed on a compromise that set fares at $7 each way and freight at three cents a pound. The competition between the companies continued as each attempted to attract business by making the speediest trip, performing publicity stunts, and advertising.

Competition to be the fastest to cover a given route was frequent between the various stage companies. Horses sometimes suffered because owners were willing to run them to the point of exhaustion to save time. George Parsons wrote in his diary about his 1880 arrival in Tombstone by Ohnesorgen and Walker stage (Parsons, 1996, p. 17-18). The stage company changed horses and driver at Ohnesorgen’s at the San Pedro Crossing. The new driver was under orders to beat the opposition stage and had to treat the six horses cruelly to speed along as fast as possible for 16 miles to Contention Mills in an hour and a half. “Horses on dead jump all of the time and nearly dead when we arrived at C. afraid one leader will die. Uphill and down on dead run. Fine for us but death to horses.”

Mail service between Tucson and Tombstone deteriorated when an eastern mail speculator, Edward Gannon, obtained a federal contract beginning October 1, 1879 to carry the mail (Parsons, 1996, p. 21; Peterson, 1968; US, 1881, p. 65, 76 abs.). Gannon set up a stage line to carry the mail along the federal route of 40108. The circuitous route passed through the Empire Ranch, Camp Huachuca, and Charleston. People wondered how the new line would deliver the mail on schedule given that the annual contract for the route was only $849. Residents in Tucson and Tombstone found that the new vendor delivered the mail six hours behind schedule and 12 hours later than Kinnear had previously delivered it. After several months of public complaints, Gannon stopped carrying the mail. James Stewart temporarily took over the route but discontinued service after receiving no response from the post office to his attempts to negotiate a contract. The post office then sent an agent to Tombstone, Charleston, Camp Huachuca, and Patagonia and on February 21, 1880 the post office awarded a contract to Howard C. Walker of Ohnesorgen & Walker to carry mail daily to Tombstone and three times a week to Huachuca via Tombstone and Charleston (AC, 1880). Ohnesorgen and Walker inaugurated their carrying of the mail by decorating a stagecoach with American flags and telling the driver to beat the opposition at all costs. Late on February 22, 1880 the mud spattered stage came in to Tucson at full run, just ahead of Kinnear’s (Parsons, 1996, p 21).

The approach of the Southern Pacific railroad toward Tucson in early 1880 showed that stage business along railroad routes would progressively decrease (Peterson, 1968). Ohnesorgen quit the stage business and sold his interest to Walker on March 9, 1880. The H. C. Walker & Co. ran the new Tucson & Tombstone Daily U.S. Mail Line after the dissolution of the partnership. It became the foremost stage line in the area and carried passengers, mail and bullion from the Tombstone mines. Walker resolved to stay in the stage line business and in March 1880 purchased all of the stock and coaches of the Griffith Southern Pacific Stage Line whose route had been reduced as the railroad moved ever eastward. By late April the Southern Pacific had reached Pantano, and Kinnear and Walker’s stage lines had a reduced route between there and Tombstone.

In early 1880 Walker expanded his company by providing stage service from Tucson to Patagonia, Harshaw, and the new Washington Camp and purchased a substantial building in Contention City to house a stage office that previously had been in a temporary tent (Peterson, 1968). He renamed his company on April 24, 1882 as Arizona Mail and Stage Company, borrowing $2500 from Tucson merchant Sam Hughes to help finance the expansion.

After the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Benson in June 1880, the stage run from there to Tombstone was only 24 miles (Peterson, 1968). Kinnear and Walker decided to collaborate to make things easier for themselves and make more money. Although the trains reached Benson between three and four a.m., the companies made no attempt to accommodate Tombstone-bound passengers until much later in the morning. They raised freight rates to five cents per pound and passenger fares to what was then an exorbitant charge of $10 for the 25-mile trip. They slowed down their coaches so that the trip took nearly twice as long as before. The former rivals then combined their companies into the Arizona Mail & Stage Company. For a short while Walker seemed to be the dominant partner. His large six-horse coaches carried all of the passengers, the mail, and the Wells Fargo box of cash and valuables. Kinnear’s coach followed along with express material and heavy freight.

Riding a stagecoach was not an especially enjoyable experience (Faulk, 1972, p 83-84). John Pleasant Gray rode a Kinnear and Walker Concord coach from Pantano to Tombstone in 1880 and stated:

"That day’s stage ride will always live in my memory–but not for its beauty spots. Jammed like sardines on the hard seats of an old time leather spring coach–a Concord–leaving Pantano, creeping much of the way, letting the horses walk, through miles of alkali dust that the wheels rolled up in thick clouds of which we receive the full benefit, we couldn’t then see much romance in the old stage method of traveling. . . . If it had not been for the long stretches when the horses had to walk, enabling most of us to get out and ‘foot it’ as a relaxation, it seems as if we could never have survived the trip."

New competition with the Kinnear-Walker monopoly on the line between Benson and Tombstone emerged when Robert Crouch, popularly known as “Sandy Bob,” formed an “opposition” line and on June 21, 1880 began carrying passengers between Benson and Tombstone (Peterson, 1968). On July 26, 1880 W. R. Ingram’s Tucson and Patagonia Stage Company also began daily service between Benson and Tombstone for $3 from Tombstone to Benson and three dollars and 50 cents from Benson to Tombstone (WAC, 1880). The company also offered service three times a week between Tombstone and Harshaw (mining camp about eight miles SE of Patagonia) for a fare of $6.00 each way.

Walker’s status as a senior partner within the Arizona Mail & Stage Company soon changed (Peterson, 1968). After Walker returned from a trip to San Francisco to purchase new stock, Kinnear demanded management changes. Kinnear had invested $3500 in the combined company but had not previously acted as an equal partner. Walker still owed Sam Hughes $2500 and had taken on additional debts when he purchased two carloads of new horses in San Francisco. Walker signed an agreement whereby he would receive a salary of $150 per month and Kinnear would take possession of the company’s coaches, stock, and other property in Benson, Tombstone and Harshaw. Kinnear would run the company and retain all profits until his investment had been paid off with interest. In November 1880 Walker became vice president and general superintendent for the combined line that Kinnear ran. However, in approximately 1881 Walker turned over to Kinnear his remaining interests in the Arizona Mail & Stage Company.

Kinnear reorganized some company operations and worked to eliminate a new arrival, Weston Ingram (Peterson, 1968). He agreed that his company would withdraw its competitive line on the Pantano to Harshaw route if Ingram’s Tucson and Patagonia Mail and stage Company halted its opposition runs between Benson and Tombstone. In October 1880 each company carried out the terms of the agreement and secured nearly a virtual monopoly on stage service within its own territory. Kinnear and Walker on November 20, 1880 obtained a contract for carrying mail to and from Bisbee. The Arizona Mail & Stage Company started running stages three times a week from Charleston to Bisbee.

Despite Kinnear’s best efforts the company faced increasing competition (Peterson, 1968). In December 1880 N. Smith’s Fast Freight and Passenger Line began offering stiff competition by charging only $2.50 for passage from Benson to Tombstone and at times charging only $1.00 or $2.00. When miners began to migrate to new mines in Mexico, Chester W. Pinkham established a Tombstone and Sonora Stage Line that provided weekly service along a route that traveled south from Tombstone and into Mexico.

Kinnear became tired of running a network of stage lines and on November 29, 1881 sold most of his line to William W. Hubbard and William D. Crow (Peterson, 1968). The $3800 sale included 20 horses equipped each with a harness, a coach called “Nelly Boyd,” a nine passenger coach, a “jerky” (light two-seat “with canvas top, capable of carrying 4-5 passengers), a spring wagon, and assorted curry combs and brushes. The new W. W. Hubbard & Company began running coaches three times a week to Bisbee and daily to Fort Huachuca. Kinnear continued making daily trips to Contention and Benson. In March 1882 Kinnear stages left Tombstone for Contention at 5 a.m. to connect with eastbound trains and departed from Tombstone at 12:20 PM to connect with westbound trains (TE, 1882a). The fares were (figures in parentheses are converted to 2014 dollars adjusted for inflation at the MW, 2015, site) $1.25 ($29.90) to Charleston, $1.50 ($35.80) to Contention, $3.50 ($83.60) to Hereford or Huachuca, and $6 ($143) to Bisbee.

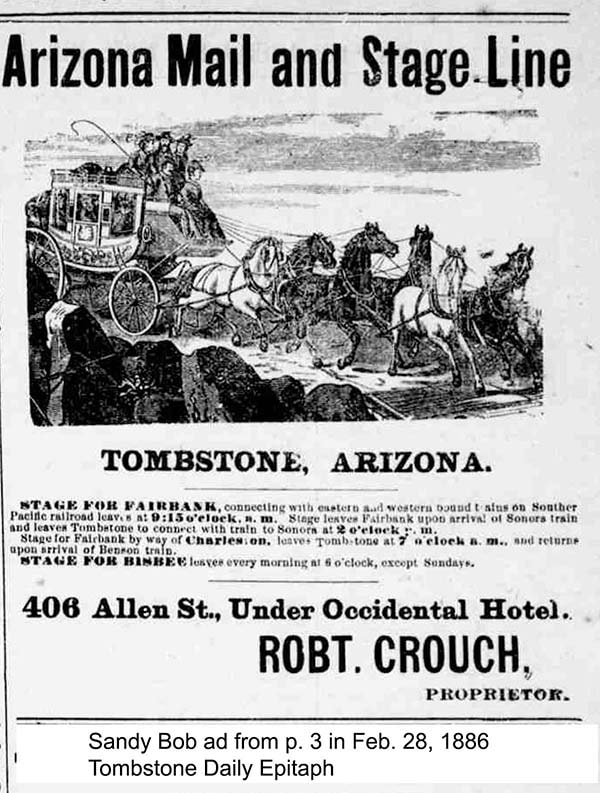

Economic problems in the Tombstone area apparently made Kinnear think about leaving the stage business. On June 3, 1882 he advertised for sale in the Tombstone Epitaph (TE, 1882b) a 17-passenger Concord Coach, two 17-passenger Concord Mud Wagons, two 11-passenger Concord Mud Wagons, and one 9-passenger Concord Mud Wagon. He apparently was unable to sell these items and entered into an arrangement with Robert Crouch, popularly known as Sandy Bob, who was the Tombstone business manager for the Arizona Stage and Mail Company (Cobler, 1883, p. 147, 162 abs.)

Crouch was not discouraged by the Tombstone depression and in June 1882 added an extra two-horse mud wagon on the road to Contention City to meet competition from Newton Smith (Peterson, 1968). Smith subsequently went out of business in the last week of September 1882. Early in July 1882 Crouch and Kinnear purchased property in Charleston for a new and larger office and by August the Arizona Mail and Stage Company again was offering daily coaches to Charleston and Huachuca, offering service three times a week to Hereford and Bisbee, and providing transportation to the railroad at Contention City.

Ohnesorgen and Walker responded by adding a new coach to their line and by beginning daily runs on November 10. They reported a number of sabotages during the period of intense competition, four horses poisoned in Tucson, four mules and two horses strayed or stolen, and an axle nut removed from the stage. Both companies switched to six horse teams to make faster times and began the races anew.

During a new price war Kinnear lowered his fare to $4 each way and his freight rates to 1 ½ cents per pound. As part of a public relations campaign, he gathered an exhibit of minerals from Arizona mines and put them on free public display in his Tucson office. Finally, he lowered one-way fares to only $3 in mid-December.

In November 1879 Ohnesorgen and Walker reduced one-way stage fares to $5 (AC, 1879e). The next month they convinced the Tombstone and Corbin mill and mining companies to discontinue their two-month-old contract with Kinnear and transfer their bullion carrier needs to Ohnesorgen and Walker’s stage line (Peterson, 1968). They also established an agency in Los Angeles to promote their stage line to customers who boarded the Southern Pacific railroad that was bringing ever larger numbers of people into southern Arizona and was steadily laying track eastward toward Tucson. The partners also countered Kinnear’s fares by lowering theirs to only $3 each way.

Both companies lost money during the trade wars, and Ohnesorgen had to mortgage his ranch for $3000 to recoup losses and stay in business. On Christmas day 1879 the rivals met and agreed on a compromise that set fares at $7 each way and freight at three cents a pound. The competition between the companies continued as each attempted to attract business by making the speediest trip, performing publicity stunts, and advertising.

Competition to be the fastest to cover a given route was frequent between the various stage companies. Horses sometimes suffered because owners were willing to run them to the point of exhaustion to save time. George Parsons wrote in his diary about his 1880 arrival in Tombstone by Ohnesorgen and Walker stage (Parsons, 1996, p. 17-18). The stage company changed horses and driver at Ohnesorgen’s at the San Pedro Crossing. The new driver was under orders to beat the opposition stage and had to treat the six horses cruelly to speed along as fast as possible for 16 miles to Contention Mills in an hour and a half. “Horses on dead jump all of the time and nearly dead when we arrived at C. afraid one leader will die. Uphill and down on dead run. Fine for us but death to horses.”

Mail service between Tucson and Tombstone deteriorated when an eastern mail speculator, Edward Gannon, obtained a federal contract beginning October 1, 1879 to carry the mail (Parsons, 1996, p. 21; Peterson, 1968; US, 1881, p. 65, 76 abs.). Gannon set up a stage line to carry the mail along the federal route of 40108. The circuitous route passed through the Empire Ranch, Camp Huachuca, and Charleston. People wondered how the new line would deliver the mail on schedule given that the annual contract for the route was only $849. Residents in Tucson and Tombstone found that the new vendor delivered the mail six hours behind schedule and 12 hours later than Kinnear had previously delivered it. After several months of public complaints, Gannon stopped carrying the mail. James Stewart temporarily took over the route but discontinued service after receiving no response from the post office to his attempts to negotiate a contract. The post office then sent an agent to Tombstone, Charleston, Camp Huachuca, and Patagonia and on February 21, 1880 the post office awarded a contract to Howard C. Walker of Ohnesorgen & Walker to carry mail daily to Tombstone and three times a week to Huachuca via Tombstone and Charleston (AC, 1880). Ohnesorgen and Walker inaugurated their carrying of the mail by decorating a stagecoach with American flags and telling the driver to beat the opposition at all costs. Late on February 22, 1880 the mud spattered stage came in to Tucson at full run, just ahead of Kinnear’s (Parsons, 1996, p 21).

The approach of the Southern Pacific railroad toward Tucson in early 1880 showed that stage business along railroad routes would progressively decrease (Peterson, 1968). Ohnesorgen quit the stage business and sold his interest to Walker on March 9, 1880. The H. C. Walker & Co. ran the new Tucson & Tombstone Daily U.S. Mail Line after the dissolution of the partnership. It became the foremost stage line in the area and carried passengers, mail and bullion from the Tombstone mines. Walker resolved to stay in the stage line business and in March 1880 purchased all of the stock and coaches of the Griffith Southern Pacific Stage Line whose route had been reduced as the railroad moved ever eastward. By late April the Southern Pacific had reached Pantano, and Kinnear and Walker’s stage lines had a reduced route between there and Tombstone.

In early 1880 Walker expanded his company by providing stage service from Tucson to Patagonia, Harshaw, and the new Washington Camp and purchased a substantial building in Contention City to house a stage office that previously had been in a temporary tent (Peterson, 1968). He renamed his company on April 24, 1882 as Arizona Mail and Stage Company, borrowing $2500 from Tucson merchant Sam Hughes to help finance the expansion.

After the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Benson in June 1880, the stage run from there to Tombstone was only 24 miles (Peterson, 1968). Kinnear and Walker decided to collaborate to make things easier for themselves and make more money. Although the trains reached Benson between three and four a.m., the companies made no attempt to accommodate Tombstone-bound passengers until much later in the morning. They raised freight rates to five cents per pound and passenger fares to what was then an exorbitant charge of $10 for the 25-mile trip. They slowed down their coaches so that the trip took nearly twice as long as before. The former rivals then combined their companies into the Arizona Mail & Stage Company. For a short while Walker seemed to be the dominant partner. His large six-horse coaches carried all of the passengers, the mail, and the Wells Fargo box of cash and valuables. Kinnear’s coach followed along with express material and heavy freight.

Riding a stagecoach was not an especially enjoyable experience (Faulk, 1972, p 83-84). John Pleasant Gray rode a Kinnear and Walker Concord coach from Pantano to Tombstone in 1880 and stated:

"That day’s stage ride will always live in my memory–but not for its beauty spots. Jammed like sardines on the hard seats of an old time leather spring coach–a Concord–leaving Pantano, creeping much of the way, letting the horses walk, through miles of alkali dust that the wheels rolled up in thick clouds of which we receive the full benefit, we couldn’t then see much romance in the old stage method of traveling. . . . If it had not been for the long stretches when the horses had to walk, enabling most of us to get out and ‘foot it’ as a relaxation, it seems as if we could never have survived the trip."

New competition with the Kinnear-Walker monopoly on the line between Benson and Tombstone emerged when Robert Crouch, popularly known as “Sandy Bob,” formed an “opposition” line and on June 21, 1880 began carrying passengers between Benson and Tombstone (Peterson, 1968). On July 26, 1880 W. R. Ingram’s Tucson and Patagonia Stage Company also began daily service between Benson and Tombstone for $3 from Tombstone to Benson and three dollars and 50 cents from Benson to Tombstone (WAC, 1880). The company also offered service three times a week between Tombstone and Harshaw (mining camp about eight miles SE of Patagonia) for a fare of $6.00 each way.

Walker’s status as a senior partner within the Arizona Mail & Stage Company soon changed (Peterson, 1968). After Walker returned from a trip to San Francisco to purchase new stock, Kinnear demanded management changes. Kinnear had invested $3500 in the combined company but had not previously acted as an equal partner. Walker still owed Sam Hughes $2500 and had taken on additional debts when he purchased two carloads of new horses in San Francisco. Walker signed an agreement whereby he would receive a salary of $150 per month and Kinnear would take possession of the company’s coaches, stock, and other property in Benson, Tombstone and Harshaw. Kinnear would run the company and retain all profits until his investment had been paid off with interest. In November 1880 Walker became vice president and general superintendent for the combined line that Kinnear ran. However, in approximately 1881 Walker turned over to Kinnear his remaining interests in the Arizona Mail & Stage Company.

Kinnear reorganized some company operations and worked to eliminate a new arrival, Weston Ingram (Peterson, 1968). He agreed that his company would withdraw its competitive line on the Pantano to Harshaw route if Ingram’s Tucson and Patagonia Mail and stage Company halted its opposition runs between Benson and Tombstone. In October 1880 each company carried out the terms of the agreement and secured nearly a virtual monopoly on stage service within its own territory. Kinnear and Walker on November 20, 1880 obtained a contract for carrying mail to and from Bisbee. The Arizona Mail & Stage Company started running stages three times a week from Charleston to Bisbee.

Despite Kinnear’s best efforts the company faced increasing competition (Peterson, 1968). In December 1880 N. Smith’s Fast Freight and Passenger Line began offering stiff competition by charging only $2.50 for passage from Benson to Tombstone and at times charging only $1.00 or $2.00. When miners began to migrate to new mines in Mexico, Chester W. Pinkham established a Tombstone and Sonora Stage Line that provided weekly service along a route that traveled south from Tombstone and into Mexico.

Kinnear became tired of running a network of stage lines and on November 29, 1881 sold most of his line to William W. Hubbard and William D. Crow (Peterson, 1968). The $3800 sale included 20 horses equipped each with a harness, a coach called “Nelly Boyd,” a nine passenger coach, a “jerky” (light two-seat “with canvas top, capable of carrying 4-5 passengers), a spring wagon, and assorted curry combs and brushes. The new W. W. Hubbard & Company began running coaches three times a week to Bisbee and daily to Fort Huachuca. Kinnear continued making daily trips to Contention and Benson. In March 1882 Kinnear stages left Tombstone for Contention at 5 a.m. to connect with eastbound trains and departed from Tombstone at 12:20 PM to connect with westbound trains (TE, 1882a). The fares were (figures in parentheses are converted to 2014 dollars adjusted for inflation at the MW, 2015, site) $1.25 ($29.90) to Charleston, $1.50 ($35.80) to Contention, $3.50 ($83.60) to Hereford or Huachuca, and $6 ($143) to Bisbee.

Economic problems in the Tombstone area apparently made Kinnear think about leaving the stage business. On June 3, 1882 he advertised for sale in the Tombstone Epitaph (TE, 1882b) a 17-passenger Concord Coach, two 17-passenger Concord Mud Wagons, two 11-passenger Concord Mud Wagons, and one 9-passenger Concord Mud Wagon. He apparently was unable to sell these items and entered into an arrangement with Robert Crouch, popularly known as Sandy Bob, who was the Tombstone business manager for the Arizona Stage and Mail Company (Cobler, 1883, p. 147, 162 abs.)

Crouch was not discouraged by the Tombstone depression and in June 1882 added an extra two-horse mud wagon on the road to Contention City to meet competition from Newton Smith (Peterson, 1968). Smith subsequently went out of business in the last week of September 1882. Early in July 1882 Crouch and Kinnear purchased property in Charleston for a new and larger office and by August the Arizona Mail and Stage Company again was offering daily coaches to Charleston and Huachuca, offering service three times a week to Hereford and Bisbee, and providing transportation to the railroad at Contention City.

Tombstone’s fortunes continued to decline as the production of the mines fell drastically in 1883. Kinnear at the age of 46 decided to retire to his ranch in the Whetstone Mountains and at some point, probably in late 1883 or in 1884, entirely gave up his interests in the stage line to Robert Crouch. The latter continued to run the Arizona Mail and Stage Company. Stage travel declined as a result of the economic problems in Tombstone, and Crouch looked for ways to save money. In January 1883 he began refusing to transport the constable or deputy sheriff and prisoners from Bisbee to the county jail in Tombstone because the county paid with County script that was worth only approximately $.80 on the dollar, and recipients had to wait six months to receive even that discounted payment. In October 1883 he stopped service between Charleston and Huachuca because relatively few passengers rode the route, and it was losing money.

Tombstone’s economic problems continued in 1884 (Peterson, 1968). Meanwhile the Mexican town of Nacozari, located approximately 15 miles south of Bisbee, became a new center of silver mining activity. In the fall of 1884, R. C. Shaw, superintendent of the Luna Mine in Tombstone, and Michael Donovan, a blacksmith and Wilcox, together established the Arizona and Sonora Stage Company. The partners obtained contracts for carrying the U.S. mail and Wells Fargo’s express and in October 1884 began making weekly trips between Tombstone and Nacozari. Business for the line was good and it soon began using four-horse Concord coaches.

Tombstone’s economic problems continued in 1884 (Peterson, 1968). Meanwhile the Mexican town of Nacozari, located approximately 15 miles south of Bisbee, became a new center of silver mining activity. In the fall of 1884, R. C. Shaw, superintendent of the Luna Mine in Tombstone, and Michael Donovan, a blacksmith and Wilcox, together established the Arizona and Sonora Stage Company. The partners obtained contracts for carrying the U.S. mail and Wells Fargo’s express and in October 1884 began making weekly trips between Tombstone and Nacozari. Business for the line was good and it soon began using four-horse Concord coaches.

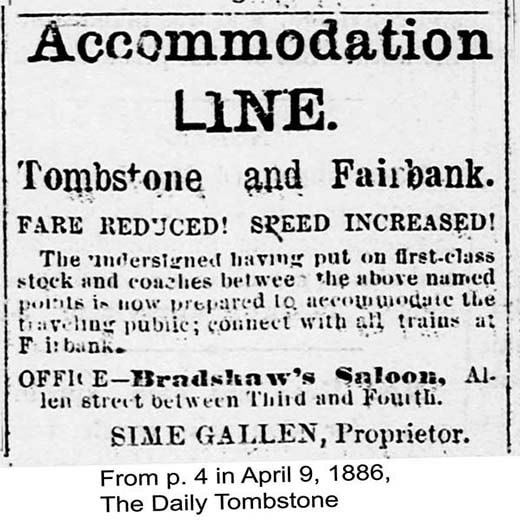

By the spring of 1886 it appeared that new pumping equipment was successfully lowering water level in the Tombstone mines (Peterson, 1968) and other entrepreneurs began to consider the stage business. Early in April two new stage lines appeared in Tombstone and offered competition to Sandy Bob. Sime Gallen, a former miner, advertised on April 1, 1886 (DT, 1886b) that his “Accommodation Line” was offering a reduced fare, increased speed, and first-class stock and coaches between Tombstone and Fairbank. On April 9, 1886 a second new competitors had an ad in the Daily Tombstone (DT, 1886c). Kimball C. Taft (under the name of Tom Taft), former driver for Sandy Bob (Cobler, 1883, p. 196, 211 abs.), advertised on page 3, “Third-Class Line. There will be another third-class or emigrant stage line start to-morrow morning between this city and Fairbank. Fare, 25 cents. Tom Taft, Proprietor. Harry Stevenson, Agt. At the Willows Saloon.” Similar ads for this $.25 service to Fairbank continued to appear in The Daily Tombstone through August 5, 1886 (DT, 1886l). Taft also was commonly called Tim and used the latter name for ads in 1898 onward about a stage company that he ran from Bisbee to Nacosari, a mining town in Mexico south of Douglas (WO, 1898).

Sandy Bob had worked hard for his monopoly on local stage service and was determined to keep it. The April 12, 1886 issue of The Daily Tombstone reprinted a report from the Nogales News that must have delighted potential passengers (DT, 1886d).

"Sandy Bob, the biggest man of his size, in his line in Cochise County, now has competition in the stage business from Fairbank to Tombstone, by a new line just started and fares have gone down. A small railroad war is likely to ensue. The new line cut the rate from the former price of $1.50 to $1.00 and Sandy Bob saw the cut and went one better, and now he hauls passengers without money and without price and if the war continues, he would doubtless throw in a chromo of Geronimo." [Chromo was a common abbreviation for chromolithograph, a type of color print.]

The Tombstone economy severely declined from May 1886 onward. A fire in the main shaft of the Grand Central Mine destroyed the massive water pumps there and the hoisting works, burning from May 26 until the morning of May 28 (DT, 1886f, 1886g). The owners of the mine had suffered a severe financial loss, impeding hopes of rebuilding the mine in the near future. Moreover, the price of silver began a decline (Peterson, 1968).

Stage business declined along with the Tombstone economy (Peterson, 1968). Sime Gallen left the stage business. The last ad for his stage company in available online Arizona newspapers was on October 4, 1886 (DT, 1886m). Gilbert S. Bradshaw, whose saloon had contained Gallen’s office, joined with Taft around 1 June 1886 to form a stage line that would carry passengers between Tombstone and Bisbee (DT, 1886h). They made an arrangement with Sandy Bob for him to discontinue his own service to Bisbee, thereby avoiding competition. The two partners moved their office into that of the Arizona Mail and Stage Company and began operations on 1 July (DT, 1886i, 1886j). In the absence of competition, the new line did well. The company continued in operation for several years. Bradshaw was still driving the stage to and from Bisbee as of January 18, 1889 (AWE, 1889), but he passed away January 16, 1890 from Bright’s Disease in San Francisco (TE, 1890a). Taft by October 23, 1898 owned the Bisbee and Nacosari Stage Line that offered weekly service from Bisbee to Nacosari, Mexico (WO, 1898).

Sandy Bob’s finances declined in the latter part of 1886, and he attempted to supplement his stage line income by other businesses. Tombstone residents considered Sandy Bob to be knowledgeable about eggs (DT, 1886a), and from April 29, 1886 until early August 1886 he sold at his stage office setting eggs of several varieties of chickens (DT, 1886e; DT, 1886k). In September, 1886 he mortgaged his ranch for $5000 to Charles W. Leach. To save money and keep his stage line intact he went back to driving the stage himself, and his son Charlie moved to town and rode shotgun (Peterson, 1968). On January 6, 1887 Sandy Bob finally sold his stage line to his former shotgun messenger, Robert Darragh and at the age of 56 retired on February 9, 1887 to his ranch in the Mule Mountains near Bisbee (DT, 1887). Sandy Bob was very popular in Cochise County and four localities in the Mule Mountains memorialize his memory, Sandy Bob Canyon, Sandy Bob Springs Windmill, Sandy Bob Tank, and Sandy Bob Windmill (GNIS, 2016).

Robert Darragh operated the Arizona Mail and Stage Line only slightly more than a year, finding that he had comparatively few passengers, with many of them traveling away from Tombstone as the economy declined (Peterson, 1968). He sold his interest in the company to Charles D. Gage, a local resident, and Martin D. Scribner, the Tombstone agent for Wells Fargo.

A temporary increase in the price of silver in 1890 and 1891 stimulated the Tombstone economy, and several new stage lines appeared and quickly disappeared (Peterson, 1968). Sime Gallen reentered the stage business and started weekly service on June 1, 1890 from Tombstone to the mining camp of Oso Negro in northern Sonora, near current day Cananea (TE, 1890b). He found in late October 1890 that driving a coach could be dangerous (AWE, 1890b). While he was stopped at the San Pedro custom house and was holding a team of bronco horses, the horses suddenly made a break and knocked him down and ran over him, with one wheel passing directly over his body. A mule tied to the back of the wagon began kicking him and broke several ribs, and Mrs. Gallen, his son, and a physician went there and transported him back to Tombstone for recuperation.

Finis E. Braly, a Tombstone rancher, and Arthur A. Kemp, a miner from Turquoise, began stage service to new silver mines at Turquoise, approximately 16 miles east of Tombstone in the Dragoon Mountains (Peterson, 1968). Alfred L. Brooks had in the meantime purchased the Bradshaw-Taft stage line to Bisbee and operated it for approximately a year until offering it for sale in August 1890.

Leonard A. Engle, a Bisbee miner, apparently purchased the equipment of the company and continued service between Tombstone and Bisbee. On September 22, 1890, Engle began service three times a week between Tombstone and Bisbee with a “fast two-horse rig.” He reduced the fare from $3.00 to $2.50 in November. In March 1892, with the price of silver again low and activity in the area slack, Engle quit the stage business. People traveling from Tombstone to Bisbee had to take a longer and more expensive route, going by stage to Fairbank and then by the Arizona and South eastern Railroad around the southern end of the Mule Mountains to Bisbee.

Gage and Scribner successfully operated the Arizona Mail and Stage Company for five years until the countrywide panic and depression of 1893 when silver prices dropped, and people left Tombstone in such numbers that sometimes two coaches were required at a time to take all the passengers to Fairbank (Peterson, 1968). Gage sold his interest, and Ralph A. Smith, for several years a teller with Bank of Tombstone, took this place as agent in the stage office. Floods in 1894 severely hampered stage service by washing out roads, flooding Fairbank, and destroying the corrals and sheds of the Arizona Mail and Stage Company. Financial problems prevented the company from doing any immediate rebuilding.

By the mid-1990s most of the smaller mining companies in the Tombstone area had gone out of business. Even the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company ceased operations by the end of 1896. Tombstone became nearly deserted. Toward the end of the century it began to appear as though the Grand Central Mines would again begin operation. On June 1, 1899 Charles B. Tarbell purchased the Arizona Mail and Stage Company from Scribner, receiving for $800 title to three six-horse coaches, one jerkey, and “nine horses (more or less).” Not much was left of the company that had once spanned the San Pedro Valley and reached as far as Tucson and Patagonia.

Stagecoach service continued in the first part of the 20th century, but with ever decreasing profits and fewer places that needed stage connections. A major blow to the stage industry in the San Pedro Valley area occurred in 1903 when the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad finished a nine-mile line between Fairbank and Tombstone. Many people did not mourn the end of the stagecoach era because newer forms of transportation were faster and more comfortable.

Sandy Bob had worked hard for his monopoly on local stage service and was determined to keep it. The April 12, 1886 issue of The Daily Tombstone reprinted a report from the Nogales News that must have delighted potential passengers (DT, 1886d).

"Sandy Bob, the biggest man of his size, in his line in Cochise County, now has competition in the stage business from Fairbank to Tombstone, by a new line just started and fares have gone down. A small railroad war is likely to ensue. The new line cut the rate from the former price of $1.50 to $1.00 and Sandy Bob saw the cut and went one better, and now he hauls passengers without money and without price and if the war continues, he would doubtless throw in a chromo of Geronimo." [Chromo was a common abbreviation for chromolithograph, a type of color print.]

The Tombstone economy severely declined from May 1886 onward. A fire in the main shaft of the Grand Central Mine destroyed the massive water pumps there and the hoisting works, burning from May 26 until the morning of May 28 (DT, 1886f, 1886g). The owners of the mine had suffered a severe financial loss, impeding hopes of rebuilding the mine in the near future. Moreover, the price of silver began a decline (Peterson, 1968).

Stage business declined along with the Tombstone economy (Peterson, 1968). Sime Gallen left the stage business. The last ad for his stage company in available online Arizona newspapers was on October 4, 1886 (DT, 1886m). Gilbert S. Bradshaw, whose saloon had contained Gallen’s office, joined with Taft around 1 June 1886 to form a stage line that would carry passengers between Tombstone and Bisbee (DT, 1886h). They made an arrangement with Sandy Bob for him to discontinue his own service to Bisbee, thereby avoiding competition. The two partners moved their office into that of the Arizona Mail and Stage Company and began operations on 1 July (DT, 1886i, 1886j). In the absence of competition, the new line did well. The company continued in operation for several years. Bradshaw was still driving the stage to and from Bisbee as of January 18, 1889 (AWE, 1889), but he passed away January 16, 1890 from Bright’s Disease in San Francisco (TE, 1890a). Taft by October 23, 1898 owned the Bisbee and Nacosari Stage Line that offered weekly service from Bisbee to Nacosari, Mexico (WO, 1898).

Sandy Bob’s finances declined in the latter part of 1886, and he attempted to supplement his stage line income by other businesses. Tombstone residents considered Sandy Bob to be knowledgeable about eggs (DT, 1886a), and from April 29, 1886 until early August 1886 he sold at his stage office setting eggs of several varieties of chickens (DT, 1886e; DT, 1886k). In September, 1886 he mortgaged his ranch for $5000 to Charles W. Leach. To save money and keep his stage line intact he went back to driving the stage himself, and his son Charlie moved to town and rode shotgun (Peterson, 1968). On January 6, 1887 Sandy Bob finally sold his stage line to his former shotgun messenger, Robert Darragh and at the age of 56 retired on February 9, 1887 to his ranch in the Mule Mountains near Bisbee (DT, 1887). Sandy Bob was very popular in Cochise County and four localities in the Mule Mountains memorialize his memory, Sandy Bob Canyon, Sandy Bob Springs Windmill, Sandy Bob Tank, and Sandy Bob Windmill (GNIS, 2016).

Robert Darragh operated the Arizona Mail and Stage Line only slightly more than a year, finding that he had comparatively few passengers, with many of them traveling away from Tombstone as the economy declined (Peterson, 1968). He sold his interest in the company to Charles D. Gage, a local resident, and Martin D. Scribner, the Tombstone agent for Wells Fargo.

A temporary increase in the price of silver in 1890 and 1891 stimulated the Tombstone economy, and several new stage lines appeared and quickly disappeared (Peterson, 1968). Sime Gallen reentered the stage business and started weekly service on June 1, 1890 from Tombstone to the mining camp of Oso Negro in northern Sonora, near current day Cananea (TE, 1890b). He found in late October 1890 that driving a coach could be dangerous (AWE, 1890b). While he was stopped at the San Pedro custom house and was holding a team of bronco horses, the horses suddenly made a break and knocked him down and ran over him, with one wheel passing directly over his body. A mule tied to the back of the wagon began kicking him and broke several ribs, and Mrs. Gallen, his son, and a physician went there and transported him back to Tombstone for recuperation.

Finis E. Braly, a Tombstone rancher, and Arthur A. Kemp, a miner from Turquoise, began stage service to new silver mines at Turquoise, approximately 16 miles east of Tombstone in the Dragoon Mountains (Peterson, 1968). Alfred L. Brooks had in the meantime purchased the Bradshaw-Taft stage line to Bisbee and operated it for approximately a year until offering it for sale in August 1890.

Leonard A. Engle, a Bisbee miner, apparently purchased the equipment of the company and continued service between Tombstone and Bisbee. On September 22, 1890, Engle began service three times a week between Tombstone and Bisbee with a “fast two-horse rig.” He reduced the fare from $3.00 to $2.50 in November. In March 1892, with the price of silver again low and activity in the area slack, Engle quit the stage business. People traveling from Tombstone to Bisbee had to take a longer and more expensive route, going by stage to Fairbank and then by the Arizona and South eastern Railroad around the southern end of the Mule Mountains to Bisbee.

Gage and Scribner successfully operated the Arizona Mail and Stage Company for five years until the countrywide panic and depression of 1893 when silver prices dropped, and people left Tombstone in such numbers that sometimes two coaches were required at a time to take all the passengers to Fairbank (Peterson, 1968). Gage sold his interest, and Ralph A. Smith, for several years a teller with Bank of Tombstone, took this place as agent in the stage office. Floods in 1894 severely hampered stage service by washing out roads, flooding Fairbank, and destroying the corrals and sheds of the Arizona Mail and Stage Company. Financial problems prevented the company from doing any immediate rebuilding.

By the mid-1990s most of the smaller mining companies in the Tombstone area had gone out of business. Even the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company ceased operations by the end of 1896. Tombstone became nearly deserted. Toward the end of the century it began to appear as though the Grand Central Mines would again begin operation. On June 1, 1899 Charles B. Tarbell purchased the Arizona Mail and Stage Company from Scribner, receiving for $800 title to three six-horse coaches, one jerkey, and “nine horses (more or less).” Not much was left of the company that had once spanned the San Pedro Valley and reached as far as Tucson and Patagonia.

Stagecoach service continued in the first part of the 20th century, but with ever decreasing profits and fewer places that needed stage connections. A major blow to the stage industry in the San Pedro Valley area occurred in 1903 when the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad finished a nine-mile line between Fairbank and Tombstone. Many people did not mourn the end of the stagecoach era because newer forms of transportation were faster and more comfortable.

Literature Cited

AC. 1871. J. F. Bennett & Co., Southern Overland Mail and Express Company [ad], p. 2. The Arizona Citizen. January 7, 1871. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 9, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1871-01-07/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1873. San Pedro Station [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday December 13, 1873. (PDF accessed June 19, 2015 http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1873-12-13/ed-1/seq-2/) .

AC. 1874a. San Pedro Station [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Saturday, March 7, 1874. (PDF accessed June 19, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-03-07/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1874b. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. May 9, 1874. (PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-05-09/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1874c. J. F. Bennett & Co. Southern Overland Mail and Ex. Co. [ad], p. 4. The Arizona Citizen. Saturday, June 27, 1874. (PDF accessed July 10, 1874 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-06-27/ed-1/seq-4/).

AC. 1875. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday, February 6, 1875. (PDF accessed July 20, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1875-02-06/ed-1/seq-1/).

AC. 1877. Land Patents. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Friday, November 30, 1877. (PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1877-11-30/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1879a. Tucson & Tombstone Stage Line [ad], p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. Friday March 14, 1879. (PDF accessed June 10, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-03-14/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879b. Notice. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Friday, August 15, 1879. (PDF accessed June 17, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-15/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879c. New Bridge on the San Pedro. The Arizona Citizen, p. 1. Friday, August 22, 1879. (PDF accessed July 18, 2014 at http://adnp.azlibrary.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sn82014896/id/984/rec/16).

AC. 1879d. Tucson and Tombstone Stage Line [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. JP2 accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-09-27/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879e. [Ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Saturday November 29, 1879. (PDF and JP2 accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-29/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879f. Tombstone Notes [From The Nugget, December 11]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday, December 13, 1879. (PDF accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-12-13/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1880. Local Matters, & Daily Mail to Tombstone, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. Friday, February 21, 1880. (PDF accessed August 10, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1880-02-21/ed-1/seq-3/).

ANSAC. 2006. Before the Arizona Navigable Stream Adjudication Commission in the Matter of the Navigability of the San Pedro River from the Mexican Border to the Confluence with the Gila River, Cochise, Pima, and Pinal Counties, Arizona. No. 03-004-NAV. Report, Findings and Determination Regarding the Navigability of the San Pedro River from the Mexican Border to the Confluence with the Gila River. Arizona Navigable Stream Adjudication Commission. 28 p. +23 p. attachments. (PDF accessed July 7, 2015 at http://www.ansac.az.gov/UserFiles/File/pdf/finalreports/San%20Pedro%20River.pdf).

AWE. 1889. Further Particulars, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. January 19, 1889. (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1889-01-19/ed-1/seq-3/).

AWE. 1890a. Stage to Benson, p. 4. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. January 11, 1890. (PDF accessed July 20, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-01-11/ed-1/seq-4/).

AWE. 1890b. The Mule Got Him, p 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. November 1, 1890. (PDF accessed July 1, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-11-01/ed-1/seq-3/).

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000b. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume Two: L-Z. Westernlore Press, Tucson. 246 p.

Barnes, W. C. 1988. Arizona Place Names. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 503 p.

BLM. 2015. Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. [Website at http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/search/default.aspx for searching public land records] (Accessed June 13, 2015, August 10, 2015).

Chapman [Publisher]. 1901. Portrait and Biographical Record of Arizona. Chapman Publishing Co., Chicago. 1034 p. (PDF accessed July 29, 2015 at https://archive.org/details/portraitbioarizo00chaprich).

Cobler. 1883. Tucson and Tombstone General and Business Directory for 1883 and 1884. . . . Cobler & Co., Tucson. 249 p. (PDF accessed August 27, 2014 at http://books.google.com/books?id=bmpNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA107&lpg=PA107&dq=church+1881+report+on+the+mines+and+mills+of+the+tombstone+mill+and+mining+company&source=bl&ots=Qg79S4frYk&sig=Pkh34BFC8IictOW2C2V-O70ZoiY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vXn-U76dBpHkoAS6xICgBA&ved=0CEYQ6AEwCDgK#v=onepage&q=church%201881%20report%20on%20the%20mines%20and%20mills%20of%20the%20tombstone%20mill%20and%20mining%20company&f=false).

DT. 1886a. Eggs, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. January 27, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-01-27/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886b. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. April 1, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-04/ed-1/seq-4/).

DT. 1886c. Third-Class Line, p. 3 [ad] Accommodation Line, p. 4 [ad]. The Daily Tombstone. April 9, 1886. (PDF & JP2 accessed June 30, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-09/ed-1/seq-3/, & http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-09/ed-1/seq-4/).

DT. 1886d. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. April 12, 1886. (PDF accessed June 30, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-12/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886e. Eggs for Sale [ad], p. 2. The Daily Tombstone. April 29, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-29/ed-1/seq-2/).

DT. 1886f. The Daily Tombstone, p. 2. May 27, 1886 (PDF accessed July 1, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-05-27/ed-1/seq-2/).

DT. 1886g. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. May 28, 1886. (PDF accessed July 1, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-05-28/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886h. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. June 4, 1886 (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-06-04/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886i. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. July 2, 1886 (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-07-02/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886j. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. July 3, 1886 (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-07-03/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886k. Eggs for Sale, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. August 2, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-08-02/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886l. The Daily Tombstone, p. 1. August 5, 1886. (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-08-05/ed-1/seq-1/).

DT. 1886m. The Daily Tombstone, p. 4. October 4, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-04/ed-1/seq-4/).

DT. 1887. Daily Tombstone Epitaph, p. 1. Wednesday, February 9, 1887. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn96060682/1887-02-09/ed-1/seq-1/).

Faulk, O. B. 1972. Tombstone Myth and Reality. Oxford University Press, New York. xi +242 p. Fault, O. B. 1972. Tombstone Myth and Reality. Oxford University Press, New York. xi +242 p.

GNIS. 2013. The Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). The Federal and national standard for geographic nomenclature. (Database at http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic).

Hinton, R. J. 1878. The Handbook to Arizona: It's Resources, History, Towns, Mines, Ruins, and Scenery. Payot, Upham & Co., San Francisco. American News Co., New York. 481 p. + 101 p. appendix. (PDF at http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=ewINAAAAIAAJ&output=acs_help).

Hodge, H. C. 1877. Arizona as it is; or, the Coming Country Compiled from Notes of Travel during the Years 1874, 1875, and 1876. Hurd and Houghton, Boston, Boston. 273 p. (PDF accessed October 3, 2013 at http://books.google.com/books?id=2X4UAAAAYAAJ&q=pedro#v=snippet&q=pedro&f=false).

Langley, H. G. 1875. The Pacific Coast Business Directory for 1876-78: Containing the Name and Post Office Address of Each Merchant, Manufacturer and Professional. . . . Henry G. Langley, Publisher, San Francisco. xcii ads, 812 p. directory + 32 p. separately paginated ads. (PDF accessed February 12, 2016 at https://archive.org/details/pacificcoastbusi187678lang).

McClintock, J. H. 1916a. Arizona, Prehistoric—Aboriginal—Pioneer—Modern. The Nation’s Youngest Commonwealth within a Land of Ancient Culture. Volume I. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., Chicago. x + p. 1-312. (PDF downloaded October 3, 2013 from http://books.google.com/books?id=gb8UAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Arizona,+Prehistoric,+Aboriginal,+Pioneer,+Modern&hl=en&sa=X&ei=WutNUtTZNcvoiAK0jICIAw&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Arizona%2C%20Prehistoric%2C%20Aboriginal%2C%20Pioneer%2C%20Modern&f=false).

MW. 2015. MeasuringWorth (Website calculator accessed June 24 2015 at (http://www.measuringworth.com/ppowerus/).

Parsons, G. W. 1996. A Tenderfoot in Tombstone. The Private Journal of George Whitewell Parsons: The Turbulent Years, 1880-82. Edited, Annotated, and with Introduction and Index by Lynn R. Bailey. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xvi + 253 p.

Peterson, T. H. 1968. The Tombstone Stagecoach Lines, 1878-1903: a Study in Frontier Transportation. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College. The University of Arizona. (PDF accessed June 13, 2015 at http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/handle/10150/552000).

PSP. 1907. History of New Mexico Its Resources and People. Illustrated. Vol. II. Pacific States Publishing Co., New York. p. 523-1047. (PDF accessed July 10, 2015 at https://archive.org/details/historyofnewmexi02paci).

SC. 1890. Transcript of Record. Supreme Court of the United States October Term, 1890. No. 313. The United States, Plaintiff in Error vs. John T. Chidester and Logan H. Roots. In Error to the Circuit Court of the United States for the Eastern District of Arkansas. Filed December 23, 1887. p. 1-186, 512-703 abs. (PDF consists of several independently paginated court cases, accessed June 16, 2015 at https://books.google.com/books?id=7HRBAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA2-PA72&lpg=RA2-PA72&dq=%22National+Mail+and+Transportation+Company%22&source=bl&ots=xeqdfSb7aw&sig=zxm97hgtzrMi-H0lyaTRXtsg8fk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCwQ6AEwA2oVChMIzJaF2PuUxgIVxp2ACh08egCs#v=onepage&q=%22National%20Mail%20and%20Transportation%20Company%22&f=false).

SFWG. 1867. Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line [ad], p. 2. Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, January 25, 1867. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 9, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022168/1868-01-25/ed-1/seq-2/).

SFWG. 1869. Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line [ad], p. 1. Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, June 29, 1869. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 9, 2015 at SFWG. 1867. Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line [ad], p. 2. Santa Fe Weekly Gazette. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 9, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022168/1869-06-26/ed-1/seq-1/).

TE. 1882a. Kinnear’s Stage Line, p. 3. Tombstone Daily Epitaph. Tuesday, March 7, 1882. (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016455/1882-03-07/ed-1/seq-3/).

TE. 1882b. For Sale ad]. Tombstone Epitaph, p. 2. Saturday, June 3, 1882. (PDF accessed June 28, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021939/1882-06-03/ed-1/seq-2/).

TE. 1890a. Tombstone Epitaph, p. 3. Saturday, January 18, 1890. (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1890-01-18/ed-1/seq-3/).

TE. 1890b. Tombstone Epitaph, p. 3. Saturday, May 31, 1890. (PDF accessed May 27, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1890-05-31/ed-1/seq-3/).

Thrapp, D. L. 1988a. Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography. Volume I, A-F. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln & The Arthur H. Clark Company, Spokane. xvi + 524 p.

US. 1881. Official Register of the United States Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service on the First of July, 1881. Volume II. The Post-Office Department and the Postal Service. Compiled and Printed under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior. Government Printing Office. Washington. iv + 892 p. (PDF accessed September 7, 2015 at https://books.google.com/books?id=CI0vAAAAMAAJ&pg=PR1&lpg=PR1&dq=1881+official+register+of+the+United+States+containing+a+list+of+officers+post-office+department&source=bl&ots=I-HxP14x6r&sig=J9axvULmda_qGvLMQou2Sz29-wI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAmoVChMI4tKE1qSxyAIV0ZuICh2XvQOl#v=onepage&q=Gannon&f=false)

USGS. 1915. Benson Quadrangle Arizona (Cochise 1/62 500). (Topographic). (PDF of map downloaded September 15, 2013 from http://store.usgs.gov/b2c_usgs/usgs/maplocator/(ctype=areaDetails&xcm=r3standardpitrex_prd&carea=%24ROOT&layout=6_1_61_48&uiarea=2)/.do).

WA. 1869. Southern Overland U.S. Mail and Express Line from Mesilla [ad], p. 4. The Weekly Arizonian, July 17, 1869. (PDF accessed July 9, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024829/1869-07-17/ed-1/seq-4/).

WAC. 1880. New Stage Lines, p. 3. Weekly Arizona Citizen. July 24, 1880. (PDF accessed Saturday February 24, 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016240/1880-07-24/ed-1/seq-3/).

WO. 1898. The Weekly Orb, p. 2. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94050504/1898-10-23/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1871. J. F. Bennett & Co., Southern Overland Mail and Express Company [ad], p. 2. The Arizona Citizen. January 7, 1871. (PDF & JP2 accessed July 9, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1871-01-07/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1873. San Pedro Station [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday December 13, 1873. (PDF accessed June 19, 2015 http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1873-12-13/ed-1/seq-2/) .

AC. 1874a. San Pedro Station [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Saturday, March 7, 1874. (PDF accessed June 19, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-03-07/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1874b. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. May 9, 1874. (PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-05-09/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1874c. J. F. Bennett & Co. Southern Overland Mail and Ex. Co. [ad], p. 4. The Arizona Citizen. Saturday, June 27, 1874. (PDF accessed July 10, 1874 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1874-06-27/ed-1/seq-4/).

AC. 1875. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday, February 6, 1875. (PDF accessed July 20, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1875-02-06/ed-1/seq-1/).

AC. 1877. Land Patents. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Friday, November 30, 1877. (PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at PDF accessed June 16, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1877-11-30/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1879a. Tucson & Tombstone Stage Line [ad], p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. Friday March 14, 1879. (PDF accessed June 10, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-03-14/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879b. Notice. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Friday, August 15, 1879. (PDF accessed June 17, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-15/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879c. New Bridge on the San Pedro. The Arizona Citizen, p. 1. Friday, August 22, 1879. (PDF accessed July 18, 2014 at http://adnp.azlibrary.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sn82014896/id/984/rec/16).

AC. 1879d. Tucson and Tombstone Stage Line [ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. JP2 accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-09-27/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879e. [Ad]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Saturday November 29, 1879. (PDF and JP2 accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-29/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879f. Tombstone Notes [From The Nugget, December 11]. The Arizona Citizen, p. 2. Saturday, December 13, 1879. (PDF accessed June 18, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-12-13/ed-1/seq-2/).

AC. 1880. Local Matters, & Daily Mail to Tombstone, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. Friday, February 21, 1880. (PDF accessed August 10, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1880-02-21/ed-1/seq-3/).

ANSAC. 2006. Before the Arizona Navigable Stream Adjudication Commission in the Matter of the Navigability of the San Pedro River from the Mexican Border to the Confluence with the Gila River, Cochise, Pima, and Pinal Counties, Arizona. No. 03-004-NAV. Report, Findings and Determination Regarding the Navigability of the San Pedro River from the Mexican Border to the Confluence with the Gila River. Arizona Navigable Stream Adjudication Commission. 28 p. +23 p. attachments. (PDF accessed July 7, 2015 at http://www.ansac.az.gov/UserFiles/File/pdf/finalreports/San%20Pedro%20River.pdf).

AWE. 1889. Further Particulars, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. January 19, 1889. (PDF accessed July 3, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1889-01-19/ed-1/seq-3/).

AWE. 1890a. Stage to Benson, p. 4. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. January 11, 1890. (PDF accessed July 20, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-01-11/ed-1/seq-4/).

AWE. 1890b. The Mule Got Him, p 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. November 1, 1890. (PDF accessed July 1, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-11-01/ed-1/seq-3/).

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000b. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume Two: L-Z. Westernlore Press, Tucson. 246 p.

Barnes, W. C. 1988. Arizona Place Names. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 503 p.

BLM. 2015. Bureau of Land Management. General Land Office Records. [Website at http://www.glorecords.blm.gov/search/default.aspx for searching public land records] (Accessed June 13, 2015, August 10, 2015).

Chapman [Publisher]. 1901. Portrait and Biographical Record of Arizona. Chapman Publishing Co., Chicago. 1034 p. (PDF accessed July 29, 2015 at https://archive.org/details/portraitbioarizo00chaprich).

Cobler. 1883. Tucson and Tombstone General and Business Directory for 1883 and 1884. . . . Cobler & Co., Tucson. 249 p. (PDF accessed August 27, 2014 at http://books.google.com/books?id=bmpNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA107&lpg=PA107&dq=church+1881+report+on+the+mines+and+mills+of+the+tombstone+mill+and+mining+company&source=bl&ots=Qg79S4frYk&sig=Pkh34BFC8IictOW2C2V-O70ZoiY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vXn-U76dBpHkoAS6xICgBA&ved=0CEYQ6AEwCDgK#v=onepage&q=church%201881%20report%20on%20the%20mines%20and%20mills%20of%20the%20tombstone%20mill%20and%20mining%20company&f=false).

DT. 1886a. Eggs, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. January 27, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-01-27/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886b. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. April 1, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-04/ed-1/seq-4/).

DT. 1886c. Third-Class Line, p. 3 [ad] Accommodation Line, p. 4 [ad]. The Daily Tombstone. April 9, 1886. (PDF & JP2 accessed June 30, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-09/ed-1/seq-3/, & http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-09/ed-1/seq-4/).

DT. 1886d. The Daily Tombstone, p. 3. April 12, 1886. (PDF accessed June 30, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-12/ed-1/seq-3/).

DT. 1886e. Eggs for Sale [ad], p. 2. The Daily Tombstone. April 29, 1886. (PDF accessed July 4, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-04-29/ed-1/seq-2/).