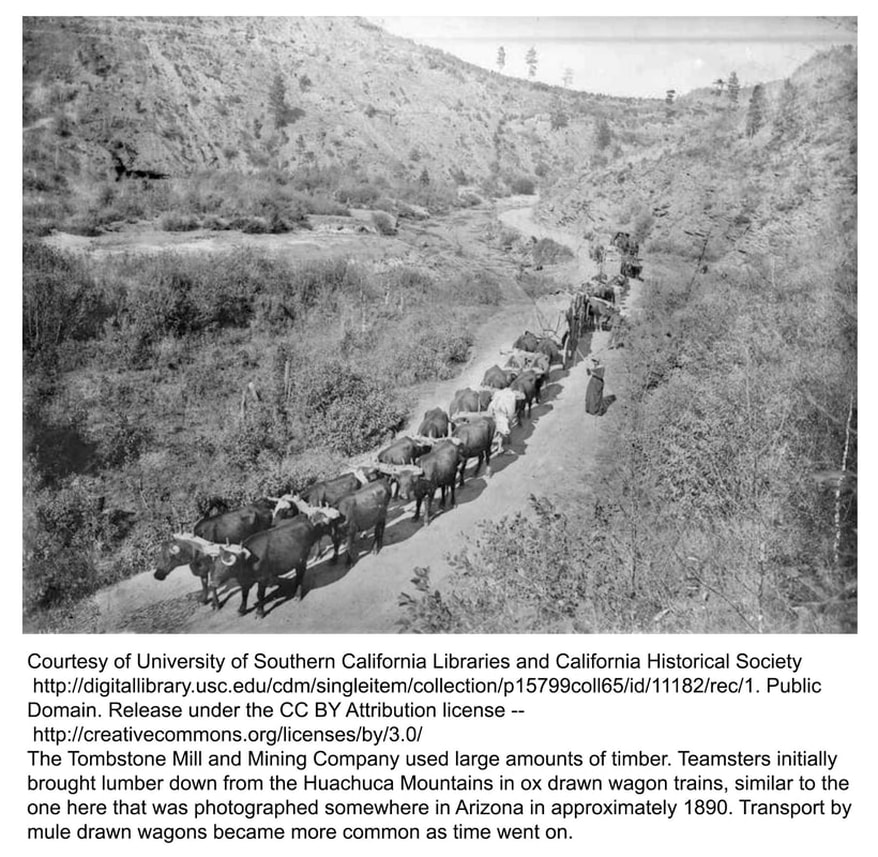

Ox drawn cart similar to the ones used to transport wood from the Huachuca Mountains.

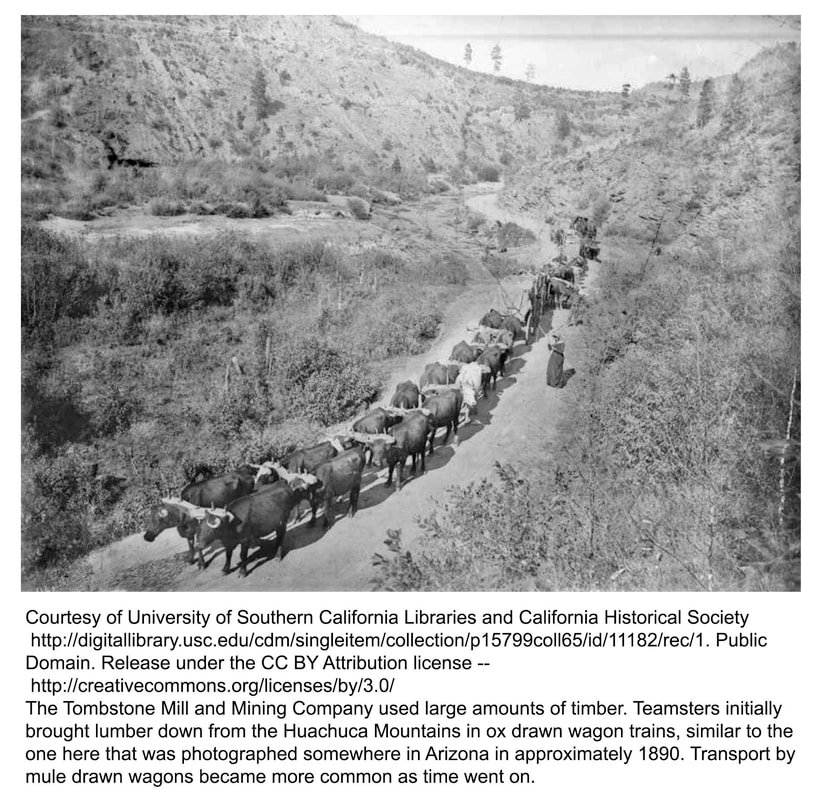

Ox drawn cart similar to the ones used to transport wood from the Huachuca Mountains.

Gerald R Noonan PhD

Text © February 2019

(Excerpt from book manuscript about the human and environmental history of the San Pedro River Valley and adjacent areas from the Gadsden Purchase to statehood.)

The discovery of valuable ores in the Tombstone and Bisbee areas and elsewhere sparked a mining boom that attracted people to such places and to the San Pedro River Valley. Wood was urgently needed for the development of mines, mills, businesses, and homes. The Tombstone mines and mills were most active during the Tombstone Bonanza years from June 1879 through December 1886 (Bahre and Hutchinson, 1985, p. 181). The Copper Queen Company and other mines in the Bisbee area continue to need large amounts of construction timber after the Tombstone mines declined.

The largest stands of construction grade lumber near Tombstone and Bisbee were coniferous forests of approximately 20,000 acres in the Huachuca Mountains and 50,000 acres in the Chiricahua Mountains (Kellogg, 1902; TDE, 1889). These forests occurred at elevations of 7000 feet or above because only such higher reaches had enough precipitation for the trees. The Pinus ponderosa species complex was the predominant type of tree at these higher elevations and furnished almost all the lumber first used for construction in the Tombstone area. While this type of tree was the principal source of local lumber, its quality was poor, knotty and often with rotten streaks and many blind knots. In the early days of the Tombstone Bonanza, this lumber was in great demand because it was cheaper than wood brought from outside of Arizona by wagon trains.

The army apparently was the first organization to harvest construction timber from the Huachuca Mountains (Spring and Gustafson, 1966, p. 58, 111). The short-lived Camp Wallen on the Babocomari River sent soldiers in 1866 to the vicinity of present-day Fort Huachuca to cut timber for rafters and lintels for buildings being constructed at the camp. In 1867 eight soldiers were still harvesting timber at a temporary camp in the mountains.

In the spring of 1879, Captain Whitside, first commander of Fort Huachuca, had soldiers begin running a sawmill near the mouth of Huachuca Canyon to obtain lumber for constructing buildings on the post (Lage, 1949; Smith, 1981, p. 26). Soldiers had to climb considerably higher into the Huachuca Mountains to cut down pine trees and then skin the trunks and snake the large logs down the mountainside. They used their own muscle power and that of mules to get the timber to the sawmill. Men who committed misdemeanors were condemned to hard labor at the sawmill camp. Those who volunteered or were detailed to this work received extra pay of $0.20 per day for enlisted soldiers and $0.35 for sergeants, corporals, and enlisted men whose expertise or training qualified them to work as masons, carpenters, or blacksmiths.

In 1867 a Tucson Catholic Church that needed lumber for a schoolhouse roof cut it from the Huachuca Mountains because it was easier to reach the pine woods there than those in the Santa Rita Mountains (Farish, 1916b, p. 298-299, 314-315 abs.). The Huachuca Mountains were conveniently close to Tombstone and its mills, and people knew about their timber (O’Leary, 1877).

Four commercial sawmills in the Huachuca Mountains initially supplied construction grade lumber (AC, 1879c,h; ADS, 1880c,d; AQI, 1880, p 4; Bahre, 1991 p. 168-169; Bailey, 2004, p. 66; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 54; Garner vs. Gird, 1885, p. 59, 150-15 2, 160; Matheny, 1975, p. 5- 8; MSP, 1881; Spencer, 1966; Underhill, 1979, p. 64). Richard Gird and his associates arranged for 24,000 pounds of sawmill machinery to be transported by ship around Cape San Lucas, up the Gulf of California and then via the Colorado River to Yuma where it arrived on November 16, 1878 (AS, 1878; Fulton, 1966; LAH, 1878). The mining partners chartered a wagon train outfit from Meyers & Bowley at extra rates to speedily deliver the machinery to the Huachuca Mountains. The exact location of the Gird Mill is unknown. The Gird sawmill was described in July 1880 as located on the western side of the Huachuca Mountains “high up on the northern side of McCloskey cañon.” The name McCloskey was a misspelling of McCluskey and referred to one of the partners who owned the mill and did not become an accepted designation of a place in the mountains. Bailey and Chaput (2000a, p. 54) regarded the mill as in Sawmill Canyon within the Huachuca Mountains, Matheny, (1975, p. 35) placed it in Ramsey Canyon, and Wilson (1995, p. 208) believed it was in Carr Canyon. People who went into Carr Canyon to see part of the Huachuca Water Company’s pipeline in 1882 could see the Gird Mill in the distance (TWE, 1882). The June 10, 1880 issue of the Weekly Nugget, as quoted by Bahre (1991, p. 168), said that the mill originally began operations at Saw Mill Canyon and after harvesting the timber in that area was moved to the top of the mountains at 8000 feet. The region of the canyon is on the western side of the mountains west of Ramsey Peak (1958 and 2018 Miller Peak topographic maps).

Gird had persuaded his brother William to run the sawmill. William partnered with John McCluskey to run it. The two partners owned the mill and initially had an arrangement with the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company to supply its lumber needs. Lumber not needed by the mining company was shipped to the mining company which then distributed it to other parties. The arrangement with the mining company specified that the partners would furnish lumber at $50 per thousand feet and that the partners could sell excess wood at whatever price they could obtain. The money from the sale of all lumber went to the mining company until it was paid for the cost of the mill. The mining company received a bargain because the price to other parties in May 1879 was $100 per 1000 feet (AC, 1879k).

William Gird and McCluskey laid the foundations and then erected the mill which began shipping lumber to Millville and Tombstone on January 14, 1879. In March 1879, the partners agreed to Thomas Bidwell’s proposal that he and W. H. Harwood sell lumber not needed by the mining company for a commission of 5% of the proceeds. Bidwell stopped selling timber in June 1879 when he went East. Harwood continued selling it until January 1880.

The sawmill’s need for logs resulted in an August 1879 advertisement seeking lumbermen and teamsters for logging in the Huachuca Mountains and hauling logs to the sawmill (AC, 1879j). The Tombstone Mill and Mining Company sought a total of 1 million feet of logs and would receive bids until August 20, 1879.

Ownership of the mill changed in 1880. McCluskey transferred his interest to William Gird in February, and James Carr bought the mill in April. Carr specialized in lumber for mining purposes and provided it not only for the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company and a yard in Tombstone but also filled contracts for the Boston and Arizona Mill and The Tombstone and Charleston Ice Company (Matheny, 1975, p. 36; Rose, 2012, p. 30).

By April 1880, the sawmill had produced approximately three million feet of lumber which was sold primarily in the Tombstone District. Six men worked the mill, 25 more men cut timber and served as teamsters, and 12 yoke of oxen and 35 span of mules pulled wagons and sleds with timber. The lumber was primarily used for mine timbers and for constructing mining and milling facilities, and boarding houses. The remaining accessible supply of uncut timber was estimated

at 3,500,000 feet. Demand for lumber was so high that a night shift began running the mill in the spring of 1882 to increase its output.

Ad for shakes, shingles & mining timber

Ad for shakes, shingles & mining timber

Early in 1879 John Campbell and other Mormons set up a sawmill in the Huachuca Mountains in Miller’s Canyon, sometimes called Mormon Canyon because of the Mormon sawmill (ADS, 1880c; Bailey, 2004, p. 66; McClintock, 1921, p. 236, 301 abs.). By October 1879, the sawmill was producing 3000 to 5000 feet of lumber a day (ADS, 1879c). Most lumber went to the Contention Mill, with the rest going to Turner’s lumber yard in Tucson. In November 1879, the Mormons had a disagreement among themselves and decided to sell the mill. John N. Turner acquired the mill in late 1879 or early 1880 and moved the mill, which was designed to be portable, to Ramsey Canyon (AC, 1879g; AQI, 1880, p. 4; AS, 1879b; Bahre, 1991, p. 168-169; Bailey, 2004, p. 25-31). Turner in March 1880 built a good wagon road up Ramsey Canyon along an old burro trail (AC, 1880). In April of that year he refurbished the former Mormon sawmill and soon had it running at full capacity (ADS, 1880d; AQI, 1880, p. 4; Bailey, 2004, p. 66; Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 161).

Turner had a lumber yard in Tombstone that sold wood from the Huachuca Mountains. The estimated uncut timber in the canyon as of July 1880 was four million feet, 400,000 of which would be processed before the mill was moved a mile or two higher up the canyon. Turner found an eager market in Tombstone for his lumber at an average rate of $55 per thousand feet. In June 1880 Turner sold his lumber yard to Philip Morse, who had W. H. Harwood, former mayor of Tombstone, run it for him (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 161).

The nearest settlement to the first mill site in Ramsey Canyon was two miles below the sawmill and was named Turnersville in April 1880 after John Turner. The small town served as a local social hub (ADS, 1880d). For example, a dance at the home of Richards and Hill on June 15, 1880 attracted 20 ladies and approximately 50 men. Several participants came from Tombstone. The hosts provided the music for the dance. Brown’s hotel supplied excellent accommodations for travelers and visitors. Enough funds had been pledged to build a schoolhouse, and a teacher had been hired. Residents in the area were looking forward to a pleasant time in the town on July 4 and expected 200 people to take part. Turner was scheduled to give a talk after which there would be dancing.

Francis Tanner and William L. Hayes established a sawmill on the eastern side of the Huachuca Mountains in the fall of 1879, with its output supplying the Patagonia District (AC, 1880; ADS, 1879a; AQI, 1880, p. 4; Bahre, 1991, p. 168; Bailey, 2004, p. 66; Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 149). By the latter part of September 1879, the mill was furnishing excellent quality lumber at a cost of $65 per thousand feet, with the output being bought the moment it was delivered in Harshaw for use in buildings that were being constructed. The mill continued in 1880 to find a ready market for its output and employed more than 30 men, but a boiler explosion destroyed it. A new mill soon was producing 7000 to 8000 feet of lumber a day and by July 1880 had cut more than 400,000 feet of lumber.

A religious commune in Sunnyside Canyon on the southwestern side of the Huachuca Mountains set up a sawmill late in 1894 to augment revenues from a mine it ran (LAT, 1896; Peterson, 1999; Wilson, 1995, p. 208). The mill’s principal market was Washington Camp, a mine in the Patagonia Mountains, and the mill ran for approximately 25 years until it lost that market.

The army was the first organization that logged within the Chiricahua Mountains (Bennett, 1865; Meketa & Meketa, 1980, p. 19-20; SFWG, 1864; Wilson, 1995, p. 209). On July 10, 1864 Captain T. T. Tidball left Fort Bowie on a scout for Indians with 16 California and New Mexico volunteers. His report mentioned the abundance of pine timber in the upper part of Pine Canyon and that much of it could be reached by wagon “without difficulty.” Tidball noted the plentiful timber at other locations and suggested that all the lumber needed for building Fort Bowie could be obtained from the Chiricahua Mountains. Lieutenant Colonel Bennett, commander of Fort Bowie, in early 1865 sent 17 New Mexico Volunteers to the Chiricahua Mountains to establish a lumber camp with sawpits and to harvest timber. In July 1865, 20 soldiers and a sergeant from the New Mexico Volunteers went to Ajo del Carrizo to obtain lumber for construction. Another detail of soldiers left the fort on August 31, 1865 to relieve the first group. During October 1865, a group of California Volunteers went to protect the loggers from Apaches thought to be near the lumber camp.

Citizens also knew about the abundant timber in the Chiricahua Mountains. The Arizona Citizen on October 26, 1878 published an article about wood in southern Arizona that mentioned the abundant timber in the Chiricahua Mountains (AC, 1878). The first commercial sawmill in the Chiricahua Mountains began operations in 1879. Philip E. Morse convinced Jacob Grundike, a prominent banker and cattleman in California, to accompany him to southeastern Arizona and invest in a sawmill. The two men arrived in Tucson from San Diego in early April 1879 and searched for a suitable place for erecting a large sawmill that would produce lumber at prices below that for lumber imported from California (AC, 1879a,b,d,f,i; ADS, 1879c,d; ADS, 1880a,b; Bahre, 1991, p. 170; Matheny, 1975 p. 37-38; Patt, 2013; USDA, 2003, p. 16; WAC, 1880a,b). They found such a site on the western slopes of the Chiricahua Mountains in Turkey Creek Canyon 22 miles south of Fort Bowie. (The canyon was sometimes termed Morse Canyon or Morse Creek [Barnes, 1988, p. 290, 458-459].)

Morse began superintending the cutting of logs and their transportation to the future mill site. Grundike departed Tucson on April 17 for San Francisco to buy a sawmill. He ordered from H. R. Rice of San Francisco a large sawmill with a 12x12 engine powered by a boiler capable of producing 30-40 hp. The 20,000 pounds of machinery for the mill was shipped by railroad on May 20, 1879 to the end of the Southern Pacific Railroad where it was loaded onto a Barnett & Block wagon train that subsequently trundled through Tucson on June 14, 1879 on the way to the Chiricahuas.

The sawmill began running on July 18, 1879, and a shingle making machine was shipped from A. D. Otis & Company on July 24, 1879. By July 1879 Morse & Co. was advertising that through a lumber yard in Tucson it provided “All Kinds of Lumber,” along with “Matched Flooring” and shingles. The Morse sawmill in 1880 produced the first tongue and grooved surfaced flooring and ceiling materials made in Pima County. The demand for lumber was greater than the capacity of the mill. During the first nine months of operation the mill shipped more than 1 million feet of lumber, mostly to Tombstone and adjacent mills. In May 1880 it was cutting 50,000 feet of lumber per week. By July 10, 1880, the company was advertising that its agent in Tombstone had on hand 200,000 feet of lumber suitable for mining, building materials, seasoned flooring, rustic shingles, etc. The sawmill shut down in early November 1882 (AWC, 1882). Morse returned to San Diego and by September 1887 was worth $250,000 in lumber and real estate (TE, 1887).

William Downing erected a substantial sawmill in December 1879 in Pinery Canyon in the Chiricahua Mountains 20 miles south of Fort Bowie (ADS, 1880a,e; AS, 1879a,b; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 100-101; Patt, 2013). The mill began working in January 1880, with many orders already on hand. It supplied lumber to Tombstone for buildings and mines and shipped considerable wood to Tucson (ADS, 1891; Matheny, 1975 p. 37-38). The Cochise County delinquent tax rolls for the year ending 1887 showed that Downing had delinquent taxes of $37.41 on property valued at $1125 (TWE, 1888). The property included a ranch in Pinery Canyon, improvements to the ranch, a sawmill, a house in Dos Cabezas, and miscellaneous items such as harnesses and tools.

In the spring of 1888 Downing moved the sawmill higher up within the Chiricahua Mountains to an area where he believed there was enough timber to run his mill for several years (ADS, 1888). The sawmill temporarily closed in the summer of 1889 when the Copper Queen Company briefly reduced its operations and was using very little lumber (ASB, 1889). A fire of unknown origin destroyed the sawmill and 30,000 feet of lumber in mid July 1891 (ADS, 1891; TWE, 1891a). Downing immediately rebuilt the mill.

In approximately 1895 Downing sold his mill to the Riggs Bros. & Co. (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, 82-83; Patt, 2013; Potter, 1902; Wilson, 1995, p. 211). The many members of the Riggs family were developing a large cattle operation along the eastern flanks of the Chiricahua Mountains and collectively in time owned approximately 100,000 acres of patented land, controlled about 25,000 acres under forest reserve permits, and held about 50,000 acres by leases. The family operated the former Downing mill in Pine Canyon and later moved it higher within the canyon and then to Barfoot Park, approximately 7.5 miles west of Portal (1994 Chiricahua Peak topographic map 31109-E1-TM-100). The mill eventually logged most of the Barfoot region (Russell, 1982, p. 69-94). Brannick Riggs, Jr. estimated in 1902 that the forest near the mill would supply 4 million board feet of lumber. In 1903 he contracted to supply the Detroit Copper Company at Morenci with 600,000 feet of lumber that would be hauled 15 miles to the Rodella station of the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and then shipped to the company by rail (BDR, 1903; CS, 1903).

Edward F. Sweeney of the Duluth & Chiricahua Development Company bought the Riggs mill in May 1904 for $8000 along with related items such as adjacent track, cars, horses, a logging truck and wagon, and the right to harvest and sell timber from the Chiricahua Forest Reserve under a contract with the federal government (Patt, 2013). The new sawmill company was alternatively called the Sweeney Lumber Company and the Chiricahua Lumber Mills Company. The sawmill supplied lumber to the nearby developing mining town of Paradise and to the Paradise Mining District in the Chiricahua Mountains (BDR, 1904; BDR, 19005; BDR, 1906a,b; GNIS, 2018; TWE, 1906).

In June 1906, the company sold out to Boyer and Sanders with the sale including the mill machinery and all buildings on the ground, all the cut and cured lumber, all wood left over from earlier timber logging, and the right to all standing timber near the mill and in Rustlers’ Park. The new firm announced plans to fill a contract with a mine at Pearce for 2,000,000 feet of mining timber produced at the rate of 50,000 to 60,000 feet per month and to supply mining timber and other lumber to anyone who wished to buy it. In the spring of 1907, the sawmill was removed from Barfoot Park (Pilsbry and Ferriss, 1910).

The sawmill of Daniel Ross harvested thousands of feet of lumber from the Chiricahua Mountains during the 1880s and early 1890s (ASB, 1889; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 92; AWE, 1890; Douglas, 1906, p. 27; Patt, 2013; DT, 1886d; TDE, 1886a,b; TDP, 1890; TWE, 1891c). In 1883 Daniel D. Ross and Jacob Scheerer partnered to buy a sawmill in either John Long or Mormon Canyon. Scheerer sold his share of the facility to Ross in 1886, and the latter subsequently moved the mill into Rock Canyon. After the mill gained the Copper Queen Company as its major customer, it sent most of its output to Bisbee for the company. Most of the timbers wanted by the Copper Queen were 12 x 12 and 10 x 10 in thickness. The mill in April 1890 was cutting 15,000 feet of timber per day and hauling it to Bisbee. The Copper Queen Company was taking all the native lumber it could obtain and importing a significant amount from Oregon. However, the company then preferred local timber because managers believed it was tougher and would stand more severe strains.

In April and May of 1886 and in July 1890 the mill advertised for heavy teams for hauling lumber from it to Bisbee. In the summer of 1889, the sawmill temporarily closed because the Copper Queen Company had momentarily reduced its operations and was using little lumber. The Ross Mill in November 1891 was running full time and producing about 20,000 feet of lumber per day, all of which went to Bisbee. The mill shut down in March 1894 because Ross concluded that it was impossible to make a profit because of the expenses of defending against a federal lawsuit.

During at least the latter part of 1886 Holmes & Thompson sold lumber from their mill at the head of Morse’s Canyon in the Chiricahua Mountains (DT, 1886a,b,e).

The Copper Queen Company and other Bisbee mines first harvested timber from the Mule Mountains (AWC, 1893; Douglas, 1906, p. 27; Douglas, 1910, p. 429, 496 abs.; Schwantes, 2000, p. 90; TWE, 1891b; USDA, 2003, p. 16). However, these mountains were relatively low in elevation compared to the other mountains in southeastern Arizona and supplied only limited amounts of what Douglas termed “stunted wood.”

By the end of the 1880s the Mule Mountains’ supply of lumber suitable for construction was mostly exhausted and could no longer meet the needs of the Bisbee mines. The Copper Queen switched in the middle 1880s to obtaining construction timbers from the Ross mill. Because of the legal expenses incurred in defending itself against a federal civil suit resulting from the purchase of Ross lumber, the Copper Queen Company in 1892 began looking elsewhere for suitable lumber. It found that it could obtain Oregon pine delivered to Benson or Fairbank for $19-$20 per thousand feet versus $32 per thousand feet for lumber from the Chiricahua Mountains delivered in Bisbee. The Southern Pacific imported the timber through San Pedro, California and transported it to Benson.

For several years, the inadequate supply of cut lumber was a limiting factor on the erection of buildings and the development of mines in southeastern Arizona. There was a great scarcity of lumber in Tucson in the latter part of 1879 (PH, 1879). Thirty-four buildings, mostly business houses, were under contract in Tombstone, but builders were waiting for the arrival of lumber so that they could construct the buildings. The Arizona Citizen noted on November 8, 1879 (AC, 1879e) that a dispute among the workers at a sawmill resulted in a shortage of lumber that hampered operations of the Contention Mill. The demand for lumber during 1880 was so great that sawmills could not meet the demands of Tombstone based mining companies (WAC, 1880c).

Turner had a lumber yard in Tombstone that sold wood from the Huachuca Mountains. The estimated uncut timber in the canyon as of July 1880 was four million feet, 400,000 of which would be processed before the mill was moved a mile or two higher up the canyon. Turner found an eager market in Tombstone for his lumber at an average rate of $55 per thousand feet. In June 1880 Turner sold his lumber yard to Philip Morse, who had W. H. Harwood, former mayor of Tombstone, run it for him (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 161).

The nearest settlement to the first mill site in Ramsey Canyon was two miles below the sawmill and was named Turnersville in April 1880 after John Turner. The small town served as a local social hub (ADS, 1880d). For example, a dance at the home of Richards and Hill on June 15, 1880 attracted 20 ladies and approximately 50 men. Several participants came from Tombstone. The hosts provided the music for the dance. Brown’s hotel supplied excellent accommodations for travelers and visitors. Enough funds had been pledged to build a schoolhouse, and a teacher had been hired. Residents in the area were looking forward to a pleasant time in the town on July 4 and expected 200 people to take part. Turner was scheduled to give a talk after which there would be dancing.

Francis Tanner and William L. Hayes established a sawmill on the eastern side of the Huachuca Mountains in the fall of 1879, with its output supplying the Patagonia District (AC, 1880; ADS, 1879a; AQI, 1880, p. 4; Bahre, 1991, p. 168; Bailey, 2004, p. 66; Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, p. 149). By the latter part of September 1879, the mill was furnishing excellent quality lumber at a cost of $65 per thousand feet, with the output being bought the moment it was delivered in Harshaw for use in buildings that were being constructed. The mill continued in 1880 to find a ready market for its output and employed more than 30 men, but a boiler explosion destroyed it. A new mill soon was producing 7000 to 8000 feet of lumber a day and by July 1880 had cut more than 400,000 feet of lumber.

A religious commune in Sunnyside Canyon on the southwestern side of the Huachuca Mountains set up a sawmill late in 1894 to augment revenues from a mine it ran (LAT, 1896; Peterson, 1999; Wilson, 1995, p. 208). The mill’s principal market was Washington Camp, a mine in the Patagonia Mountains, and the mill ran for approximately 25 years until it lost that market.

The army was the first organization that logged within the Chiricahua Mountains (Bennett, 1865; Meketa & Meketa, 1980, p. 19-20; SFWG, 1864; Wilson, 1995, p. 209). On July 10, 1864 Captain T. T. Tidball left Fort Bowie on a scout for Indians with 16 California and New Mexico volunteers. His report mentioned the abundance of pine timber in the upper part of Pine Canyon and that much of it could be reached by wagon “without difficulty.” Tidball noted the plentiful timber at other locations and suggested that all the lumber needed for building Fort Bowie could be obtained from the Chiricahua Mountains. Lieutenant Colonel Bennett, commander of Fort Bowie, in early 1865 sent 17 New Mexico Volunteers to the Chiricahua Mountains to establish a lumber camp with sawpits and to harvest timber. In July 1865, 20 soldiers and a sergeant from the New Mexico Volunteers went to Ajo del Carrizo to obtain lumber for construction. Another detail of soldiers left the fort on August 31, 1865 to relieve the first group. During October 1865, a group of California Volunteers went to protect the loggers from Apaches thought to be near the lumber camp.

Citizens also knew about the abundant timber in the Chiricahua Mountains. The Arizona Citizen on October 26, 1878 published an article about wood in southern Arizona that mentioned the abundant timber in the Chiricahua Mountains (AC, 1878). The first commercial sawmill in the Chiricahua Mountains began operations in 1879. Philip E. Morse convinced Jacob Grundike, a prominent banker and cattleman in California, to accompany him to southeastern Arizona and invest in a sawmill. The two men arrived in Tucson from San Diego in early April 1879 and searched for a suitable place for erecting a large sawmill that would produce lumber at prices below that for lumber imported from California (AC, 1879a,b,d,f,i; ADS, 1879c,d; ADS, 1880a,b; Bahre, 1991, p. 170; Matheny, 1975 p. 37-38; Patt, 2013; USDA, 2003, p. 16; WAC, 1880a,b). They found such a site on the western slopes of the Chiricahua Mountains in Turkey Creek Canyon 22 miles south of Fort Bowie. (The canyon was sometimes termed Morse Canyon or Morse Creek [Barnes, 1988, p. 290, 458-459].)

Morse began superintending the cutting of logs and their transportation to the future mill site. Grundike departed Tucson on April 17 for San Francisco to buy a sawmill. He ordered from H. R. Rice of San Francisco a large sawmill with a 12x12 engine powered by a boiler capable of producing 30-40 hp. The 20,000 pounds of machinery for the mill was shipped by railroad on May 20, 1879 to the end of the Southern Pacific Railroad where it was loaded onto a Barnett & Block wagon train that subsequently trundled through Tucson on June 14, 1879 on the way to the Chiricahuas.

The sawmill began running on July 18, 1879, and a shingle making machine was shipped from A. D. Otis & Company on July 24, 1879. By July 1879 Morse & Co. was advertising that through a lumber yard in Tucson it provided “All Kinds of Lumber,” along with “Matched Flooring” and shingles. The Morse sawmill in 1880 produced the first tongue and grooved surfaced flooring and ceiling materials made in Pima County. The demand for lumber was greater than the capacity of the mill. During the first nine months of operation the mill shipped more than 1 million feet of lumber, mostly to Tombstone and adjacent mills. In May 1880 it was cutting 50,000 feet of lumber per week. By July 10, 1880, the company was advertising that its agent in Tombstone had on hand 200,000 feet of lumber suitable for mining, building materials, seasoned flooring, rustic shingles, etc. The sawmill shut down in early November 1882 (AWC, 1882). Morse returned to San Diego and by September 1887 was worth $250,000 in lumber and real estate (TE, 1887).

William Downing erected a substantial sawmill in December 1879 in Pinery Canyon in the Chiricahua Mountains 20 miles south of Fort Bowie (ADS, 1880a,e; AS, 1879a,b; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 100-101; Patt, 2013). The mill began working in January 1880, with many orders already on hand. It supplied lumber to Tombstone for buildings and mines and shipped considerable wood to Tucson (ADS, 1891; Matheny, 1975 p. 37-38). The Cochise County delinquent tax rolls for the year ending 1887 showed that Downing had delinquent taxes of $37.41 on property valued at $1125 (TWE, 1888). The property included a ranch in Pinery Canyon, improvements to the ranch, a sawmill, a house in Dos Cabezas, and miscellaneous items such as harnesses and tools.

In the spring of 1888 Downing moved the sawmill higher up within the Chiricahua Mountains to an area where he believed there was enough timber to run his mill for several years (ADS, 1888). The sawmill temporarily closed in the summer of 1889 when the Copper Queen Company briefly reduced its operations and was using very little lumber (ASB, 1889). A fire of unknown origin destroyed the sawmill and 30,000 feet of lumber in mid July 1891 (ADS, 1891; TWE, 1891a). Downing immediately rebuilt the mill.

In approximately 1895 Downing sold his mill to the Riggs Bros. & Co. (Bailey and Chaput, 2000b, 82-83; Patt, 2013; Potter, 1902; Wilson, 1995, p. 211). The many members of the Riggs family were developing a large cattle operation along the eastern flanks of the Chiricahua Mountains and collectively in time owned approximately 100,000 acres of patented land, controlled about 25,000 acres under forest reserve permits, and held about 50,000 acres by leases. The family operated the former Downing mill in Pine Canyon and later moved it higher within the canyon and then to Barfoot Park, approximately 7.5 miles west of Portal (1994 Chiricahua Peak topographic map 31109-E1-TM-100). The mill eventually logged most of the Barfoot region (Russell, 1982, p. 69-94). Brannick Riggs, Jr. estimated in 1902 that the forest near the mill would supply 4 million board feet of lumber. In 1903 he contracted to supply the Detroit Copper Company at Morenci with 600,000 feet of lumber that would be hauled 15 miles to the Rodella station of the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and then shipped to the company by rail (BDR, 1903; CS, 1903).

Edward F. Sweeney of the Duluth & Chiricahua Development Company bought the Riggs mill in May 1904 for $8000 along with related items such as adjacent track, cars, horses, a logging truck and wagon, and the right to harvest and sell timber from the Chiricahua Forest Reserve under a contract with the federal government (Patt, 2013). The new sawmill company was alternatively called the Sweeney Lumber Company and the Chiricahua Lumber Mills Company. The sawmill supplied lumber to the nearby developing mining town of Paradise and to the Paradise Mining District in the Chiricahua Mountains (BDR, 1904; BDR, 19005; BDR, 1906a,b; GNIS, 2018; TWE, 1906).

In June 1906, the company sold out to Boyer and Sanders with the sale including the mill machinery and all buildings on the ground, all the cut and cured lumber, all wood left over from earlier timber logging, and the right to all standing timber near the mill and in Rustlers’ Park. The new firm announced plans to fill a contract with a mine at Pearce for 2,000,000 feet of mining timber produced at the rate of 50,000 to 60,000 feet per month and to supply mining timber and other lumber to anyone who wished to buy it. In the spring of 1907, the sawmill was removed from Barfoot Park (Pilsbry and Ferriss, 1910).

The sawmill of Daniel Ross harvested thousands of feet of lumber from the Chiricahua Mountains during the 1880s and early 1890s (ASB, 1889; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 92; AWE, 1890; Douglas, 1906, p. 27; Patt, 2013; DT, 1886d; TDE, 1886a,b; TDP, 1890; TWE, 1891c). In 1883 Daniel D. Ross and Jacob Scheerer partnered to buy a sawmill in either John Long or Mormon Canyon. Scheerer sold his share of the facility to Ross in 1886, and the latter subsequently moved the mill into Rock Canyon. After the mill gained the Copper Queen Company as its major customer, it sent most of its output to Bisbee for the company. Most of the timbers wanted by the Copper Queen were 12 x 12 and 10 x 10 in thickness. The mill in April 1890 was cutting 15,000 feet of timber per day and hauling it to Bisbee. The Copper Queen Company was taking all the native lumber it could obtain and importing a significant amount from Oregon. However, the company then preferred local timber because managers believed it was tougher and would stand more severe strains.

In April and May of 1886 and in July 1890 the mill advertised for heavy teams for hauling lumber from it to Bisbee. In the summer of 1889, the sawmill temporarily closed because the Copper Queen Company had momentarily reduced its operations and was using little lumber. The Ross Mill in November 1891 was running full time and producing about 20,000 feet of lumber per day, all of which went to Bisbee. The mill shut down in March 1894 because Ross concluded that it was impossible to make a profit because of the expenses of defending against a federal lawsuit.

During at least the latter part of 1886 Holmes & Thompson sold lumber from their mill at the head of Morse’s Canyon in the Chiricahua Mountains (DT, 1886a,b,e).

The Copper Queen Company and other Bisbee mines first harvested timber from the Mule Mountains (AWC, 1893; Douglas, 1906, p. 27; Douglas, 1910, p. 429, 496 abs.; Schwantes, 2000, p. 90; TWE, 1891b; USDA, 2003, p. 16). However, these mountains were relatively low in elevation compared to the other mountains in southeastern Arizona and supplied only limited amounts of what Douglas termed “stunted wood.”

By the end of the 1880s the Mule Mountains’ supply of lumber suitable for construction was mostly exhausted and could no longer meet the needs of the Bisbee mines. The Copper Queen switched in the middle 1880s to obtaining construction timbers from the Ross mill. Because of the legal expenses incurred in defending itself against a federal civil suit resulting from the purchase of Ross lumber, the Copper Queen Company in 1892 began looking elsewhere for suitable lumber. It found that it could obtain Oregon pine delivered to Benson or Fairbank for $19-$20 per thousand feet versus $32 per thousand feet for lumber from the Chiricahua Mountains delivered in Bisbee. The Southern Pacific imported the timber through San Pedro, California and transported it to Benson.

For several years, the inadequate supply of cut lumber was a limiting factor on the erection of buildings and the development of mines in southeastern Arizona. There was a great scarcity of lumber in Tucson in the latter part of 1879 (PH, 1879). Thirty-four buildings, mostly business houses, were under contract in Tombstone, but builders were waiting for the arrival of lumber so that they could construct the buildings. The Arizona Citizen noted on November 8, 1879 (AC, 1879e) that a dispute among the workers at a sawmill resulted in a shortage of lumber that hampered operations of the Contention Mill. The demand for lumber during 1880 was so great that sawmills could not meet the demands of Tombstone based mining companies (WAC, 1880c).

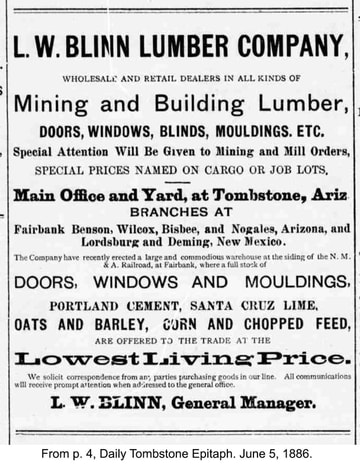

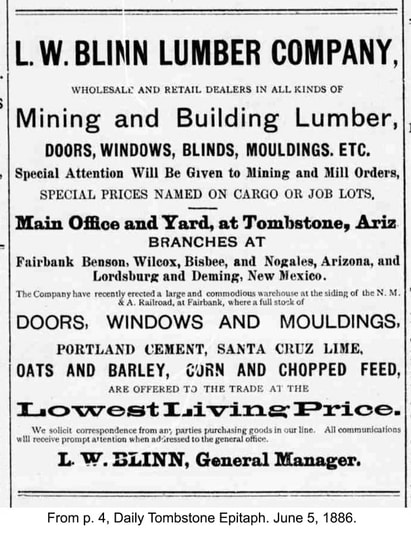

Construction lumber ad

Construction lumber ad

The prominent merchant Lewis Blinn noted the demand for lumber and in May 1880 established a 185 by 210-foot sized lumberyard in Tombstone and by 1885 also had yards elsewhere (AQI, 1881; Bailey and Chaput, 2000a, p. 31; DT, 1886c). He initially sold lumber from the Chiricahua and Huachuca mountains at $60 to $65 per thousand feet. However, he found such lumber unsatisfactory for building purposes because it warped and twisted and therefore switched to selling only seasoned lumber from California.

Blinn was a major provider of lumber by the summer of 1885 and felt secure enough to threaten a rival who offered lower prices. On July 11, 1885 he wrote from Tombstone to Messrs. O. S. Merrill & Co. at Saw Mill, Carr Canyon to expresses outrage that the latter firm had offered to supply Mr. Warrington with lumber for a livery stable at the price of $35 per thousand feet. Blinn wrote, “I can be very disagreeable, and make things very uncomfortable.” He further threatened that “[I]f you supply one single foot of lumber into Tombstone market at any such rates as those proposed, or in any way enter into direct competition with me here, I will see that you cannot make enough out of your lumber to pay the freight.”

The arrival of railroads in the San Pedro River Valley facilitated importation of construction wood from outside Arizona. Even before the Southern Pacific reached Tucson, the A. D. Otis & Company in Tucson in addition to supplying timber from the Chiricahua Mountains was importing in October 1879 large cargoes by rail from California via the Casa Grande railroad terminus and then by wagon to Tucson (ADS, 1879b). The Arizona Daily Star noted on June 10, 1894 that lumber brought by railroad to Fairbank cost $25 per thousand feet, $5 more than lumber transported from the Ross Mill to Bisbee (ADS, 1894). The paper opined that the latter lumber was better suited for mine timber but was not yielding a profit for the Ross Mill because of the legal cost the company was incurring defending itself against the United States government. A future article will discuss the federal lawsuit, government attempts to protect forests, and the harvesting of fuelwood.

References Cited

AC. 1878. Southern Arizona Wood and Timber, p. 1. The Arizona Citizen. October 26, 1878. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39803430).

AC. 1879a. From Thursday’s Daily, p. 3. Arizona citizen. April 18, 1879. (PDF accessed May 31, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-04-18/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

AC. 1879b. Local Matters, p. 3. Arizona Citizen. July 25, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39797151/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1879c. Mining News, p. 2. Arizona Citizen. January 18, 1879. (PDF accessed May 28, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-01-18/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

AC. 1879d. Notice, To-Days, Untitled Article, & The Chiricahua Lumber Mills, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Friday, August 15, 1879. (PDF accessed June 17, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-15/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879e. New Saw-Mill, p. 4. Arizona Citizen. May 23, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-05-23/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

AC. 1879f. Saw-Mill for Chiricahuas, p. 3. Arizona Citizen. June 6, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39796337/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1879g. Tombstone Notes, p. 1. The Arizona Citizen. November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AC. 1879h. Tombstone, p. 1. Arizona Citizen. February 28, 1879. (PDF accessed May 28, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-02-28/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AC. 1879i. Tombstone Notes, p. 1. & Notice of Final Proof, p. 4. The Arizona Citizen, Saturday, November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed August 6, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-1/).

AC. 1879j. Untitled article & To Lumbermen and Teamsters [ad], p. 2. Arizona Citizen. August 8, 1879. (PDF accessed March 26, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-08/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

AC. 1879k. Untitled article, p. 1. Arizona Citizen. May 16, 1879. (PDF accessed May 29, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39795961/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1880. Local Matters, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. January 24, 1880. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1880-01-24/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

ADS. 1879a. Harshaw Happenings, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. September 27, 1879. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1879b. The Lumber Market & Tombstone Mining Notes, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. October 24, 1879. (JPG accessed April 5, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1879c. Tombstone News & Tucson & Tombstone Stage Line. Fare reduced to $7.00, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. October 12, 1879. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162753114/?terms=Mormon+sawmill+Huachuca)

ADS. 1879d. Chiricahua Saw Mill [ad], p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. July 25, 1879. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162710626/?terms=Chiricahua).

ADS. 1880a. Chiricahua and Mule Pass, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 20, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162801842/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1880b. Chiricahua Saw-mill, From the Epitaph & Chiricahua Saw-Mill Morse & Co [ad], p. 1. Arizona Daily Star. May 25, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162684657/?terms=1,000,000+feet+of+lumber).

ADS. 1880c. Huachuca’s Wealth, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 6, 1880. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1880d. Ramsey’s Canyon, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. June 18, 1880. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1880e. Untitled article, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 24, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162803370/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1885. Nogales, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. February 17, 1885. (JPG accessed April 2, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1888. The Day’s News in Brief, p. 6. Arizona Daily Star. March 29, 1888. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162807284/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1891. Territorial News, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. July 26, 1891. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162903394/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1894. Territorial News, From the Prospector, p. 4. Arizona daily Star. June 10, 1894. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/163044047/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).

AQI. 1880. Ramsey’s Cañon in the Huachucas, p. 4. Arizona Quarterly Illustrated. July.

AQI. 1881. Blinn’s Lumber Yard, p. 23. Arizona Quarterly Illustrated. January 1881.

AS. 1878. Untitled article, p. 3. Arizona Sentinel. November 16, 1878. (PDF accessed August 4, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42268826/?terms=Sawmill%2BHuachuca).

AS. 1879a. From the Weekly Nugget, p. 2. Arizona Sentinel. December 13, 1879. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42270387/?terms=Downing).

AS. 1879b. From the Weekly Nugget, p. 2. Arizona Sentinel. November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

ASB. 1889. Territorial Topics, p. 1. Arizona Silver Belt. July 13, 1889. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42147799/?terms=Downing).

AWC. 1880. Local Matters, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Citizen. January 3, 1880. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39785118/?terms=Chiricahua).

AWC. 1882. Territorial Cribbings, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. October 29, 1882. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-10-29/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AWC. 1893. A famous case. The Ross Timber Cutting Matter In a Way for Early Trial, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. June 10, 1893. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1893-06-10/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AWE. 1890. Untitled article, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. April 5, 1890. (PDF accessed September 7, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-04-05/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

Bahre, C. J. 1991. A Legacy of Change: Historic Human Impact on Vegetation in the Arizona Borderlands. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. xviii + 231 p.

Bahre, C. J. and Hutchinson, C. F. 1985. The impact of historic fuelwood cutting on the semidesert woodlands of southeastern Arizona. Journal of Forest History, 29: 175-186.

Bailey, L. R. 2004. Tombstone, Arizona. “Too Tough to Die” the Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Silver Camp: 1878 to 1990. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xiv+398 p.

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000a. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume One: A-K. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xi + 249 p.

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000b. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume Two: L-Z. Westernlore Press, Tucson. 246 p.

Barnes, W. C. 1988. Arizona Place Names. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 503 p.

BDR. 1903. Will Help Rodello Lumber and Mines. Brannick Riggs Sells Lumber to Detroit Copper Co., p. 4. Bisbee Daily Review. March 27, 1903. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024827/1903-03-27/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

BDR. 1904. Paradise Camp Continues Active, p. 3. Bisbee Daily Review. November 15, 1904. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40686938/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1905. Paradise Camp Is Making Headway, p. 4. Bisbee Daily Review. December 21, 1905. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40689238/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1906a. Narrow Escape, p. 9. Bisbee Daily Review. April 29, 1906. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40682922/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1906b. E. F. Sweeney Lumber Company Disposed of to Boyer and Sanders, p. 2. Bisbee Daily Review. June 28, 1906. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40685324/?terms=%22Sweeney%2BLumber%22).

Bennett, C. E. February 11, 1865. Lieutenant Colonel, First Cavalry California Volunteers, Commander Fort Bowie. Letter to Colonel J. C. McFerran, Chief Quartermaster Department of New Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, p. 1134- 1135. In, Davis, G. W., Perry, L. J. and Kirkley, J. W. 1897b. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Published Under the Direction of the Hon. Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War. Series I – Volume L – In two Parts. Part II – Correspondence, Orders and Returns Relating to Operations on the Pacific Coast from July 1, 1862 to June 30, 1865. Government Printing Office, Washington. 1389 p. (PDF accessed June 3, 2015 at https://books.google.com/books?id=dQEVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=davis+1897+part+II+The+War+of+the+Rebellion:+a+Compilation+of+the+Official+Records+of+the+Union+and+Confederate+Armies&source=bl&ots=kwHp4sGHkX&sig=xNBC-L2Qc4SP2JBHUB7bFlZ009w&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TetxVdnaBI-rogTV-IP4Cg&ved=0CDkQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=davis%201897%20part%20II%20The%20War%20of%20the%20Rebellion%3A%20a%20Compilation%20of%20the%20Official%20Records%20of%20the%20Union%20and%20Confederate%20Armies&f=false).

CS. 1903. Untitled article, p. 7. Coconino sun. April 4, 1903. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062055/1903-04-04/ed-1/seq-7.pdf).

Douglas, J. 1906. [1995 reprint.] Notes the Development of Phelps, Dodge & Co.’s Copper and Railroad Interests. Frontera House Press, Bisbee. 35 p.

Douglas, J. 1910. Conservation of natural resources. Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers, 40: 419-431, 486-498. (PDF accessed July 28, 2013 at http://books.google.com/books/download/Transactions_of_the_American_Institute_o.pdf?id=3aBfAAAAMAAJ&hl=en&capid=AFLRE73jcgYPYB9mITLj9XSnbSqLRLdOr1w1ueAzFNjKSpITqsTqW40XBeaoeFhozitD4xN4hZ8a01E-MZovZ6BoF72n37jNhQ&continue=http://books.google.com/books/download/Transactions_of_the_American_Institute_o.pdf%3Fid%3D3aBfAAAAMAAJ%26output%3Dpdf%26hl%3Den).

DT. 1886a. Attention Ranchmen! [Ad], p. 2. The Daily Tombstone. October 30, 1886. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-30/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

DT. 1886b. Attention Ranchmen! [Ad], p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. November 22, 1886. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-11-22/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886c. Blinn the Monopolist, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. October 21, 1886. (PDF accessed March 27, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-21/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886d. Wedding Bells. Mr. Jacob Shearer and Miss Jennie Smith United in the Holy Bonds of Matrimony, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. October 12, 1886. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-12/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886e. Attention Ranchmen [ad], p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. November 24, 1886. (PDF accessed February 18, 2019 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-11-24/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

Farish, T. E. 1916. History of Arizona. Vol. IV. The Filmer Brothers Electrotype Company, San Francisco. ix + 351 p. (PDF accessed August 1, 2013 at http://archive.org/details/historyofarizona04fari).

Fulton, R. W. 1966. Millville-Charleston, Cochise County 1878-1889. The Journal of Arizona History, Spring 1966:9-22.

Garner vs. Gird 1885. Testimony of WM. K. Gird, p 149-153. In Rose, 2013. San Pedro River Water Wars in the Post Drew’s Station Era. John Rose Historical Publications, Sierra Vista, Arizona. xii +346 p.

GNIS. 2018. The Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). The Federal and national standard for geographic nomenclature. (Database at http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic).

Kellog, R. S. 1902. Forest Conditions in Southern Arizona. Forestry and Irrigation, 8 (12): 501-505. (PDF accessed July 8, 2014 at http://books.google.com/books?id=ImwmAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA503&lpg=PA503&dq=%22bull+pine%22+southern+arizona&source=bl&ots=d1HvqLuihD&sig=Yvh9tMjn98ueQMXuqy63qfon_x8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=13S8U56iFZL0oATY_YDoDw&ved=0CEcQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=%22bull%20pine%22%20southern%20arizona&f=false).

Lage, P. L. 1949. History of Fort Huachuca, 1877-1913. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History and Political Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in The Graduate College, University of Arizona. 117 p. (PDF accessed June 17, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553764).

LAH. 1878. For Tombstone District, p. 3. Los Angeles Herald. December 1, 1878. (PDF accessed June 9, 2015 at http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH18790220.2.16&srpos=47&e=01-01-1877-01-01-1907--en-Logical-50--1-byDA--txIN-Tombstone).

LAT. 1896. A Mining Commune. Strange Settlement in The Mountains of Arizona, p. 12. The Los Angeles Times. March 27, 1896. (PDF accessed October 7, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/380173962).

Matheny, R. L. 1975. The History of Lumbering in Arizona before World War II. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Graduate College. The University of Arizona. 393 p. (PDF accessed January 29, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565344).

McClintock, J. H. 1921. Mormon Settlement in Arizona: A Record of Peaceful Conquest of the Desert. (Google eBook). The Manufacturing Stationers Inc., Phoenix. 310 p. (PDF accessed June 16, 2013 at http://books.google.com/books?id=WrkUAAAAYAAJ&dq=Standage+The+march+of+the+Mormon+Battalion&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s).

Meketa, C. & Meketa, J. 1980. One Blanket and Ten Days Rations. 1st Infantry New Mexico Volunteers in Arizona 1864-1866. Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Globe, Arizona. vii + 99 p.

MSP. 1881. Tombstone District. The Mines and Prospects & Wages and Cost of Living in Arizona. Mining and Scientific Press. An Illustrated Journal of Mining, Popular Science and General News, December 17, 1881, 43 (25), p. 404, 412 (PDF accessed August 28, 2014 at https://archive.org/details/miningscien43unse).

O’Leary, D. 1877. Letter from Dan O’Leary. Weekly Arizona Miner, Supplement. Friday, August 10, 1877, p. 5. (PDF downloaded July 21, 2014 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014897/1877-08-10/ed-1/).

Patt, J. 2013. Early Sawmills of the Chiricahuas. The Cochise County Historical Journal, 43 (2): 29-41.

Peterson, B. A. 1999. Sky Islands Righteousness Above the Desert of Sin: “Donnellite” Seeds in Sunnyside Canyon. [PDF based on April 23, 1999 paper presented at Arizona Historical Society Conference, Prescott, AZ.] 28 p. (PDF accessed October 5, 2018 at http://www.mesacc.edu/~bruwn09481/voicewld/Sky-Island-Righteousness.pdf).

PH. 1879. Territorial Items, p. 2. The Phoenix Herald. October 11, 1879. (PDF accessed March 26, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062082/1879-10-11/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

Pilsbry, H. A. and Ferriss, J. H. 1910. Mollusca of the Southwestern States: IV. The Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 62: 44-147. [Footnote 23, p. 113.] (PDF accessed December 16, 2018 at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/28143#page/121/mode/1up).

Potter, A.F. 1902. Map of the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona. File 3428, Entry 918 (National Forest Files – Coronado National Forest), Division R (Forestry), Record Group 49 (Records of the Bureau of Land Management), National Archives, Washington, D.C. [Map reproduced on page 47 in Desert Plants, Vol. 11 (4) December 1995, 2 pages after and of Bahre, 1995. PDF of Vol. 11 accessed June 6, 2018 at https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/553075].

Rose, J. D. 2012. Charleston & Millville, A. T., Hell on the San Pedro. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. xviii + 330 p.

Russell, R. P., Jr. 1982. The History of Man’s Influence upon the Vegetation of the Chiricahua Mountain Meadows. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Geography and Regional Development in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in The Graduate College. The University of Arizona. 188 p. (PDF accessed June 20, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/274681).

Sanderlin, W. S. and Erskine, M. H. 1964. A Cattle Drive from Texas to California: The Diary of M. H. Erskine, 1854. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 67: 397-412.

Schwantes, C. A. 2000. Vision & Enterprise. Exploring the History of Phelps Dodge Corporation. The University of Arizona Press & Phelps Dodge Corporation. xxxii + 464 p.

SFWG. 1864. Report of Scout after Indians, by Capt. T. T. Tidball, p. 2. Santa Fe Weekly Gazette. October 15, 1864. (PDF accessed October 16, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022168/1864-10-15/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

Smith, C. C. 1981. Fort Huachuca The Story of a Frontier Post. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC. Xvi + 417 p. (PDF accessed on May 24, 2018 at https://ia800409.us.archive.org/30/items/forthuachucathes00wash/forthuachucathes00wash.pdf).

Spencer, J. S. 1966. Arizona’s Forests. U. S. Forest Service Resource Bulletin INT-6. 64 p. (PDF accessed May 24, 2018 at https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/ogden/pdfs/historic_pubs/arizona66.pdf).

Spring, J. and Gustafson, A. M. 1966. John Spring’s Arizona. Edited by A. M. Gustafson. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 326 p.

TDE. 1886a. For Sale & Wanted, p. 3. Tombstone Daily Epitaph. May 1, 1886. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39806878/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).

TDE. 1886b. Wanted, p. 3. Tombstone Daily Epitaph. April 30, 1886. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39806855/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).

TDE. 1889. Local Happenings & The Report of the Committee from Cochise County to the Senate Committee on Arid Lands, p. 3. Tombstone Daily Epitaph. September 7, 1889. (PDF accessed July 1, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn96060681/1889-09-07/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

TDP. 1890. Wanted [ad], p. 4. Tombstone Daily Prospector. July 21, 1890. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060902/1890-07-21/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

TE. 1887. Bradshaw’s Stage Line, Local Happenings & Whereabouts of Old Tombstoners, p. 3. Tombstone Epitaph. September 3, 1887. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1887-09-03/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

TWE. 1882. The New Waterworks, p. 1. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. July 15, 1882. (PDF accessed August 7, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42334385/?terms=Gird).

TWE. 1888. Delinquent List, p. 1. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. January 28, 1888. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42333666/?terms=Downing).

TWE. 1891a. Untitled article, p. 6. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. July 19, 1891. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42343727/?terms=Downing).

TWE. 1891b. Untitled article, p. 7. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. June 21, 1891. (PDF accessed June 23, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42342921/?terms=%22Timber+cutting%22).

TWE. 1891c. Untitled article, p. 8. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. November 15, 1891. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42347010/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).

TWE. 1906. Records of Cochise County Instruments Filed with the County Recorder, p. 3. Tombstone Weekly Epitaph. July 8, 1906. (PDF accessed October 25, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42333371/?terms=Huachuca%2Bforest).

Underhill, L. E. (ed.) 1979. The Tombstone Discovery: The recollections of Ed Schieffelin & Richard Gird. Arizona and the West, 21 (1): 37-76.

USDA. 2003. Soil Survey of Cochise County, Arizona Douglas-Tombstone Part. United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service. 733 p. (PDF accessed July 15, 2014 at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MANUSCRIPTS/arizona/AZ671/0/cochise.pdf).

WAC. 1880a. 200,000 Feet of Lumber [ad], p. 2. Weekly Arizona Citizen. July 10, 1880. (PDF accessed May 31, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016240/1880-07-10/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

WAC. 1880b. Territorial News & Untitled article, p. 4. Weekly Arizona Citizen. August 7, 1880. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016240/1880-08-07/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

WAC. 1880c. Tombstone & Territorial News, p. 2. Weekly Arizona Citizen. July 24, 1880. (PDF accessed September 21, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016240/1880-07-24/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

Wilson, J. P. 1995. Islands in the Desert. A History of the Uplands of Southeastern Arizona. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Xxii + 362 p.

Blinn was a major provider of lumber by the summer of 1885 and felt secure enough to threaten a rival who offered lower prices. On July 11, 1885 he wrote from Tombstone to Messrs. O. S. Merrill & Co. at Saw Mill, Carr Canyon to expresses outrage that the latter firm had offered to supply Mr. Warrington with lumber for a livery stable at the price of $35 per thousand feet. Blinn wrote, “I can be very disagreeable, and make things very uncomfortable.” He further threatened that “[I]f you supply one single foot of lumber into Tombstone market at any such rates as those proposed, or in any way enter into direct competition with me here, I will see that you cannot make enough out of your lumber to pay the freight.”

The arrival of railroads in the San Pedro River Valley facilitated importation of construction wood from outside Arizona. Even before the Southern Pacific reached Tucson, the A. D. Otis & Company in Tucson in addition to supplying timber from the Chiricahua Mountains was importing in October 1879 large cargoes by rail from California via the Casa Grande railroad terminus and then by wagon to Tucson (ADS, 1879b). The Arizona Daily Star noted on June 10, 1894 that lumber brought by railroad to Fairbank cost $25 per thousand feet, $5 more than lumber transported from the Ross Mill to Bisbee (ADS, 1894). The paper opined that the latter lumber was better suited for mine timber but was not yielding a profit for the Ross Mill because of the legal cost the company was incurring defending itself against the United States government. A future article will discuss the federal lawsuit, government attempts to protect forests, and the harvesting of fuelwood.

References Cited

AC. 1878. Southern Arizona Wood and Timber, p. 1. The Arizona Citizen. October 26, 1878. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39803430).

AC. 1879a. From Thursday’s Daily, p. 3. Arizona citizen. April 18, 1879. (PDF accessed May 31, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-04-18/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

AC. 1879b. Local Matters, p. 3. Arizona Citizen. July 25, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39797151/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1879c. Mining News, p. 2. Arizona Citizen. January 18, 1879. (PDF accessed May 28, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-01-18/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

AC. 1879d. Notice, To-Days, Untitled Article, & The Chiricahua Lumber Mills, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen, p. 3. Friday, August 15, 1879. (PDF accessed June 17, 2015 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-15/ed-1/seq-3/).

AC. 1879e. New Saw-Mill, p. 4. Arizona Citizen. May 23, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-05-23/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

AC. 1879f. Saw-Mill for Chiricahuas, p. 3. Arizona Citizen. June 6, 1879. (PDF accessed May 30, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39796337/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1879g. Tombstone Notes, p. 1. The Arizona Citizen. November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AC. 1879h. Tombstone, p. 1. Arizona Citizen. February 28, 1879. (PDF accessed May 28, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-02-28/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AC. 1879i. Tombstone Notes, p. 1. & Notice of Final Proof, p. 4. The Arizona Citizen, Saturday, November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed August 6, 2014 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-1/).

AC. 1879j. Untitled article & To Lumbermen and Teamsters [ad], p. 2. Arizona Citizen. August 8, 1879. (PDF accessed March 26, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1879-08-08/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

AC. 1879k. Untitled article, p. 1. Arizona Citizen. May 16, 1879. (PDF accessed May 29, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39795961/?terms=Sawmill).

AC. 1880. Local Matters, p. 3. The Arizona Citizen. January 24, 1880. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014896/1880-01-24/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

ADS. 1879a. Harshaw Happenings, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. September 27, 1879. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1879b. The Lumber Market & Tombstone Mining Notes, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. October 24, 1879. (JPG accessed April 5, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1879c. Tombstone News & Tucson & Tombstone Stage Line. Fare reduced to $7.00, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. October 12, 1879. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162753114/?terms=Mormon+sawmill+Huachuca)

ADS. 1879d. Chiricahua Saw Mill [ad], p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. July 25, 1879. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162710626/?terms=Chiricahua).

ADS. 1880a. Chiricahua and Mule Pass, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 20, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162801842/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1880b. Chiricahua Saw-mill, From the Epitaph & Chiricahua Saw-Mill Morse & Co [ad], p. 1. Arizona Daily Star. May 25, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162684657/?terms=1,000,000+feet+of+lumber).

ADS. 1880c. Huachuca’s Wealth, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 6, 1880. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1880d. Ramsey’s Canyon, p. 3. Arizona Daily Star. June 18, 1880. (JPG accessed March 24, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1880e. Untitled article, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. January 24, 1880. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162803370/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1885. Nogales, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. February 17, 1885. (JPG accessed April 2, 2018 at newspapers.com).

ADS. 1888. The Day’s News in Brief, p. 6. Arizona Daily Star. March 29, 1888. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162807284/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1891. Territorial News, p. 4. Arizona Daily Star. July 26, 1891. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/162903394/?terms=Downing).

ADS. 1894. Territorial News, From the Prospector, p. 4. Arizona daily Star. June 10, 1894. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/163044047/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).

AQI. 1880. Ramsey’s Cañon in the Huachucas, p. 4. Arizona Quarterly Illustrated. July.

AQI. 1881. Blinn’s Lumber Yard, p. 23. Arizona Quarterly Illustrated. January 1881.

AS. 1878. Untitled article, p. 3. Arizona Sentinel. November 16, 1878. (PDF accessed August 4, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42268826/?terms=Sawmill%2BHuachuca).

AS. 1879a. From the Weekly Nugget, p. 2. Arizona Sentinel. December 13, 1879. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42270387/?terms=Downing).

AS. 1879b. From the Weekly Nugget, p. 2. Arizona Sentinel. November 8, 1879. (PDF accessed October 2, 2017 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021912/1879-11-08/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

ASB. 1889. Territorial Topics, p. 1. Arizona Silver Belt. July 13, 1889. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/42147799/?terms=Downing).

AWC. 1880. Local Matters, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Citizen. January 3, 1880. (PDF accessed February 23, 2019 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39785118/?terms=Chiricahua).

AWC. 1882. Territorial Cribbings, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. October 29, 1882. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1882-10-29/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AWC. 1893. A famous case. The Ross Timber Cutting Matter In a Way for Early Trial, p. 1. Arizona Weekly Citizen. June 10, 1893. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1893-06-10/ed-1/seq-1.pdf).

AWE. 1890. Untitled article, p. 3. Arizona Weekly Enterprise. April 5, 1890. (PDF accessed September 7, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052364/1890-04-05/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

Bahre, C. J. 1991. A Legacy of Change: Historic Human Impact on Vegetation in the Arizona Borderlands. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. xviii + 231 p.

Bahre, C. J. and Hutchinson, C. F. 1985. The impact of historic fuelwood cutting on the semidesert woodlands of southeastern Arizona. Journal of Forest History, 29: 175-186.

Bailey, L. R. 2004. Tombstone, Arizona. “Too Tough to Die” the Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Silver Camp: 1878 to 1990. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xiv+398 p.

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000a. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume One: A-K. Westernlore Press, Tucson. xi + 249 p.

Bailey, L. R. and Chaput, D. 2000b. Cochise County Stalwarts. A Who’s Who of the Territorial Years. Volume Two: L-Z. Westernlore Press, Tucson. 246 p.

Barnes, W. C. 1988. Arizona Place Names. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 503 p.

BDR. 1903. Will Help Rodello Lumber and Mines. Brannick Riggs Sells Lumber to Detroit Copper Co., p. 4. Bisbee Daily Review. March 27, 1903. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024827/1903-03-27/ed-1/seq-4.pdf).

BDR. 1904. Paradise Camp Continues Active, p. 3. Bisbee Daily Review. November 15, 1904. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40686938/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1905. Paradise Camp Is Making Headway, p. 4. Bisbee Daily Review. December 21, 1905. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40689238/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1906a. Narrow Escape, p. 9. Bisbee Daily Review. April 29, 1906. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40682922/?terms=Sweeney%2BChiricahua).

BDR. 1906b. E. F. Sweeney Lumber Company Disposed of to Boyer and Sanders, p. 2. Bisbee Daily Review. June 28, 1906. (PDF accessed October 10, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/40685324/?terms=%22Sweeney%2BLumber%22).

Bennett, C. E. February 11, 1865. Lieutenant Colonel, First Cavalry California Volunteers, Commander Fort Bowie. Letter to Colonel J. C. McFerran, Chief Quartermaster Department of New Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, p. 1134- 1135. In, Davis, G. W., Perry, L. J. and Kirkley, J. W. 1897b. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Published Under the Direction of the Hon. Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War. Series I – Volume L – In two Parts. Part II – Correspondence, Orders and Returns Relating to Operations on the Pacific Coast from July 1, 1862 to June 30, 1865. Government Printing Office, Washington. 1389 p. (PDF accessed June 3, 2015 at https://books.google.com/books?id=dQEVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=davis+1897+part+II+The+War+of+the+Rebellion:+a+Compilation+of+the+Official+Records+of+the+Union+and+Confederate+Armies&source=bl&ots=kwHp4sGHkX&sig=xNBC-L2Qc4SP2JBHUB7bFlZ009w&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TetxVdnaBI-rogTV-IP4Cg&ved=0CDkQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=davis%201897%20part%20II%20The%20War%20of%20the%20Rebellion%3A%20a%20Compilation%20of%20the%20Official%20Records%20of%20the%20Union%20and%20Confederate%20Armies&f=false).

CS. 1903. Untitled article, p. 7. Coconino sun. April 4, 1903. (PDF accessed June 6, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062055/1903-04-04/ed-1/seq-7.pdf).

Douglas, J. 1906. [1995 reprint.] Notes the Development of Phelps, Dodge & Co.’s Copper and Railroad Interests. Frontera House Press, Bisbee. 35 p.

Douglas, J. 1910. Conservation of natural resources. Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers, 40: 419-431, 486-498. (PDF accessed July 28, 2013 at http://books.google.com/books/download/Transactions_of_the_American_Institute_o.pdf?id=3aBfAAAAMAAJ&hl=en&capid=AFLRE73jcgYPYB9mITLj9XSnbSqLRLdOr1w1ueAzFNjKSpITqsTqW40XBeaoeFhozitD4xN4hZ8a01E-MZovZ6BoF72n37jNhQ&continue=http://books.google.com/books/download/Transactions_of_the_American_Institute_o.pdf%3Fid%3D3aBfAAAAMAAJ%26output%3Dpdf%26hl%3Den).

DT. 1886a. Attention Ranchmen! [Ad], p. 2. The Daily Tombstone. October 30, 1886. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-30/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

DT. 1886b. Attention Ranchmen! [Ad], p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. November 22, 1886. (PDF accessed June 5, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-11-22/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886c. Blinn the Monopolist, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. October 21, 1886. (PDF accessed March 27, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-21/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886d. Wedding Bells. Mr. Jacob Shearer and Miss Jennie Smith United in the Holy Bonds of Matrimony, p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. October 12, 1886. (PDF accessed June 2, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-10-12/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

DT. 1886e. Attention Ranchmen [ad], p. 3. The Daily Tombstone. November 24, 1886. (PDF accessed February 18, 2019 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94052361/1886-11-24/ed-1/seq-3.pdf).

Farish, T. E. 1916. History of Arizona. Vol. IV. The Filmer Brothers Electrotype Company, San Francisco. ix + 351 p. (PDF accessed August 1, 2013 at http://archive.org/details/historyofarizona04fari).

Fulton, R. W. 1966. Millville-Charleston, Cochise County 1878-1889. The Journal of Arizona History, Spring 1966:9-22.

Garner vs. Gird 1885. Testimony of WM. K. Gird, p 149-153. In Rose, 2013. San Pedro River Water Wars in the Post Drew’s Station Era. John Rose Historical Publications, Sierra Vista, Arizona. xii +346 p.

GNIS. 2018. The Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). The Federal and national standard for geographic nomenclature. (Database at http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic).

Kellog, R. S. 1902. Forest Conditions in Southern Arizona. Forestry and Irrigation, 8 (12): 501-505. (PDF accessed July 8, 2014 at http://books.google.com/books?id=ImwmAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA503&lpg=PA503&dq=%22bull+pine%22+southern+arizona&source=bl&ots=d1HvqLuihD&sig=Yvh9tMjn98ueQMXuqy63qfon_x8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=13S8U56iFZL0oATY_YDoDw&ved=0CEcQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=%22bull%20pine%22%20southern%20arizona&f=false).

Lage, P. L. 1949. History of Fort Huachuca, 1877-1913. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History and Political Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in The Graduate College, University of Arizona. 117 p. (PDF accessed June 17, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553764).

LAH. 1878. For Tombstone District, p. 3. Los Angeles Herald. December 1, 1878. (PDF accessed June 9, 2015 at http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH18790220.2.16&srpos=47&e=01-01-1877-01-01-1907--en-Logical-50--1-byDA--txIN-Tombstone).

LAT. 1896. A Mining Commune. Strange Settlement in The Mountains of Arizona, p. 12. The Los Angeles Times. March 27, 1896. (PDF accessed October 7, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/380173962).

Matheny, R. L. 1975. The History of Lumbering in Arizona before World War II. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Graduate College. The University of Arizona. 393 p. (PDF accessed January 29, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565344).

McClintock, J. H. 1921. Mormon Settlement in Arizona: A Record of Peaceful Conquest of the Desert. (Google eBook). The Manufacturing Stationers Inc., Phoenix. 310 p. (PDF accessed June 16, 2013 at http://books.google.com/books?id=WrkUAAAAYAAJ&dq=Standage+The+march+of+the+Mormon+Battalion&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s).

Meketa, C. & Meketa, J. 1980. One Blanket and Ten Days Rations. 1st Infantry New Mexico Volunteers in Arizona 1864-1866. Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Globe, Arizona. vii + 99 p.

MSP. 1881. Tombstone District. The Mines and Prospects & Wages and Cost of Living in Arizona. Mining and Scientific Press. An Illustrated Journal of Mining, Popular Science and General News, December 17, 1881, 43 (25), p. 404, 412 (PDF accessed August 28, 2014 at https://archive.org/details/miningscien43unse).

O’Leary, D. 1877. Letter from Dan O’Leary. Weekly Arizona Miner, Supplement. Friday, August 10, 1877, p. 5. (PDF downloaded July 21, 2014 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014897/1877-08-10/ed-1/).

Patt, J. 2013. Early Sawmills of the Chiricahuas. The Cochise County Historical Journal, 43 (2): 29-41.

Peterson, B. A. 1999. Sky Islands Righteousness Above the Desert of Sin: “Donnellite” Seeds in Sunnyside Canyon. [PDF based on April 23, 1999 paper presented at Arizona Historical Society Conference, Prescott, AZ.] 28 p. (PDF accessed October 5, 2018 at http://www.mesacc.edu/~bruwn09481/voicewld/Sky-Island-Righteousness.pdf).

PH. 1879. Territorial Items, p. 2. The Phoenix Herald. October 11, 1879. (PDF accessed March 26, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062082/1879-10-11/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

Pilsbry, H. A. and Ferriss, J. H. 1910. Mollusca of the Southwestern States: IV. The Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 62: 44-147. [Footnote 23, p. 113.] (PDF accessed December 16, 2018 at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/28143#page/121/mode/1up).

Potter, A.F. 1902. Map of the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona. File 3428, Entry 918 (National Forest Files – Coronado National Forest), Division R (Forestry), Record Group 49 (Records of the Bureau of Land Management), National Archives, Washington, D.C. [Map reproduced on page 47 in Desert Plants, Vol. 11 (4) December 1995, 2 pages after and of Bahre, 1995. PDF of Vol. 11 accessed June 6, 2018 at https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/553075].

Rose, J. D. 2012. Charleston & Millville, A. T., Hell on the San Pedro. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. xviii + 330 p.

Russell, R. P., Jr. 1982. The History of Man’s Influence upon the Vegetation of the Chiricahua Mountain Meadows. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Geography and Regional Development in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in The Graduate College. The University of Arizona. 188 p. (PDF accessed June 20, 2018 at http://hdl.handle.net/10150/274681).

Sanderlin, W. S. and Erskine, M. H. 1964. A Cattle Drive from Texas to California: The Diary of M. H. Erskine, 1854. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 67: 397-412.

Schwantes, C. A. 2000. Vision & Enterprise. Exploring the History of Phelps Dodge Corporation. The University of Arizona Press & Phelps Dodge Corporation. xxxii + 464 p.

SFWG. 1864. Report of Scout after Indians, by Capt. T. T. Tidball, p. 2. Santa Fe Weekly Gazette. October 15, 1864. (PDF accessed October 16, 2018 at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022168/1864-10-15/ed-1/seq-2.pdf).

Smith, C. C. 1981. Fort Huachuca The Story of a Frontier Post. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC. Xvi + 417 p. (PDF accessed on May 24, 2018 at https://ia800409.us.archive.org/30/items/forthuachucathes00wash/forthuachucathes00wash.pdf).

Spencer, J. S. 1966. Arizona’s Forests. U. S. Forest Service Resource Bulletin INT-6. 64 p. (PDF accessed May 24, 2018 at https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/ogden/pdfs/historic_pubs/arizona66.pdf).

Spring, J. and Gustafson, A. M. 1966. John Spring’s Arizona. Edited by A. M. Gustafson. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 326 p.

TDE. 1886a. For Sale & Wanted, p. 3. Tombstone Daily Epitaph. May 1, 1886. (PDF accessed June 3, 2018 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/39806878/?terms=Ross+Chiricahua).